Document 14409096

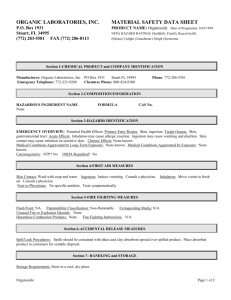

advertisement