Palace and the Dutch Palace, is located in Kochi, a... The mural detail that we will examine here is from

advertisement

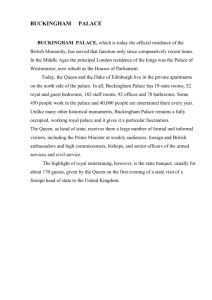

Palace and the Dutch Palace, is located in Kochi, a port city on the western coast of India. Kochi (or Cochin) has a long history in the story of Indian colonialism— in fact, it was the location of the first formal European settlement in India, after the Portuguese arrived there in 1500. The Portuguese were superseded by the Dutch in the mid-seventeenth century, who were in turn followed by the British in the nineteenth. The palace was originally built by the Portuguese as a gift for the Raja of Kochi around 1555.29 The Portuguese had plundered a nearby temple, and the palace was intended as a peace offering. The palace was renovated under the Dutch in 1663, and since that date has been known popularly as the Dutch Palace. The palace’s main architectural significance lies in the fact that it is one of the oldest examples of Portuguese architecture which shows Indian influence in its design and decoration. In this way it is a unique structure. The basic plan of the palace follows a traditional Kerala design—it is a two-story quadrangular structure with long interior halls and a central courtyard space. Within the courtyard sits a temple dedicated to Pazhayannur Bhagavati, the patron goddess of the royal family of Kochi. The upper story of the building includes a coronation hall, a bed chamber, a ladies chamber, and the dining hall. The palace was restored in 1951. At that time it was classified as a centrally protected monument. Recent restoration work has further enhanced and protected the site, which, since 1985, has housed a museum. The museum presents a wide variety of items associated with the royal family, including a series of portraits of the Kochin kings, a group of ornately decorated palanquins and doli (human-powered, wheel-less vehicles used for transporting the nobility), clothing and weaponry, as well as coins and postal stamps issued by the Kochin kings. Detail of a Wall Painting in the Rajah’s Palace: Analysis While the architecture of the palace is notable, and the museum provides a fascinating view of the ruling class of Kochi, the most significant aspect of this site is the murals covering more than three thousand square feet of interior wall space. These mythological murals are considered some of the best in India. The majority of the wall paintings were created when the building was renovated by the Dutch in 1663. They may be found in various rooms throughout the palace and also in the stairwell connecting the first and second stories of the building. Most of the imagery focuses on depictions of Hindu gods and goddesses. Figures such as Shiva, Vishnu, Krishna, and Durga make various appearances. The paintings illustrate various Purana tales, as well as scenes from the Kumarasambhava and other epic poems by the Sanskrit poet Kalidasa. 66 The mural detail that we will examine here is from the series of paintings that decorate the king’s bedchamber, which is placed upstairs at the southwest corner of the palace. The room’s three hundred square feet of wall space are covered with approximately forty-eight individual paintings, all related to the narrative of the Ramayana. These paintings are the oldest in the palace, dating to the seventeenth century. They illustrate the Ramayana epic in its entirety, from the birth of Rama and his brothers to the return of Rama to Ayodhya. In this detail Rama and Lakshmana are entering into an alliance with the monkey king Sugriva. In the poem, Rama and Lakshmana enter the monkey king’s territory. As they bathe in a nearby lake, he watches them anxiously. According to the poem, Sugriva worried “Who could these princes be and why have they come to Rishyamuka Mountain?” Sugriva was seized by fear, thinking that they could be allies of his brother Vali, who was his enemy. “These two princes have been sent by Vali to kill me,” Sugriva told his ministers. “See! Although they are disguised as mendicants, they are carrying bows and arrows.”30 Sugriva sends his attendant Hanuman to meet Rama and Lakshmana. Hanuman brings them to the palace, where they recount their story to the monkey king and ask for his assistance. “Sugriva was overjoyed. He extended his hand in friendship and agreed to help Lord Rama recover Sita.”31 In this very complex scene, we see the figures of Rama, Lakshmana, King Sugriva, and Hanuman. As in the other images in the cycle, Rama is identified by his green skin. He is positioned to the lower left in our image, and he is presented with an expressionless face and narrowed eyes. His serene presence is one of his most important attributes, and we see it here in his generally calm demeanor. He holds an arrow as described in the poem, and he looks across to Sugriva who is made visually (and thus conceptually) prominent by his white skin and reddish brown face. Sugriva and Hanuman (who is seen in the upper left in our image) are depicted with elongated noses and broad upper jaws. These details are intended to show that they are monkey figures. Lakshmana is seen in the center, with bluish-green skin and wide open eyes. The bodies of the figures are very difficult to distinguish, as they overlap and are pressed closely together within the space of the painting. A number of figures and objects surround this central group, adding to the visual complexity and claustrophobic character of the image. The figures wear extremely decorative costumes and elaborate headdresses. We see the rich colors and strongly outlined forms that are typical of Kerala mural painting. The bodies, specifically the details of skin, show the USAD Art Resource Guide • 2015-2016 • Revised Page