Denver Supportive Housing Social Impact Bond Initiative Evaluation and Research Design Mary Cunningham

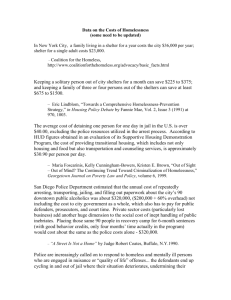

advertisement