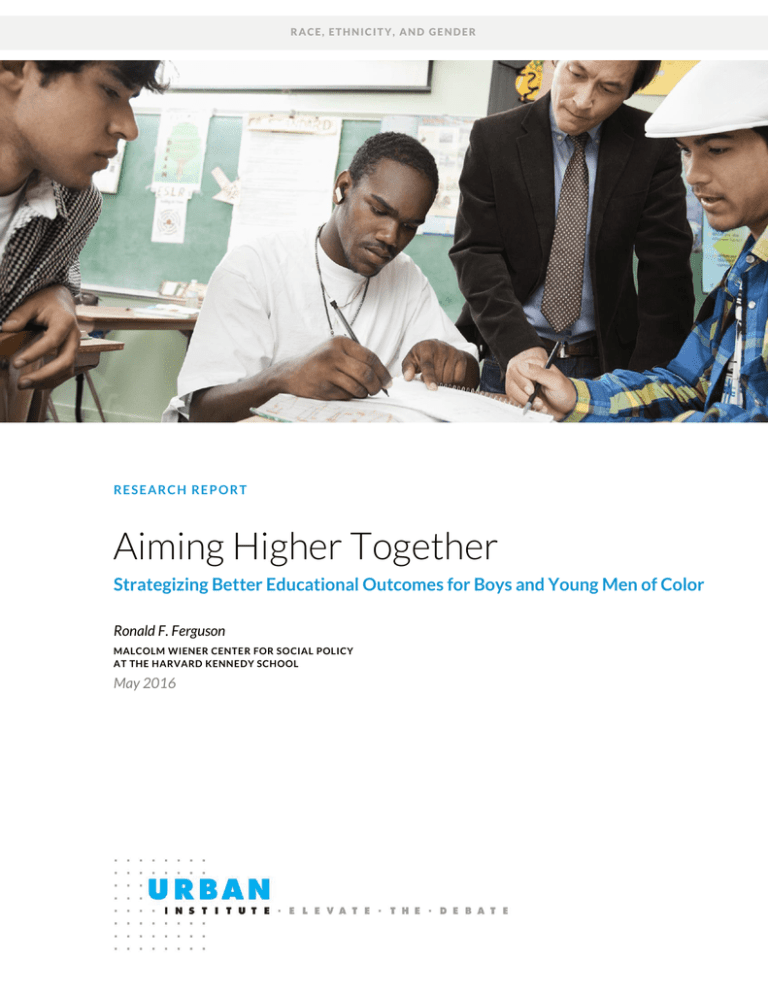

Aiming Higher Together Ronald F. Ferguson

advertisement