Stigma After Exoneration? How Potential Results

advertisement

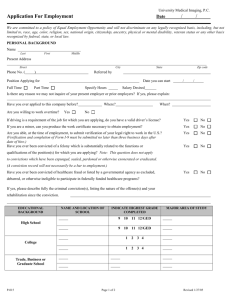

Stigma After Exoneration? How Potential Employers View Those with a Wrongful Conviction Bretton M. Hoekwater and Eric E. Jones, Calvin College Introduction To date, over 320 people have been exonerated through DNA evidence after serving time in prison for a crime they did not commit.1 Over a thousand more have been exonerated through other means.2 Currently, much of the research about wrongful convictions deals with how a person may be wrongfully convicted, such as through mistaken eyewitness identification, a false confession, or other factors (e.g., Clow, Leach, & Ricciardelli, 2011; Jenkins, 2014). Very little research has investigated the challenges after exoneration (e.g., Clow & Leach, 2015). The current research aimed to begin filling this gap. A potential cost of being wrongfully convicted is the stigma associated with being in prison (Clow, Ricciardelli, & Cain, 2012). People are also prone to commit the fundamental attribution error (Ross, 1977). In terms of an exoneree, employers may assume that the wrongful conviction occurred because of the type of person the applicant is. Therefore, we specifically examined how employers evaluated fictitious job candidates, some of whom had spent time in prison for a crime they did not commit. For the reasons stated above, we hypothesized that wrongfully-convicted applicants would be perceived less positively than applicants with no conviction record. Results Except for honesty, all perceptions of the applicants differed as a function of the condition (all Fs > 3.86, all ps < 0.05). For individual deviance and dangerousness, the actual conviction condition was significantly higher than the other conditions. For prospects of advancement, the actual conviction condition was significantly lower than the other conditions. For organizational deviance, the wrongful conviction discovered condition was significantly lower than the other conditions. In terms of honesty, there were no significant differences (see Table 1 below). For hiring decisions, the actual conviction condition was significantly lower than the other conditions. In other words, the participants were less likely to hire the applicant with a conviction (see Figure 2 below). Dependent Variables Individual Deviance Organizational Deviance Dangerousness Prospects of Advancement Honesty Methods Control with No Conviction Actual Conviction Wrongful Conviction Disclosed Wrongful Conviction Discovered 2.26a (1.02) 2.83b (1.26) 2.40ab (1.03) 1.89a (0.93) 2.35a 2.86a 2.46a 1.74b (1.06) (1.23) (1.18) (0.89) 2.85a 4.15b 2.89a 2.78a (1.16) (1.26) (1.10) (1.43) 4.71a 3.56b 4.36a 4.52a (0.93) (1.26) (1.10) (1.30) 4.80a 4.41a 4.85a 4.56a (0.77) (1.12) (0.87) (1.29) Table 1: Means in the same row with different subscripts are significantly different. For this study, 115 participants completed an online experiment. We recruited them using a snowball sampling technique. Participant Demographics: 57% Female, MAge = 46.4 years, 92% Caucasian, and 58% held a managerial position or higher. Each participant reviewed an application and was randomly assigned to one of four conditions, which involved a manipulation of the applicant’s history. The manipulation occurred with how the applicant responded to this question: “Have you ever been convicted of a felony?” (see Figure 1 below). 1. The applicant with no conviction checked the box “No”. 2. The applicant with an actual conviction checked the box “Yes” and explained “I was convicted of robbing a bar at gunpoint and served 3 years in prison until I completed my sentence.” 3. The applicant with a wrongful conviction disclosed checked the box “Yes” and explained “I was convicted of robbing a bar at gunpoint and served 3 years in prison until it was proven that I had not committed the crime.” 4. The applicant with a wrongful conviction discovered through a Google search checked the box “No.” However, participants received information about a Google search that provided similar information about the wrongful conviction as in condition 3. After viewing the application, participants rated the candidate on perceived dangerousness, workplace deviance, prospects for advancement, and honesty. They also stated whether or not they would hire the applicant. Figure 1: Application Figure 2 Discussion and References Our results showed a stigma against those with an actual conviction because they were seen as more dangerous and deviant. They were also less likely to be hired and were perceived as less likely to advance in the company if they were hired. These results did not follow those of Clow and Leach (2015), who found that the wrongfully convicted were liked significantly less than the general population and similar to that of felons. Moreover, in their study, the wrongfully convicted were perceived similarly to convicts and lower than the general public on warmth, friendliness, and respect. Our results could be inconsistent with those of Clow and Leach (2015) because our participants received more information. This individuating information sometimes reduces the likelihood for stereotyping (Häfner & Stapel, 2009). In short, the more information we receive about a particular individual, the less likely we may be to stereotype or show bias against them. However, this concept of individuating information does not seem to impact those with an actual conviction, perhaps because people believe it is okay to show bias against that group. References Clow, K. A., & Leach, A.-M. (2015). After innocence: Perceptions of individuals who have been wrongfully convicted. Legal and Criminological Psychology, 20, 164. Clow, K. A., Leach, A.-M., & Ricciardelli, R. (2011). Life after wrongful conviction. In B. L. Cutler’s (Ed.), Conviction of the innocent: Lessons from psychological research (pp. 327-341). Washington, DC: APA Books. Clow, K. A., Ricciardelli, R., & Cain, T. L. (2012). Stigma-by-association: Prejudicial effects of the prison experience for offenders and exonerees. In D. W. Russell & C. A. Russell’s (Eds.), The psychology of prejudice: Interdisciplinary perspectives on contemporary issues. (pp. 127-154). New York: Nova Science Publishers, Inc. Häfner, M., & Stapel, D. A. (2009). Familiarity can increase (and decrease) stereotyping: Heuristic processing or enhanced knowledge usability? Social Cognition, 27(4), 615-622. 1Innocence Project. (2012). Retrieved from http://www.innocenceproject.org/. Jenkins, S. (2014). Families at war? relationships between ‘survivors’ or wrongful conviction and ‘survivors’ of serious crime. International Review of Victimology, 20(2), 243-261. doi: 10.1177/0269758014521739. 2National Registry of Exonerations. (2015). Retrieved from http://www.law.umich.edu/special/exoneration/Pages/about.aspx. Ross, L. (1977). The intuitive psychologist and his shortcomings: Distortions in the attribution process. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, 10, 173-220.