Entrenched in tradition, Inuit men grapple with widening Sarah Boesveld

advertisement

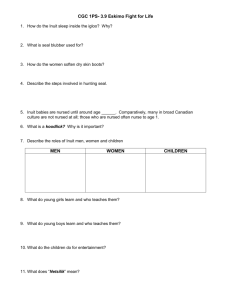

Entrenched in tradition, Inuit men grapple with widening gender gap in Nunavut’s workforce Sarah Boesveld | Dec 11, 2012 7:03 PM ET | Last Updated: Dec 11, 2012 7:05 PM ET More from Sarah Boesveld | @sarahboesveld Cole Burston for the National Post While girls sit down, focus, and study in school, boys haven’t been graduating at the same levels, said Noel Kaludjak, one of the researchers with the Nunavut Literacy Council-run Northern Men’s Research Project, which is gathered in Ottawa this week to plan the early stages of its three-year pan-northern study to kick off in January. Inuit women outnumber Inuit men in Nunavut public service jobs almost three to one, the widening gender gap in the territory’s workforce spurring researchers to study what’s keeping men out of the formal economy and out of post-secondary education. The rest of Canada, like the rest of the world, has also seen women increasingly graduate post-secondary schools and enter the well-paid workforce at a higher rate, but the scenario is magnified in the North — a region where bureaucracy is new and the culturally entrenched seal, polar bear and caribou hunts now have far less market value. Traditional male-female roles are still very entrenched in Inuit culture, experts say, and in many ways men are still the providers as they head out on the hunt every spring when the seals are calving and bring food home for their families. But that hunt doesn’t pay the bills the way administrative jobs — the ones filling newspaper classified sections and filled by women — do. To get those jobs, one needs an education. While girls sit down, focus, and study, boys haven’t been graduating at the same levels, said Noel Kaludjak, one of the researchers with the Nunavut Literacy Council-run Northern Men’s Research Project, which is gathered in Ottawa this week to plan the early stages of its three-year pan-northern study to kick off in January. Girls are also more likely to leave home to find a job, he said. In his work as a counsellor running a men’s group in Coral Harbour, Mr. Kaladjuk has heard from men dissatisfied by the new reality — grappling with abuse issues, largely stemming from their own fathers, and meeting barrier after barrier when it comes to finding work. “We’re not trying to put man higher up than woman, we’re just trying to help them be as they’re supposed to be,” he said from Ottawa on Tuesday. According to Nunavut government statistics, 1,1191 Inuit women worked in the public service in March, 2011. In the same month, only 377 Inuit men filled such jobs — the numbers quite likely affected by the timing of the hunt. Unemployment is also rampant (hunting and gathering doesn’t count as employment), Mr. Kaludjak said, and when a person’s on social assistance, rent can go up when a paycheque arrives. A once nomadic people has become sedentary in recent decades, and this sedentary work may be better geared towards soft skills passed down from generation to generation amongst Inuit women, said Terry Audla, president of Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami, the national organization representing Inuit people. “Inuit men have always played a large role in providing for the family but the dynamics of it have definitely shifted,” he said. “He was the hunter, going out on the land, preparing the equipment and the dog team … whereas the woman stayed home and put together everything the family needed for clothing. And to a certain degree that would be a little bit more static as opposed to the man going out every day to try and gather and harvest the seal, caribou or the polar bear.” In this way, the new “non-Inuit lifestyle” of having to stay indoors and work is “more in tune” with women, he said. Men are still under pressure to go out and hunt, Mr. Audla said, “and if you don’t do well in school, what alternatives do you have?” There’s a need for balance, so men can work at paying jobs that use their traditional skills and go off to hunt during the spring season. Related After officers shot at eight times in six years, RCMP double size of Kimmirut detachment No sign of Nunavut mayor who’s been missing since November But the education system is getting better at addressing the way Inuit boys learn, said Pujjuut Kusaguk, a former high school teacher and the current mayor of Rankin Inlet. The Arctic College Trade School has opened up and will take on male students who learn in a more hands-on way, amid hopes of an expanded mining industry. Meanwhile, the territory’s education department is also embarking on a community-based study called the Young Men’s Engagement Initiative to find out how to re-engage young men in their education. The surveying will also begin in January. The department’s director of assessment and evaluation Donald Mearns says they’ve already started introducing “land programs” that teach hunting and small engine repair. “It’s about making males think of jobs and work in a different way,” he said. “Jobs and work that were predominately male orientated – the mechanic, hunter, fisher, gatherer — those are things guys are still very interested in because, as I say, there are very few men who have made their way into office work and school work and things like that.”