The First Thanksgiving (Handout)

advertisement

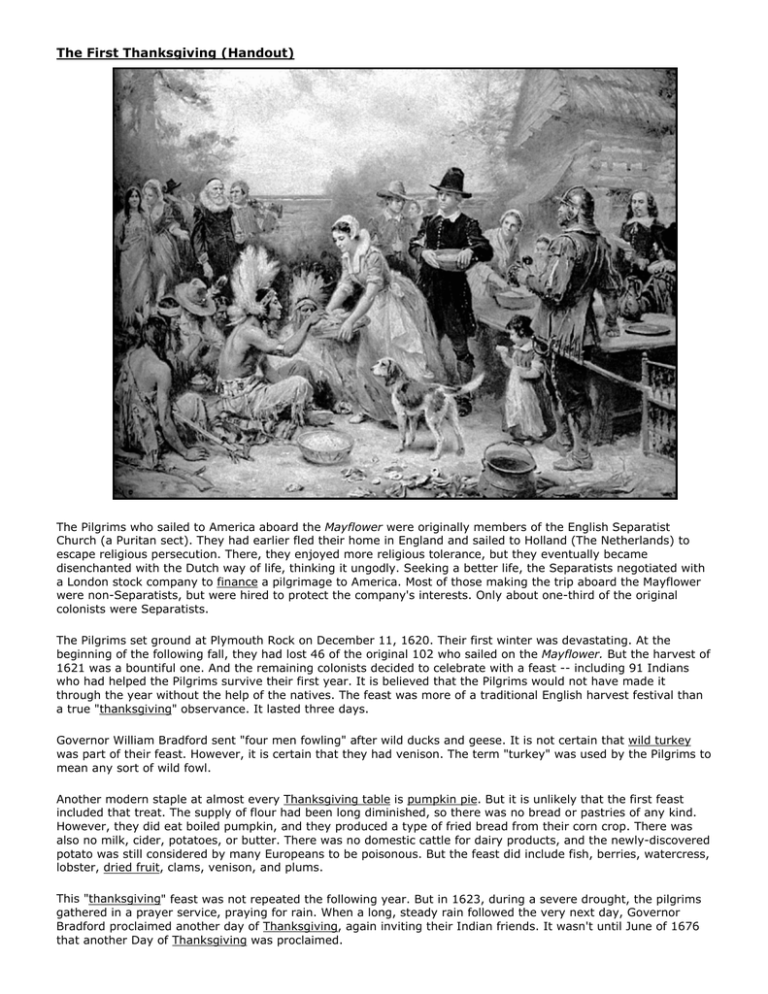

The First Thanksgiving (Handout) The Pilgrims who sailed to America aboard the Mayflower were originally members of the English Separatist Church (a Puritan sect). They had earlier fled their home in England and sailed to Holland (The Netherlands) to escape religious persecution. There, they enjoyed more religious tolerance, but they eventually became disenchanted with the Dutch way of life, thinking it ungodly. Seeking a better life, the Separatists negotiated with a London stock company to finance a pilgrimage to America. Most of those making the trip aboard the Mayflower were non-Separatists, but were hired to protect the company's interests. Only about one-third of the original colonists were Separatists. The Pilgrims set ground at Plymouth Rock on December 11, 1620. Their first winter was devastating. At the beginning of the following fall, they had lost 46 of the original 102 who sailed on the Mayflower. But the harvest of 1621 was a bountiful one. And the remaining colonists decided to celebrate with a feast -- including 91 Indians who had helped the Pilgrims survive their first year. It is believed that the Pilgrims would not have made it through the year without the help of the natives. The feast was more of a traditional English harvest festival than a true "thanksgiving" observance. It lasted three days. Governor William Bradford sent "four men fowling" after wild ducks and geese. It is not certain that wild turkey was part of their feast. However, it is certain that they had venison. The term "turkey" was used by the Pilgrims to mean any sort of wild fowl. Another modern staple at almost every Thanksgiving table is pumpkin pie. But it is unlikely that the first feast included that treat. The supply of flour had been long diminished, so there was no bread or pastries of any kind. However, they did eat boiled pumpkin, and they produced a type of fried bread from their corn crop. There was also no milk, cider, potatoes, or butter. There was no domestic cattle for dairy products, and the newly-discovered potato was still considered by many Europeans to be poisonous. But the feast did include fish, berries, watercress, lobster, dried fruit, clams, venison, and plums. This "thanksgiving" feast was not repeated the following year. But in 1623, during a severe drought, the pilgrims gathered in a prayer service, praying for rain. When a long, steady rain followed the very next day, Governor Bradford proclaimed another day of Thanksgiving, again inviting their Indian friends. It wasn't until June of 1676 that another Day of Thanksgiving was proclaimed. On June 20, 1676, the governing council of Charlestown, Massachusetts, held a meeting to determine how best to express thanks for the good fortune that had seen their community securely established. By unanimous vote they instructed Edward Rawson, the clerk, to proclaim June 29 as a day of thanksgiving. It is notable that this thanksgiving celebration probably did not include the Indians, as the celebration was meant partly to be in recognition of the colonists' recent victory over the "heathen natives," (see the proclamation). October of 1777 marked the first time that all 13 colonies joined in a thanksgiving celebration. It also commemorated the patriotic victory over the British at Saratoga. But it was a one-time affair. George Washington proclaimed a National Day of Thanksgiving in 1789, although some were opposed to it. There was discord among the colonies, many feeling the hardships of a few Pilgrims did not warrant a national holiday. And later, President Thomas Jefferson scoffed at the idea of having a day of thanksgiving. It was Sarah Josepha Hale, a magazine editor, whose efforts eventually led to what we recognize as Thanksgiving. Hale wrote many editorials championing her cause in her Boston Ladies' Magazine, and later, in Godey's Lady's Book. Finally, after a 40-year campaign of writing editorials and letters to governors and presidents, Hale's obsession became a reality when, in 1863, President Lincoln proclaimed the last Thursday in November as a national day of Thanksgiving. Thanksgiving was proclaimed by every president after Lincoln. The date was changed a couple of times, most recently by Franklin Roosevelt, who set it up one week to the next-to-last Thursday in order to create a longer Christmas shopping season. Public uproar against this decision caused the president to move Thanksgiving back to its original date two years later. And in 1941, Thanksgiving was finally sanctioned by Congress as a legal holiday, as the fourth Thursday in November. 1. What year did the Pilgrims have their first Thanksgiving Feast? 2. What food was probably NOT on the Pilgrims' Thanksgiving menu? 3. The Horn of Plenty, or Cornucopia, which symbolizes abundance, originated in what country? 4. In 1676, a day of thanksgiving was proclaimed to take place during what month? 5. What president didn't like the idea of having a national Thanksgiving Day? 6. Who is credited with leading the crusade to establish Thanksgiving Day? 7. Which president first established the date of Thanksgiving as a national celebration? 8. Which president moved the date of Thanksgiving twice? 9. The reason Thanksgiving was moved up a week was... 10. Canada celebrates Thanksgiving on... (The answer is not in the narrative.) The Salem Witch Trials, 1692 (Handout) The seeds of the hysteria that afflicted Salem Village, Massachusetts were sown in January 1692 when a group of young girls began to display bizarre behavior. The tight-knit community was at a loss to explain the convulsive seizures, blasphemous screaming, and trance-like states that afflicted the youngsters. The physicians called in to examine the girls could find no natural cause of the disturbing behavior. If the source of the affliction was not attributable to a physical malady, the community reasoned that it must be the work of Satan. Witches had invaded Salem. In February the village began praying and fasting in order to rid itself of the devil's influence. The girls were pressured to reveal who in the community controlled their behavior. Three women were identified and examined. One, Tituba (a slave), confessed to seeing the devil who appeared to her "sometimes like a hog and sometimes like a great dog." Even more troubling, Tituba confessed that a conspiracy of witches permeated Salem Village. In March the afflicted girls accused Martha Corey. The three women previously denounced as colluding with the devil were marginal to the community. Martha Corey was different; she was an upstanding member of the Puritan congregation - her revelation as a witch demonstrated that Satan's influence reached to the very core of the community. Events snowballed as the accusatory atmosphere intensified and reached a fever pitch. During the period from March into the fall many were charged, examined, tried and condemned to death. The hangings started in June with the death of Bridget Bishop and continued through September. As winter approached, the hysteria played itself out as criticism of the procedures grew. In October, the colonial governor dissolved the local Court of inquiry. The convictions and condemnations for witchery stopped. Nineteen victims of the witch-hunt had been hanged, one crushed to death under the weight of stones and at least four died in prison awaiting trial. The Trial of Martha Corey Friday March 11, 1692 was a day of fasting and prayer in Salem. During the day the community's minister, the Rev. Samuel Parris, asked the girls to reveal another witch. They did, and the accusation shocked those who heard it for it implicated Martha Corey (Goodwife Corey) a new but upstanding member of the congregation. Immediately a delegation was sent to the Corey farm to interview the accused in the hope of clearing up this discrepancy. Martha Corey's sarcastic response to the accusation disheartened the delegation who immediately called for her arrest. Her trial was the scene of much agitation. In the courtroom Martha's accusers writhed in agony as they were forced by an unseen power to mimic the witch's every movement. When Martha shifted her feet the girls did also, when Martha bit her lip the girls were compelled to bit their own lips, crying out in pain. They saw the specter of a black man bending over the accused and heard the drum beat calling the witches to convene on the meetinghouse lawn. Deodat Lawson, a visiting minister, describes the scene: "On, Monday, the 21st. of March, the magistrates of Salem appointed to come to examination of Goodwife Corey. And about twelve of the clock they went into the meeting house, which was thronged with spectators. Mr. Noyes began with a very pertinent and pathetic prayer, and Goodwife Corey being called to answer to what was alleged against her, she desired to go to prayer, which was much wondered at, in the presence of so many hundred people. The magistrates told her they would not admit it; they came not there to hear her pray, but to examine her in what was alleged against her. The worshipful Mr. Hathorne asked her why she afflicted those children. She said she did not afflict them. He asked her, 'Who did then?' She said, 'I do not know; how should I know?' The number of the afflicted persons were about that time ten, viz. four married women: Mrs. Pope, Mrs. Putnam, Goodwife Bibber, and an ancient woman named Goodall; three maids-. Mary Walcut, Mercy Lewes, at Thomas Putnam's, and a maid at Dr. Griggs's; there were three girls from nine to twelve years of age, each of them, or thereabouts, viz. Elizabeth Parris, Abigail Williams, and Ann Putnam. These were most of them at Goodwife Corey's examination, and did vehemently accuse her in the assembly of afflicting them, by biting, pinching, strangling, etc.; and that they did in their fit see her likeness coming to them, and bringing a book to them. She said she had no book. They affirmed she had a yellow bird that used to suck betwixt her fingers; and being asked about it, if the had any familiar spirit that attended her, she said she had no familiarity with any such thing, she was a gospel woman, which title she called herself by. And the afflicted persons told her ah, she was a gospel witch. Ann Putnam did there affirm that one day when Lieutenant Fuller was at prayer at her father's house she saw the shape of Goodwife Corey and she thought Goodwife N, praying at the same time to the Devil. She was not sure it was Goodwife N., she thought it was, but very sure she saw the shape, of Goodwife Corey. The said Corey said they were poor, distracted children, and no heed to be given to what they said. Mr. Hathorne and Mr. Noyes replied it was the judgment of all present they were bewitched, and only she, the accused person, said they were distracted. It was observed several times that if she did but bite her underlip in time of examination, the persons afflicted were bitten on their arms and wrists and produced the marks before the magistrates, ministers, and others. And being watched for that, if she did but pinch her fingers, or grasp one hand hard in another, they were pinched, and produced the marks before the magistrates and spectators. After that, it was observed that if she did but lean her breast against the seat in the meeting house (being the bar at which she stood), they were afflicted. Particularly Mrs. Pope complained of grievous torment in her bowels as if they were, torn out. She vehemently accused said Corey as the instrument, and first threw her muff at her, but that not flying home, she got off her shoe, and hit Goodwife Corey on the head with it. After these postures were watched, if said Corey did but stir her feet, they were afflicted in their feet, and stamped fearfully. The afflicted persons asked her why she did not go to the company of witches which were before the meeting house mustering. Did she not hear the drum beat? They accused her of having familiarity with the Devil, in the time of examination, in the shape of a black man whispering in her ear; they affirmed that her yellow bird sucked betwixt her fingers in the assembly; and, order being given to see if there were any sign, the, girl that saw it said it was too late now; she had removed a pin, and put it on her head, which was found there sticking upright. ... she denied all that was charged upon her, and said they could not prove her a witch. She was that afternoon committed to Salem prison; and after she was in custody, she did not so appear to them and afflict them as before." References: Lawson, Deodat, A Brief and True Narrative of Some Remarkable Passages Relating to Sundry Persons Afflicted by Witchcraft at Salem Village(1692) [reprinted in Commager, Henry Steele, The Heritage of America (1949)]; Starkey, Marion, The Devil in Massachusetts (1989); Trask, Richard, "The Devil Hath Been Risen" (1997).