e Utilisation and Environmental Protection of Shared International Freshwater

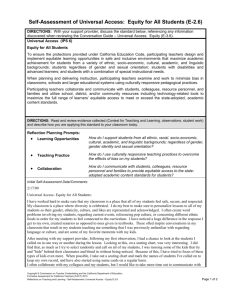

advertisement