Document 14385346

advertisement

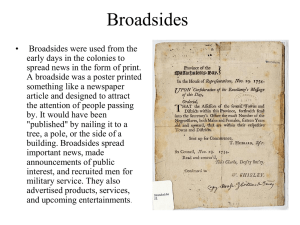

Sarah F. Williams School of Music swilliams@mozart.sc.edu 803-­‐777-­‐1759 Final Report USC Office of the Provost Humanities Grant Project Title: “Semester Leave to complete the manuscript for Damnable Practises: Representations of Early Modern English Witchcraft in Broadside Balladry and Popular Song” Grant Amount: $10,000 (Semester course buy out) Project Summary: I received a Humanities Grant in 2011 that was originally intended for a Spring 2012 course buy out in order to complete my book manuscript Damnable Practises: Performing Witches and Dangerous Women through Seventeenth-­‐Century English Broadside Ballads and their Music. For personal and departmental scheduling reasons, I negotiated leave for the Fall semester of 2011 instead. As a result, my goals and outcomes shifted slightly and are outlined below. My book, described by one reviewer at Ashgate Press as a “groundbreaking” study, fills a gap in current humanities scholarship by examining literary ephemera like the broadside ballad through the lens of musicological, gender, and performance studies. Historians have, for decades, scrutinized broadside ballads as tabloid evidence of everyday life in early modern England. Likewise, musicologists have catalogued their tunes and literary scholars have traced the thematic elements in their verses. These studies have, however, categorized the broadside as a fixed historical object, a print artifact examined in isolation, or a tune divorced from its text. I seek, rather, to examine the broadside through a multi-­‐ disciplinary methodology, taking into consideration its original function as a dynamic performative work situated in a unique cultural context. I aim to reconstruct how seventeenth-­‐century listeners heard witchcraft and disorder, and how the broadside ballad and its associated corpus of tunes was capable of both reflecting and shaping contemporaneous attitudes toward various forms of female transgression and their acoustic qualities. This multi-­‐faceted methodology has allowed my work to ultimately become trans-­‐disciplinary, moving beyond categorization as singularly musicological, literary, historical, or performative. Activities: My grant period was very productive. Since my leave was originally intended for Spring 2012, I pushed my research timetable back one semester. Therefore, my time during Fall 2011 was first spent completing revisions on a peer-­‐reviewed journal article for the Journal of Seventeenth-­‐Century Music, a version of which serves as Chapters 2 of my book. The reader reviews from this article greatly improved my book chapter. Williams, S.F. / 2 Chapter 2 offers the heretofore unexplored musical, theatrical, literary histories of the small set of popular tunes that accompany broadsides depicting witchcraft and female domestic crimes. The complicated and interrelated histories of tunes accompanying witchcraft and domestic crime ballads were dependent upon the communal experience of ballad sales, performance, and consumption for transmission. The first portion of this chapter elucidates the communal and didactic nature of broadside balladry and how popular songs were transmitted through the public performance, visual display, and sale of ballads. Turning to the tunes themselves, this chapter parses out the tangled histories of the three most common tunes used to accompany witchcraft, female violent crime, and cautionary broadsides. I cross-­‐reference tunes from the ballad trade with theatrical works, popular literature, and the histories of their associated genres. Based on feedback from colleagues, I also decided to expand the scope of Chapter 3. Through an examination of early modern theories excess, female physiology, and the efficacy of music, Chapter 3 posits that early modern English witches and dangerous women were categorized and represented not only by their social status or gender, but also by their musical and acoustic habits as described in broadside texts. Unruly women were often the focus of witchcraft accusations in early modern England due to their excessive natures—from their very biological make up to their unrestrained tongues. There were, however, gradations of offense—that is, a domestic scold was committing social hierarchy crimes as opposed to a murderess or a woman in league with the devil. Broadsides, however, used remarkably similar language to describe the excessive aural properties of each of these related character types. This chapter first outlines those agreements by examining the perceived power of wicked words and voices according to early modern occult philosophers and the dangers of excess outlined by sixteenth and seventeenth century medical treatises, marriage handbooks, and vernacular health guides. This chapter focuses particularly on the textual descriptions in broadsides of domestic scolds, murderesses, and witches, providing case studies for each category. After I finished revisions on Chapters 2 and 3, I also completed Chapter 1 and drafted Chapter 4. Chapter 1 provides definitions and context crucial to the understanding of how popular song, culture, print, and religion worked in concert and often conflict to communicate the acoustic properties of female malfeasance to seventeenth-­‐century English audiences. This portion of my book contextualizes witchcraft and female malfeasance through the lens of the English controversy over women, folkloric beliefs, anti-­‐Catholic sentiment, and the cheap print trade. English society was politically and culturally charged over religious issues at the turn of the seventeenth century including debates over Catholicism, Puritanism, and mainstream Protestantism to the marginalization of rural people and foreign immigrants. The language used to describe Catholics was similar to the depictions of witches—that is, bestial and grotesque. Grotesque imagery and language in the early modern era used to describe animals, Catholics, and the elderly were endowed these groups with bestial qualities of hybridity—located somewhere between human, beast, and the demonic. This seemingly “elite” controversy found its way into broadside ballad texts during the seventeenth century. Williams, S.F. / 3 Finally, Chapter 4 examines the performative and visual aspects of the broadside ballad, and how they could support, or subvert, the representation of female crime and acoustic excess as communicated by the ballad and its popular song. As outlined in Chapter Two, the visual display of broadside ballads was common practice in the early modern era. The woodcut images on broadsides, frequently reused because of their expense, were also capable of communicating extra-­‐musical ideas to the consumer. Beyond the immediacy of woodcut imagery on broadsides, the reception of different texts paired with ballad tunes could also be informed by the singing body of the performer, rendering the melody an even more powerful communicative tool. Needing to attract customers amidst the noisy din of London’s marketplaces and fairs, the skills of the balladmonger, however rudimentary, could encourage communal singing, the successful sale of broadsides, and the memorability and popularity of a tune. Understanding the immediacy and social power of broadside ballads through the lens performance and as a visual image informs how these multimedia cultural artifacts could support, or subvert, the representation of female crime and the supernatural as communicated by the ballad text and its accompanying song. I submitted sample chapters to Ashgate Press in early 2012. Reader reports from Ashgate suggested some revisions in scope and organization that required additional work on the manuscript during 2012. After the contract was granted, I negotiated a final manuscript submission date of 31 December 2013. Outcomes: In addition to producing another peer-­‐reviewed journal article for the Journal of Seventeenth-­‐Century Music during the grant period, I also made significant headway on my book manuscript. My book is under contract with the Music Studies division of Ashgate Press. Ashgate’s reputation for interdisciplinary publications, particularly popular music, women and gender, and early modern studies, is unparalleled. For example, their notable series “Women and Gender in the Early Modern World” is in its fourteenth year; an essay collection titled Ballads and Broadsides in Britain, 1500-­‐1800, which I had the opportunity to review, appeared in 2010; and a collection of which I am a part, Gender and Song in Early Modern England, is forthcoming. Since my scholarship is informed by and appeals to Shakespearean scholars, literary historians, scholars of performance studies, and musicologists alike, Ashgate is the ideal press for this book. The Humanities Grant provided the crucial time and momentum to complete the sample chapters that eventually helped me secure a publishing contract for this project. Without teaching release during the Fall semester—an opportunity not afforded to junior faculty in the School of Music—the publication contract and timeline for this book would not be a reality.