CONTRIBUTIONS OF A BABYFACE AND A CHILDLIKE VOICE TO IMPRESSIONS OF

advertisement

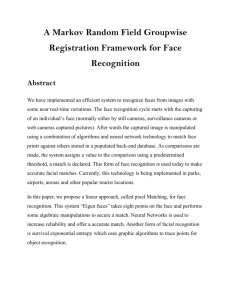

CONTRIBUTIONS OF A BABYFACE AND A CHILDLIKE VOICE TO IMPRESSIONS OF MOVING AND TALKING FACES Leslie Zebrowitz-McArthur Joann M. Montepare ABSTRACT: The present research examined if the impact of a babyface on trait im- pressions documented in previous research holds true for moving faces. It also assessed the relative impact of a babyface and a childlike voice on impressions of talking faces. To achieve these goals, male and female targets' traits as well as their facial and vocal characteristics were rated in one of four information conditions: Static Face, Moving Face, Voice Only, or Talking Face. Facial structure measurements were also made by two independent judges. Data for male faces supported the experimental hypotheses. Specifically, regression analyses revealed that although a babyish facial structure created the impression of weakness even when a target moved his face, this effect was diminished when he also talked. Here a childlike voice and dynamic babyishness, as assessed by moving face ratings, were more important predictors. Similarly, a babyish facial structure had less impact on impressions of a talking target's warmth than did dynamic babyishness or other facial movement. A childlike voice had no impact on impressions of warmth when facial information was available. Researchers in nonverbal person perception have long recognized that perceptions of people's traits are strongly tied to their physical attributes. However, there have been few successful attempts at identifying what specific attributes create particular trait impressions and why they do so (Knapp, 1980). Recent research concerning the effects of facial babyishness has begun to address these questions. More specifically, it has demonstrated that adults with facial structures that ethologists identify as babyish are perceived to have more childlike psychological traits than those This research was supported by a NIMH Grant #BSR 5 R01 MH42684 to the first author. The authors would like to thank Linda Linn for her assistance in preparing the stimulus materials and Danylle Rudin for her help in collecting the data. Thanks are also extended to David M. Buss for his suggestions about alternative explanations which may' help guide future work. Address reprint requests to: Leslie Zebrowitz-McArthur, Department of Psychology, Brandeis University, Waltham, MA 02254. Journal of Nonverbal Behavior 13(3), Fall 1989 © 1989 Human Sciences Press 189 1 90 J OURNAL OF NONVERBAL BEHAVIOR with a more mature appearance. For example, McArthur and Apatow (1983-84) manipulated the babyishness of facial features in young adult schematic faces and found that larger eyes, shorter features, and lower vertical placement of features, which yields a larger forehead and a smaller chin, each increased perceivers' impressions of a target's weakness, sub missiveness, and naivete. Impressions of people depicted in photographs have yielded similar results (Berry & McArthur, 1985; Keating, 1985; McArthur & Berry, 1987). Large, round eyes, high eyebrows, a narrow chin, and a soft, as opposed to angular, face each yielded a babyish facial appearance. Moreover, these features, as we!! as rated babyfacedness, increased perceivers' impressions of people's weakness, submissiveness, naivete, honesty, and warmth. A childlike voice, like a babyface, also has been shown to create impressions of childlike psychological traits. Young adult speakers with vocal qualities perceived as childlike—high pitched, unclear, and tight voices —were perceived as weaker, less competent, and warmer when they recited the English alphabet than were their more mature sounding counterparts (Montepare & Zebrowitz-McArthur, 1 987). Research on impressions created by babyish physical attributes is grounded in an ecological theory of social perception (McArthur & Baron, 1983). This theory holds that such facia! and vocal characteristics provide accurate and useful knowledge to all social perceivers about the behavioral affordances of the young, which are the opportunities for acting or being acted upon that babies provide. For example, not only are babies differentiated from adults by their unique facial characteristics, but also these babyish features yield accurate impressions of their relative weakness and dependency (see Berry & McArthur, 1 986, for a review of relevant research). Such reactions are adaptive for species survival insofar as they serve to insure that the young are provided with the care, protection; and guidance they require to survive. The ecological theory further holds that because it is so important for members of our species to perceive affordances communicated by a baby's physical attributes, these affordances may be overdetected by perceivers in adults whose facial or vocal qualities resemble those of the young. Thus, the documented perceptions of adults with babyfaces or childlike voices may be viewed as an overgeneralization of adaptive reactions to the facial configuration and vocal qualities of real children. Research conducted within the ecological framework has done much to promote an understanding of associations between specific physical attributes and trait impressions. However, theoretically important questions remain unanswered. One issue concerns the generalizability of babyfaced- LESLIE ZEBROWITZ-McARTHUR, JOANN M. MONTEPARE ness effects to dynamic faces. Although the schematic and photographed faces used in previous research made it possible to manipulate and identify potential sources of stimulus information, the information that these faces provide, is very impoverished. The question thus remains as to whether or not the impact on impressions of a babyish facial structure is retained for animated faces, which may provide trait information unavailable in static displays. Given that perceptions of attributes such as personal identity are retained when a person's face moves, one might expect that perceptions of a person's traits will also remain intact. On the other hand, it is also possible that impressions created by as of yet unidentified facial movement information will attentuate the effects derived from static structural qualities. Another question of theoretical interest is whether the impact on impressions of childlike face or voice persists when information from the other channel is available to perceivers. Questions regarding the relative impact of facial and vocal cues on person perception have long been of interest (Allport & Vernon, 1967; Wolff, 1943). However, the methods used in systematic research on this topic have focused on the relative impact of the two channels without respect to the specific facial and vocal cues that are exerting an effect. What the multichannel research has established is that facial information often outweighs vocal information, although this 'visual primacy' effect varies with the attribute being judged (Fridlund, Ekman, & Oster, 1 987). For example, O'Sullivan, Ekman, Friesen, and Scherer (1985) have found that the visual primacy effect does not obtain for judgments of dominance for which voice and face have equal effects. To extend our understanding of the impact of physical attributes on impression formation, the present study addressed two questions: 1) Do the babyfacedness effects documented in past research hold true for dynamic faces; and 2) What is the relative impact of a babyface and a childlike voice on perceptions of people's traits when both facial and vocal information are available to perceivers. To answer these questions, subjects rated the traits and physical characteristics of adult targets presented in one of four information conditions: Static Face, Moving Face, Voice Alone, Talking Face. Method Subjects Sixty-four male and 64 female U.S. undergraduates enrolled in an introductory Psychology course participated for experimental credit. An equal number of men and women were randomly assigned to one of four stimulus information condi- 1 92 JOURNAL OF NONVERBAL BEHAVIOR tions; one of two target sex conditions; one of two orders of presentation of the targets; and one of two orders of dependent measures. Stimulus Information Conditions Targets were presented to subjects in one of four different stimulus conditions. The Static Face Condition consisted of still, head and shoulder color slides of 14 men aged 21-36 and 16 women, aged 19-37. None of the targets had glasses, facial hair, or other distinctive qualities of appearance.' The remaining three conditions were created by videorecording the targets as they recited the alphabet for approximately 25 seconds while walking back and forth the length of a room.' The Moving Face Condition consisted of silent color videotapes depicting the head and shoulders of the target persons. The Voice Alone Condition consisted of the soundtrack from these videotapes. The Talking Face Condition was identical to the Mov ing Face condition except that the videotapes were played with the sound track. Dependent Measures Trait characteristics. Subjects rated targets on 7-point bipolar trait scales reflecting characteristics that had been influenced by babyfacedness and a childlike voice in past research. These were submissive/dominating, physically weak/physically strong, vulnerable/invulnerable, naive/wise, warm/cold, and straightforward/deceitful. Face and voice characteristics. Subjects in the Static and the Moving Face conditions rated the targets' facial structure on nine 7-point bipolar scales that are theoretically related to babyfacedness: low/high eyebrows; small/large eyes; closeset/wide set eyes; narrow/broad chin; short/long chin; small/large nose; small/large forehead; curved/angular jaw; and smooth/rough skin. Subjects in the Moving and the Talking Face Conditions rated the targets' facial movements on six 7-point bipolar scales tapping the degree to which they moved their eyes, blinked their eyes, showed their teeth, moved their heads, smiled, and were animated. These movements were selected because they were easily identifiable and were similar to ratings used by researchers studying judgments of affect (Knapp, 1980). Finally, subjects in the Voice Alone and the Talking Face conditions rated the targets' voices on six, 7-point bipolar scales representing characteristics proposed to carry age information and known to influence trait impressions. These were very high/very deep voice, very soft/very loud voice, relaxed/tight voice, does not speak clearly/speaks clearly, monotone/changing voice, and speaks very slowly/speaks very rapidly. The order of the voice and facial rating scales in the Talking Face condition was counterbalanced across subjects. Facial measurements were made independently by two judges by projecting each face onto a flat wall surface and measuring several characteristics with a ruler to the nearest one sixteenth of an inch (see Figure 1). With the exception of skin smoothness and jaw angularity, which could not be readily measured, the facial 'Sixteen men were originally photographed. However, two were omitted because they looked unshaven in the slides. ' Gait behaviors were also recorded on videotape for another study investigating the impact of gait information on trait impressions. 193 LESLIE ZEBROWITZ-McARTHUR, JOANN M. MONTEPARE measurements paralleled the facial ratings noted above. Two other differences were the measurement of facial roundness and cheekbone prominence, which were not included in the subjective ratings due to time limitations. Following the procedure employed by Cunningham (1986), all measurements were divided either by the length of the face or the width at mouth level in order to correct for any variations in overall face size.' FIGURE 1 Facial Measurements 3 The following facial measures were calculated. Eyesize was the product of (4) eye height (distance between top and bottom of eye at center) and (5) eye width (distance between left and right corner of eye). Eyebrow height was the (3) distance from the pupil center to the eyebrow. Eye separation was the (6) distance between the inner corners of each eye. Chin width was (12) the width at the point halfway between the bottom lip and the base of the chin. Chin length was the (11) distance from the lower lip center to the base of the chin. Forehead height 'was the (2) distance from the middle of the pupil to the top of head minus 1/2 of the hair length. Nose size was the product of (9) nose tip width and (10) nose length (distance from the bridge at the eye center to nose tip). Cheekbone prominence was the (7) distance between the outer edges of the face at the widest part of the cheekbone minus the (8) width of the face at the mouth. Facial roundness was the (8) width of the face at the mouth divided by face length which was the (1) distance from the hairline to the base of the chin. To correct for variations in face size, all vertical measures were divided by face length (1), horizontal measures (5) and (6) were divided by face width (7), and horizontal measures (9) and (12) were divided by face width (8). 194 J OURNAL OF NONVERBAL BEHAVIOR In addition to the measures of specific facial and vocal qualities, subjects rated the targets on 7-point bipolar scales measuring global perceptions of their facial immaturity, vocal immaturity, and facial attractiveness. Subjects also estimated the age, in years, of each target. Procedure Subjects were told that the study concerned how people's physical characteristics influence impressions of them, and that they were to rate several targets on a series of scales. During the testing sessions, subjects sat in a semicircle approximately 1.2 m away from the audio source or visual display. Subjects first completed the trait ratings, then the face or voice ratings, and finally the immaturity, attractiveness, and age ratings. Immaturity and age ratings were made last to reduce potential biases in subjects' trait ratings due to age-stereotypic labeling. Results Data Base Standardized Cronbach's coefficients for subjects' ratings of static, moving, and talking male and female faces were computed to determine interrater reliability. The reliabilities for male faces were uniformly high (M = .81 for the trait ratings, M = .89 for the facial structure ratings, M = .88 for the facial movement ratings, M = .88 for the vocal quality ratings, and M = .85 for the three global ratings). The reliabilities for female faces were high for ratings of physical characteristics (M = .86 for facial structure ratings, M = .96 for facial movement ratings, M = .92 for vocal quality ratings, and M = .90 for three global ratings). The trait ratings for female faces also achieved acceptable levels of reliability in the Voice and in the Talking Face Conditions (Ms = .80 and .79, respectively), and a marginal level of reliability in the Moving Face Condition (M = .72). However, in the Static Face Condition, only 2 out of 6 reliabilities for trait ratings exceeded .70 and 3 ratings were below .60. Because these low reliabilities prevented an adequate test of the experimental hypotheses, subsequent analyses were confined to the data for the male faces.' Having demonstrated acceptable interrater reliability for ratings of male faces, mean ratings for each face were computed across subjects for each dependent measure in each experimental condition. A principle4 An analysis of the data for female faces was attempted using the trait composites described below, as well as the individual ratings of weakness and warmth which did manifest acceptable interrater reliability in the Static Face condition. However, none of these trait ratings was correlated with either rated immaturity or a composite of structural babyfacedness derived for female faces. It was consequently impossible to test the generalizability of Static Face maturity effects to the Moving and Talking Face conditions for female faces. 1 95 LESLIE ZEBROWITZ-McARTHUR, JOANN M. MONTEPARE components factor analysis was then performed on the mean trait ratings in the Static Face condition and revealed two significant factors. The first factor included traits reflecting physical, intellectual, and social weakness and included ratings of physical weakness, vulnerability, naivete, and submissiveness. A weakness composite was computed for each target in each condition by averaging across these four trait ratings. The second factor reflected interpersonal warmth and included ratings of warmth and straightforwardness. A warmth composite was computed for each target by averaging across these two ratings. Physical Predictors of Trait Impressions Structural babyfacedness. The facial measurements were correlated with their respective facial ratings in the Static Face Condition to determine their phenomenological validity. The correlations were significant for all measures (all ps< .05) except for nose area and chin length, and these two measurements were consequently omitted from subsequent analyses. Table 1 presents correlations between facial maturity ratings and the valid facial measurements as well as the subjective ratings that had no measured equivalent (rough skin, angular jaw). The structural features listed in Table 1 were entered as potential predictors into an all possible regressions analysis (Meter, Wasserman, & Kutner, 1985) with facial immaturity ratings in the Static Face Condition as the criterion variable. The best subset of predictors to emerge were a narrow chin, a curved, as opposed to angular, jaw, and close set eyes, which together accounted for 74% of the variance in subjective ratings of facial immaturity, F(3, 10)= 9.25, p = .003. The first two predictor variables were consistent with theoretical expectations as well as with past research findings (Berry & McArthur, 1985). The third predictor—close set eyes— was theoretically related to facial maturity, not immaturity. However, Berry and McArthur (1985) had also found a positive relationship between close set eyes and babyfacedness, albeit at only a marginal level of significance. All three facial structure predictors were incorporated into a composite for use in subsequent analyses by converting their values to z scores and multiplying them by the appropriate standardized regression coefficient. The three weighted values obtained for each face were summed to create a weighted linear composite of the babyishness of each target face. Facial movement. Since Berry (1987) has shown that facial movement influences the perceived age of targets, an effort was made to construct a TABLE 1 Intercorrelations among Predictor Variables Static Face Maturity Rating (SM) Moving Face Maturity Rating (MM) Talking Face Maturity Rating (TM) Structural Babyfacedness (SB) Voice Vocal Maturity Rating (VM) Talking Face Vocal Maturity Rating (TVM) Childlike Voice Composite (CV) Facial Movement (FM) Static Face Attractiveness Rating (SA) Moving Face Attractiveness Rating (MA) Talking Face Attractiveness Rating (TA) s.10 ‡p *p .05 **p < .01 ***p s .001 5- SM MM TM SB VM TVM CV FM SA MA TA - .65** .47‡ .87*** - .86*** - .60* - .46‡ - .10 - .08 - .01 -.19 .10 .31 .44 -.04 .44 - .16 - .06 - .27 -.26 -.78*** - .63* - .36 - .34 -.25 .59* .17 .18 - .26 - .08 - .41 -.48‡ .00 -.09 -.33 .39 .12 .14 - .29 -.16 - .28 .06 -.10 .00 .22 .62* .23 - .20 -.01 - .32 .09 -.04 - .09 - .04 .42 .86*** 197 LESLIE ZEBROWITZ-McARTHUR, JOANN M. MONTEPARE babyish facial movement composite by performing an all possible regressions analysis with the facial movement ratings as predictor variables and rated facial immaturity in the Moving Face Condition as the criterion. However, none of the regression equations was significant, and the correlations between individual facial movements and facial maturity were also non-significant. Therefore, a principle components factor analysis was performed on the facial movement ratings in an attempt to construct a movement measure to use as a predictor of trait impressions. This analysis yielded one significant factor that included moving eyes, showing teeth, moving head, smiling, and being animated. A facial movement composite was constructed by averaging across these five ratings weighted by their respective factor loadings. Childlike voice. The childlike voice composite derived for each target in an earlier study employing the same voices (Montepare and ZebrowitzMcArthur, 1987) was used as a predictor in the present study. This composite was constructed by averaging across the three vocal ratings which predicted perceived vocal childlikeness independently of perceived vocal femininity (higher pitch, greater tightness, and lower clarity). The composite was strongly correlated with the perceived childlikeness of the men's voices, r(14) = .73, p< .001. Attractiveness. Considerable research has shown that facial attractive- ness influences perceivers' impressions of people's traits (e.g., Hatfield & Sprecher, 1986). Therefore, subsequent analyses took into consideration the impact of facial attractiveness on impressions of Static, Moving, and Talking Faces. Mean ratings of facial attractiveness in the Static Face Condition served as the index of structural attractiveness and mean ratings of facial attractiveness in the Moving and Talking Face Conditions served as indices of dynamic attractiveness. The Relative Impact of the Physical Predictors on Trait Impressions Pearson r correlation coefficients showing the relationships among the various physical predictors are presented in Table 2. To determine the relative strength and independence of the effects of the four physical predictors on impressions, the relevant physical measures within each experimental condition were simultaneously entered as predictors of trait ratings in multiple regression analyses. I mpressions of static faces. Structural babyfacedness and structural at- tractiveness served as predictors of trait ratings. Consistent with past re- 198 J OURNAL OF NONVERBAL BEHAVIOR search, babyfacedness independently predicted ratings of weakness and warmth. Attractiveness also emerged as a significant predictor of both traits (see Table 3). Impressions of moving faces. Structural babyfacedness, dynamic attractiveness, and facial movement served as predictors of Moving Face trait ratings. Consistent with the effect for static faces, structural babyfacedness independently predicted ratings of weakness. The best predictor of warmth was facial movement, although neither this effect nor those of the other predictors were significant (see Table 3). It should be noted that the loss of physical attractiveness as a predictor in the Moving Face condition was not due to the use of Moving Face attractiveness, since regression analyses utilizing Static Face attractiveness yielded the same effects. To determine whether the weaker effects of structural babyfacedness were due to a failure to capture the structural features that look immature in a moving face, a structural babyfacedness composite was derived with maturity ratings in the Moving Face condition as the criterion. This composite, comprised of an angular jaw and rough skin, did not predict trait ratings any better than the one based on Static Face maturity ratings. Impressions of voices. In the Voice Alone condition, a childlike voice served as the only predictor of trait ratings. Consistent with previous research, a childlike voice significantly predicted ratings of warmth and weakness, rs(12) = .73 and .72, ps < .005, respectively. TABLE 2 Correlations , between Facial Immaturity Ratings and Facial Measurements Facial Measurement Eyesize Eyebrow height Eye separation Chin width Forehead height Facial roundness Cheekbone prominence Angular jaw Rough skin *p<.10;**p<.05 Immaturity Ratings Static Faces Moving Faces — .48* —.38 —.10 —.13 —.66** -.37 —.28 —.17 .46* .08 .23 .25 —.16 —.01 —.48* —.51** —.33 —.56** Errata In the Zebrowitz-McArthur and Montepare article, "Contributions of a babyface and a childlike voice to impressions of moving and talking faces" (Fall, 1989), several errors were made in the signs of the r values in Table 3 (p. 199) and Table 4 (p. 200). All of the correlations and partial correlations between the trait of Weakness and Static or Dynamic Attractiveness should be negative rather than positive. 199 LESLIE ZEBROWITZ-McARTHUR, JOANN M. MONTEPARE TABLE 3 Multiple Regression Analyses Predicting Trait Ratings Trait Warmth (Static Face) R2 .64 Predictor Structural Babyface Static Attractiveness r partial r t p .55 .62 .65 .72 2.86 3.43 .02 .006 .46 .62 .71 .75 3.35 3.76 .007 .003 .55 .74 .28 ..37 .47 .36 1.25 1.67 1.20 .24 .13 .26 .71 .42 .33 .64 .01 .16 2.65 <1 <1 .03 .61 .45 .26 .64 .38 1.51 <1 2.53 1.24 16 03 25 .45 .61 .35 .51 1.50 2.31 1.13 1.76 .17 .05 .29 .11 F(2,11)=9.97, p<.004 Weakness (Static Face) .70 Structural Babyface Static Attractiveness F(2,11) =12.69, p<.002 Warmth ( Moving Face) .62 Structural Babyface Facial Movement Dynamic Attractiveness F(3,10) = 5.37, p<.02 Weakness (Moving Face) .62 Structural Babyface Facial Movement Dynamic Attractiveness F(3,10)=5.45, p<.02 Warmth , (Talking Face) .69 Structural Babyface Childlike Voice Facial Movement Dynamic Attractiveness .11 .77 .09 F(4,9) = 5.08, p<.02 Weakness (Talking Face) .68 Structural Babyface Childlike Voice Facial Movement Dynamic Attractiveness .47 .33 .40 .55 F(4,9) = 4.69, p<.03 Impressions of talking faces. Structural babyfacedness, dynamic attractiveness, facial movement, and a childlike voice served as predictors of Talking Face trait ratings. Structural babyfacedness failed to predict ratings of either weakness or warmth. Facial movement predicted ratings of warmth, and a childlike voice predicted ratings of weakness (see Table 3). Although structural babyfacedness was not a significant predictor of trait ratings in the Talking Face Condition, it is possible that dynamic aspects of, facial maturity not captured by the structural composite did make 200 JOURNAL OF NONVERBAL BEHAVIOR a significant contribution to impressions. To investigate this possibility, regression analyses were performed on trait ratings of moving and talking faces with rated immaturity of the moving faces and voices as predictors in place of structural babyfacedness and a childlike voice. Unlike structural babyfacedness, rated facia! immaturity predicted perceived weakness and warmth in both the Moving and the Talking Face conditions. On the other hand, rated vocal immaturity was not a better predictor than the childlike voice composite (see Table 4). 5 TABLE 4 Multiple Regression Analyses Using Rated Facial and Vocal Immaturity 6 Trait R2 Warmth .75 (Moving Face) Predictor Facial Immaturity Facia! Movement Dynamic Attractiveness r partial r t p .68 .74 .28 .67 .73 .04 2.82 3.36 <1 .02 .007 .66 .42 .33 .83 .53 .79 4.75 1.97 4.09 .001 .08 .003 .57 .12 .77 .09 .66 .06 .77 .05 2.67 <1 3.64 <1 .03 .54 .29 .40 .55 .60 .48 .42 .72 2.23 1.65 1.38 3.13 .05 .13 .20 .01 F(3,10) = 10.17 p<.003 Weakness .80 (Moving Face) Facial Immaturity Facial Movement Dynamic Attractiveness F(3,10) = 13.49, p<.001 Warmth (Talking Face) .78 Facial Immaturity Vocal Immaturity Facial Movement Dynamic Attractiveness .005 F(4,9) = 7.84, p<.005 Weakness (Talking Face) .70 Facial Immaturity Vocal Immaturity Facial Movement Dynamic Attractiveness F(4,9) = 5.17, p<.02 'To rule out the possibility that the effects of the physical predictors on trait ratings were due to variations in the targets' perceived age, mean ratings of the age of each target in each condition were correlated with the ratings of warmth and weakness. These correlations were not significant, ranging between - .01 and - .34, thereby ruling out the possibility that the observed impressions reflected the application of age stereotypes. 'The effects of rated facial maturity are roughly equivalent whether rated vocal maturity or a childlike voice is entered into the regression analyses with rated facial maturity. 201 LESLIE ZEBROWITZ-McARTHUR, JOANN M. MONTEPARE Discussion The present research demonstrates that the tendency for a childlike face to create impressions of childlike personality traits is retained for dynamic, videotaped faces. Structural babyfacedness independently predicted impressions of the weakness of both photographed and videotaped faces of male targets. On the other hand, it predicted impressions of the warmth of photographed faces, but not videotaped ones. The rated facial immaturity of videotaped faces, which captures their dynamic qualities, and the facial movement composite each emerged as independent predictors of their perceived warmth. The present study also examined the impact of a childlike face on impressions of moving and talking female faces. However, the predicted babyfacedness effects were not found in the Static Face condition thereby precluding subsequent tests of the experimental hypotheses. The failure to find . babyfacedness effects for the female faces in the present study most likely reflects some idiosyncracies of the particular sample of faces which were used. Indeed, a recent study by Berry and Brownlow (1988) utilizing another set of static female faces obtained strong babyfacedness effects suggesting that future research using a different sample of faces will find effects with female faces which parallel those found for male faces in the present study. As argued in the introduction, the effects of structural babyfacedness and rated facial immaturity may be viewed as an overgeneralization of adaptive reactions to the facial qualities of real children. The impact of the facial movement composite, on the other hand, may derive from its accurate diagnosis of the traits comprising the warmth composite. The greater warmth attributed to people who exhibited considerable facial movement may simply reflect the fact that people's faces are indeed more animated and smiling when they are feeling 'warmly' toward another. Similarly, the tendency to perceive people who exhibit considerable facial movement as more 'straightforward', the second trait in the warmth composite, may reflectthe fact that people tend to show less facial movement when they are lying than when they are telling the truth (Zuckerman & Driver, 1 985). Consistent with visual primacy effects demonstrated in past multichannel research, the present study revealed that the face exerted a stronger impact on impressions of warmth than the voice, whereas both face and voice influenced impressions of weakness (e.g., O'Sullivan, et at., 1985). In addition, the present study extended past research findings by identifying specific vocal and facial qualities that influence these impressions. Rated facial babyishness and the facial movement composite 202 J OURNAL OF NONVERBAL BEHAVIOR both predicted the perceived warmth of talking faces, whereas a childlike voice, either rated or measured, did not. On the other hand, vocal as well as facial immaturity predicted the perceived weakness of talking faces. Why does a childlike voice exert a stronger impact on perceptions of a person's weakness than warmth? One possible answer is that vocal characteristics are more accurate indicators of a person's weakness. Supporting this argument is the fact that vocal qualities convey accurate information about a person's height and weight, which may be considered indices of physical power (Lass & Davis, 1976). Vocal qualities may also convey accurate information about a person's social power. For example, Zuckerman, Amidon, Bishop, and Pomerantz (1982) found that subjects' content filtered speech accurately communicated their feelings of dominance and submission. In summary, the present research has been successful in extending our knowledge about the impact of facial and vocal characteristics on social perceptions. The tendency for a childlike face to create impressions of childlike personality traits has been demonstrated for videotaped faces of young adult men. Although the static babyish features contributing to these effects have been identified, it remains for future research to identify the dynamic babyish qualities, since they were independent of the facial movement measures employed in the present study. In addition, when both facial and vocal information are available to the perceiver, a childlike face and voice each contributes to the impression of weakness, but only a childlike face has a significant impact on the impression of warmth. References Allport, G. W., & Vernon, P. E. (1967). Studies in expressive movement. New York: MacMillan. Berry, D. S. (1987). What can a moving face tell us? Unpublished dissertation, Brandeis University. Berry, D. S., & Brownlow, S. (1989). Were the physiognomists right? Personality correlates of facial babyishness. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 15, 266-279. Berry, D. S. & McArthur, L. Z. (1985). Some components and consequences of a babyface. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 48, 312-323. Berry, D. S. & McArthur, L. Z. (1986). Perceiving character in faces: The impact of agerelated craniofacial changes on social perceptions. Psychological Bulletin, 100, 3-18. Cunningham, M. R. (1986). Measuring the physical in physical attractiveness: Quasi-experiments on the sociobiology of female facial beauty. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 50, 925-935. Fridlund, A. J., Ekman, P., & Oster, H. (1987). Facial expression and emotion. In A. W. Siegman & S. Feldstein (Eds.), Nonverbal behavior and communication (pp. 143-224). Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaurn Associates. LESLIE ZEBROWITZ-McARTHUR, JOANN M. MONTEPARE Hatfield, E. & Sprecher, S. (1986). Mirror, mirror . . . The importance of looks in everyday life. Albany, NY: State University of New York Press. Keating, C. F. (1985). Human dominance signals: The primate in us. In S. L. Ellyson & J. F. Dovidio (Eds.), Power, dominance, and nonverbal behavior (pp. 89-109). New York: Springer-Verlag. Knapp, M. L. (1980). Essentials of nonverbal communication. New York: Holt, Rinehart, & Winston. Lass, L. J., & Davis, M. (1976). An investigation of speaker height and weight identification. Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, 60, 700-707. McArthur, L. Z., & Apatow, K. (1983/84). Impressions of baby-faced adults. Social Cognition, 2, 315-342. McArthur, L. Z., & Baron, R. M. (1983). Toward an ecological theory of social perception. Psychological Review, 90, 215-238. McArthur, L. Z., & Berry, D. S. (1987). Cross-cultural agreement in perceptions of babyfaced adults. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 18, 165-192. Montepare, J. M., & Zebrowitz-McArthur, L. (1987). Perceptions of adults with childlike voices in two cultures. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 23, 331-349. Neter, J., Wasserman, W., & Kutner, M. H. (1985). Applied linear statistical models: Regression, analysis of variance, and experimental designs (2nd ed., pp. 421-429). Homewood, IL: Irwin. O'Sullivan, M., Ekman, P., Friesen, W., & Scherer, K. (1985). What you say and how you say it: The contribution of speech content and voice quality to judgments of others. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 48, 54-62. Wolff, W. (1943). The expression of personality. New York: Harper. Zuckerman, M., & Driver, R. E. (1985). Telling lies: Verbal and nonverbal correlates of deception. In A. W. Siegman & S. Feldstein (Eds.), Multichannel integrations of nonverbal behavior (pp. 129-149). Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. Zuckerman, M., Amidom, M. D., Bishop, S. E., & Pomerantz, S. C. (1982). Face and tone of voice in the communication of deception. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 43, 347-357.