FLUID-BASED ENERGY CONVERSION BY MEANS OF A PIEZOELECTRIC MEMS GENERATOR

advertisement

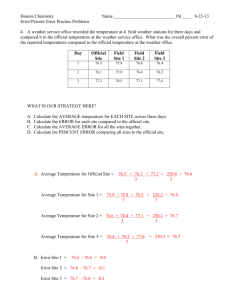

FLUID-BASED ENERGY CONVERSION BY MEANS OF A PIEZOELECTRIC MEMS GENERATOR Ingo Kuehne*, Matthias Schreiter, Julian Seidel and Alexander Frey Siemens AG, Corporate Technology, Corporate Research and Technologies, Munich, Germany *Presenting Author: kuehne.ingo@siemens.com Abstract: This paper reports the optimum design, fabrication and characterization of a piezoelectric MEMS generator for fluid-actuated energy harvesting. Depending on the specific load scenario optimum beam shapes of piezoelectric cantilevers are investigated by theoretical estimations and related experiments. A point load at the free-end of a cantilever requires a triangular beam shape. Compared to a classical rectangular shape the electrical area energy density is three times larger. A maximum area energy density value of 35 nJ/mm2 is measured for the triangular beam shapes. A uniform load as occurring for fluid-actuated energy harvesting calls for a triangularcurved beam shape and is also superior to classical geometries. Keywords: MEMS generator, piezoelectric, energy harvesting, conversion, fluid-actuated INTRODUCTION CONCEPT State of the art piezoelectric MEMS generators typically harvest mechanical energy that is based on environmental vibrations [1, 2, 3 and 4]. These generators are based on spring-mass configurations that show the best efficiency when the resonant frequency of the harvester and the dominant frequency of the vibration match. Consequently, each generator design has to be specific and typically requires a vibration source with dominant spectral acceleration peaks that are time-invariant regarding amplitude and frequency. So, drift phenomena of vibrational frequency spectra caused by environmental variations (e.g. temperature, humidity) dramatically reduce the efficiency of such generators. Moreover, vibrations that are interfered by high static accelerating forces (e.g. centrifugal forces) are not efficiently suited for energy harvesting by springmass based generators. Vibration-based energy harvesters that operate in a non-resonant mode are able to overcome these drawbacks. [5] presents a miniaturized non-resonant inductive generator. Comparable MEMS-based generators are still be missing. Piezoelectric MEMS generators introduced in this work are designed for alternative excitation scenarios. The primary energy source is not based on an accelerating force field that is indirectly coupled into the generator via an inertial mass. Here, the primary energy is directly coupled into the piezoelectric structure of the generator. The primary energy can either be a fluid-based energy (e.g. fluidic pressure impulse) or a mechanical force that directly deforms the piezoelectric structure. In the following, piezoelectric MEMS generator geometries are presented that are optimized for these alternative excitation scenarios. The generation of adequate fluidic respectively mechanical forces and a reasonable coupling into the energy harvester is not discussed in this work. In general, the considered MEMS generators consist of piezoelectric cantilevers. The excitation scenarios make an additional inertial mass redundant. The mass of the cantilever is in the 10-6 gram range what makes the structure quite insensitive towards high static accelerating forces. The mode of coupling the primary energy into the piezoelectric cantilever has a large impact on an optimum beam shape. Figure 1 shows two typical loading conditions for a constant force F. Figure 1: Typical loading conditions for cantilevers: a) point load at free-end of the beam, and b) uniform load over the whole length of the beam. The bending moment Mp(x) for a point load at the free-end of the cantilever at x=L is expressed to: x⎞ ⎛ M p ( x ) = F ⋅ L ⋅ ⎜1 − ⎟ L ⎝ ⎠ (1) and the bending moment Mu(x) for a uniform load results in: M u (x ) = 1 x⎞ ⎛ ⋅ F ⋅ L ⋅ ⎜1 − ⎟ 2 ⎝ L⎠ 2 (2) A classical rectangular beam shape with length L, width 2⋅w0, and thickness t is presented in Figure 2. Figure 2: Classical rectangular beam shape. Here, the curve shape w(x) is constant over the beam length and can be expressed as: w(x ) = w0 (3) The area moment of inertia I(x) results in: 2 ⋅ w(x ) ⋅ t 3 12 ⋅ L I (x ) = (4) The mechanical stress σ(x) can be calculated based on the equations (1) respectively (2) and (4): σ (x ) = M p / u (x ) I (x ) ⋅t (5) The transversal piezoelectric effect results in the electrical voltage V(x): V (x ) = − d ε ⋅ t ⋅ σ (x ) On the one hand the clamped region of the cantilever shows the maximum mechanical stress and contributes the most to the electrical energy. The predominant rest of the volume is quite ineffective regarding the energy harvesting. On the other hand this effect results in an electrical voltage distribution. But a real implementation requires planar electrodes which forces equipotential surfaces respectively a constant voltage. This can lead to an unwanted back coupling from the electrical to the mechanical domain especially for piezoelectric materials with strong electromechanical coupling. Here, the deformation of the cantilever is retarted resulting in a decreased efficiency. However, the discussed negative effects can be overcome by a suitable geometry. An optimum design enables a homogeneous mechanical stress distribution within the lateral beam direction. This directly results in a fixed electrical voltage distribution – equipotential surface – so that the entire piezoelectric volume evenly contributes to the energy transduction. Equation (5) shows such a solution. Bending moment and area moment of inertia must follow an identical dependency in x so that the mechanical stress distribution becomes a constant value. This can easily be accomplished by choosing the right curve shape w(x) because it is directly proportional to the area moment of inertia (see Eq. (4)). Figure 3 presents the optimum beam shapes for both point and uniform load. (6) with the piezoelectric constant d and the permittivity ε. The electrical area energy density wpiezo can be expressed as: x= L w piezo = 1 d2 t⋅L ⋅ ⋅ ⋅ w(x ) ⋅ σ 2 (x ) dx (7) A x =0 2 ε ∫ with the cantilever area A. The mechanical stress, the electrical voltage and the electrical area energy density of the rectangular beam shape for both point load and uniform load are summarized in Table 1. The equations for the mechanical stress show a spatial dependence. This results in two drawbacks. Table 1: Physical quantities for rectangular beam shape for point load and uniform load. Point Load σ (x ) cσ ⋅ (L − x ) V (x ) cV ⋅ (L − x ) w piezo wp Uniform Load cσ 2 ⋅ (L − x ) 2⋅L cV 2 ⋅ (L − x ) 2⋅L wu Figure 3: Optimum beam shapes: a) point load at free-end of the beam, and b) uniform load over the whole length of the beam. The curve shape, the mechanical stress, the electrical voltage and the electrical area energy density of the optimized cantilevers for both point load and uniform load are composed in Table 2. Table 2: Physical quantities for optimum beam shapes for point load and uniform load. w(x ) Point Load x⎞ ⎛ w0 ⋅ ⎜1 − ⎟ ⎝ L⎠ σ (x ) cσ ⋅ L V (x ) cV ⋅ L w piezo 3⋅ wp 2 with cσ=6·F/(w0·t ), cV=-6·d·F/(w0·t), wp=3·d2·F2·L3/(ε·w02·t3), wu=0.45·d2·F2·L3/(ε·w02·t3) Uniform Load x⎞ ⎛ w0 ⋅ ⎜1 − ⎟ ⎝ L⎠ cσ ⋅L 2 cV ⋅L 2 5 ⋅ wu 2 The optimized triangular beam shape in case of a point load shows a constant mechanical stress respectively electrical voltage. Moreover, the area energy density is three times larger compared to a rectangular beam shape. In the event of a uniform load the optimized triangular-curved beam shape also presents a constant characteristic regarding mechanical stress and electrical voltage. The optimized beam shape provides an area energy density value that is five times larger in comparison to the rectangular beam shape. Even assuming that the rectangular beam shape utilizes the whole device area best the triangular beam shape with half the area reaches 150% of electrical energy and the triangular-curved beam shape with a third of the area achieves 167% of electrical energy compared to the classical rectangular beam shape. DESIGN Figure 4 presents a fully processed 6” SOI-wafer containing various piezoelectric cantilever structures for different load scenarios. A single device that is optimized for a uniform load can be seen in Figure 5. piezoelectric layer is made of a self-polarized PZT thin film with a thickness of 1.4 µm that is processed via sputtering technology [6]. The bimorphic stack can cope without a carrier layer. Figure 6 presents the layer compostion of a bimorphic stack. Figure 6: Detailed SEM picture of a piezoelectric bimorphic stack (optional Si-based carrier layer is not shown). In contrast to Figure 5 where the cantilever is spacious released the cantilever can also be released in a way that the structure is inherently enclosed within a proper fluidic channel. Figure 7 presents a corresponding detail of a bimorphic cantilever with a narrow fluidic channel. Figure 4: Fully processed 6” SOI-wafer containing piezoelectric cantilever structures of various shapes. Figure 7: Detailed SEM picture of a piezoelectric bimorphic beam tip enclosed within a narrow (50µm) fluidic channel. EXPERIMENTS Figure 5: SEM picture of a single triangular-curved piezoelectric cantilever which is an optimum for a uniform load. There are two species of piezoelectric beam stacks – monomorphic and bimorphic. This refers to the number of piezoelectric layers. The monomorphic stack has a single piezoelectric layer and requires an additional carrier layer (e.g. 5 µm Si) in order to fix the neutral fiber outside the piezoelectric material. The First measurements of monomorphic rectangular and triangular beam shapes have been done. The piezoelectric cantilevers were excited by a mechanical deflection at the free-end and then abruptly released in order to see the decay of the natural oscillations. Based on these measurements the optimum external resistive load was determined. Figure 8 shows an optimum impedance matching between the piezoelectric impedance and an external resistance of 6.67 kΩ. Furthermore, the dependency of the electrical quality factor regarding the ambient pressure is characterized and displayed in Figure 9. For this particular cantilever structure quality factors of more than 100 were found in case of atmospheric pressure. Triangular Beam Shape Theory 35.0 80 60 40 20 (w0 = 1.5 mm / L = 3.0 mm) Rectangular Beam Shape (w0 = 1.5 mm / L = 3.0 mm) P l 30.0 i h (T i l Mechanical Destruction Electrical Energy Density [nJ/mm2] Normalized Electrical Energy [%] 40.0 Measurement 100 25.0 20.0 15.0 10.0 5.0 0 100 1000 Resistive Load [Ω] 10000 Mechanical Destruction 0.0 100000 0.0 0.2 0.4 0.6 0.8 1.0 1.2 1.4 1.6 1.8 2.0 Free-End Deflection [mm] Figure 8: Normalized electrical energy depending on an external resistive load (impedance matching). Figure 11: Electrical energy density depending on beam deflection of the free-end. 600 CONCLUSION Electrical Quality Factor 500 400 300 200 100 0 0.01 0.1 1 10 100 1000 Ambient Pressure [mbar] Figure 9: Electrical quality factor of a piezoelectric cantilever depending on ambient pressure. Figure 10 shows the maximum electrical voltage for both triangular and rectangular beam shapes depending on the initial beam deflection of the freeend of the cantilever. It can be clearly seen that the triangular beam shape tolerates a considerably larger deflection. Furthermore, at a comparable deflection level the achieved electrical voltage is larger in the case of the triangular beam shape. Li (T i l This work is supported by the “Bundesministerium für Bildung und Forschung”, Germany, (reference 16SV3336) and contributes to the project „ASYMOF Autarke Mikrosysteme mit mechanischen Energiewandlern für mobile Sicherheitsfunktionen“. [1] B Mechanical Destruction Maximum Electrical Voltage [V] (w0 = 1.5 mm / L = 3.0 mm) Rectangular Beam Shape (w0 = 1.5 mm / L = 3.0 mm) 0.5 ACKNOWLEDGEMENT REFERENCES 0.6 Triangular Beam Shape Depending on the load scenario there is an optimum beam shape where the resulting mechanical stress respectively the generated electrical voltage is constant over the whole lateral beam area. A point load at the free-end of a cantilever requires a triangular beam shape. Compared to a classical rectangular shape the electrical area energy density value is three times larger. This was successfully proven by suitable experiments on piezoelectric cantilever test structures. The maximum area energy density value for triangular beam shapes was measured to 35 nJ/mm2. A uniform load calls for a triangular-curved beam shape and is also better performing than rectangular beam shapes. 0.4 0.3 [2] 0.2 0.1 [3] Mechanical Destruction 0.0 0.0 0.2 0.4 0.6 0.8 1.0 1.2 1.4 1.6 1.8 2.0 Free-End Deflection [mm] Figure 10: Maximum electrical voltage depending on beam deflection of the free-end. The corresponding electrical area energy density values are presented in Figure 11. The area energy density values of the triangular beams are between two and three times larger compared to the rectangular beam. This is in accord with the theoretical estimations. The maximum area energy density for triangular beam shapes was measured to 35 nJ/mm2. [4] [5] [6] I. Kuehne, et al: A New Approach for MEMS Power Generation Based On A Piezoelectric Diaphragm, Sensors and Actuators A: Physical, 142(1) (2008), pp. 292-297. F. Lu, et al: Modeling and Analysis of Micro Piezoelectric Power Generators for Micro-Electromechanical-Systems Applications, Smart Materials and Structures, 13(1) (2004), pp. 57-63. Y. Ammar, et al: Wireless sensor network node with asynchronous architecture and vibration harvesting micro power generator, Proceedings of sOc-EuSAI Conference 2005, pp. 287-292. Y. B. Jeon, et al: MEMS Power Generator with Transverse Mode Thin Film PZT, Sensors and Actuators A: Physical, 122(1) (2005), pp. 16-22. B. J. Bowers, et al: Spherical Magnetic Generators for Bio-Motional Energy Harvesting, Proceedings of PowerMEMS 2008, pp. 281-284. M. Schreiter, et al: Sputtering of Self-Polarized PZT Films for IR-Detector Arrays, Proceedings of ISAF 1998, pp. 181-185.