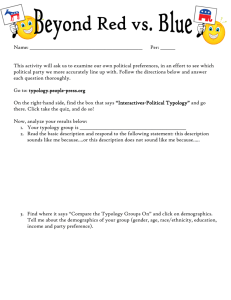

A Typology of Payment Methods Payment Methods and Benefit Designs:

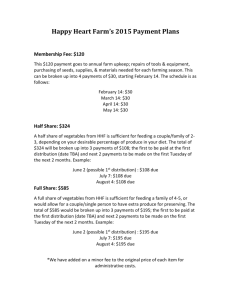

advertisement