Evaluation: Rebuild by Design Phase I n tio da

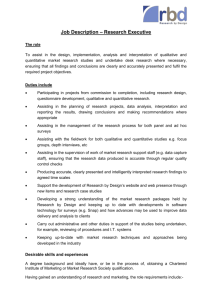

advertisement