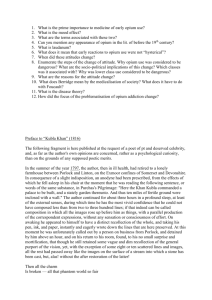

THOMAS DE QUINCEY (1785-1859), born in Manchester the

advertisement