Four Monologues: Book Arts Project Report

advertisement

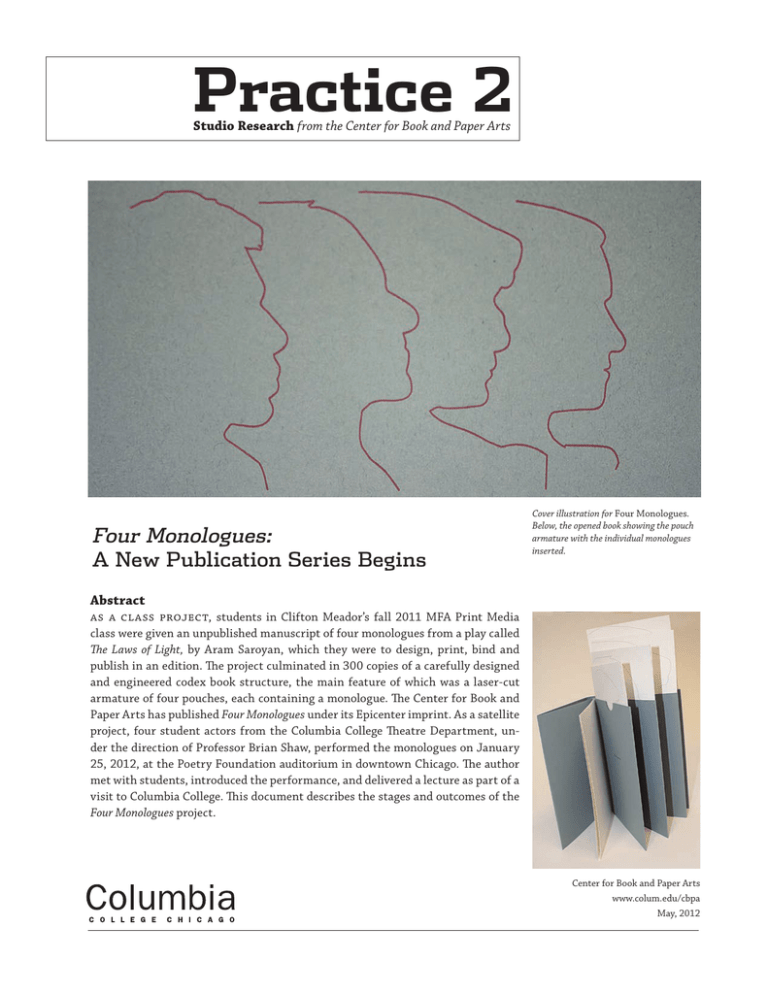

Practice 2 Studio Research from the Center for Book and Paper Arts Four Monologues: A New Publication Series Begins Cover illustration for Four Monologues. Below, the opened book showing the pouch armature with the individual monologues inserted. Abstract As a class project, students in Clifton Meador’s fall 2011 MFA Print Media class were given an unpublished manuscript of four monologues from a play called The Laws of Light, by Aram Saroyan, which they were to design, print, bind and publish in an edition. The project culminated in 300 copies of a carefully designed and engineered codex book structure, the main feature of which was a laser-cut armature of four pouches, each containing a monologue. The Center for Book and Paper Arts has published Four Monologues under its Epicenter imprint. As a satellite project, four student actors from the Columbia College Theatre Department, under the direction of Professor Brian Shaw, performed the monologues on January 25, 2012, at the Poetry Foundation auditorium in downtown Chicago. The author met with students, introduced the performance, and delivered a lecture as part of a visit to Columbia College. This document describes the stages and outcomes of the Four Monologues project. Center for Book and Paper Arts www.colum.edu/cbpa May, 2012 From the Series Editor I’ve always believed that an essential part of a poet’s education is to become a publisher. My own first work was published in two chapbooks that I designed and printed many years ago, assisted by a very bemused print shop employee in Providence, Rhode Island, who taught me about paper size, binding, typesetting, and much else. When every syllable of a poem — and each extravagance of the imagination — costs you money, and you don’t have a lot of money, you learn something tactile and real about Pound’s slogan, “dichten = condensare”—”to compose poetry is to condense.” I got an ISBN number, called myself The Smoke Shop Press (because I lived then above a smoke shop), and the rest was not history. But I learned a lot. And when I cut my editorial teeth later on at such places as Partisan Review, Salamander, and Harvard Review, what I knew about layout and printing gave embodiment to such fantasies I had about being an editor, let alone being a writer. Then, too, that phrase about how New Directions books were “published for James Laughlin” lingered deliciously. Poetry has a staff of five people to put out a monthly literary magazine, and we still design, copyedit, proofread, and typeset the thing by ourselves. But obviously the mechanics of literary publishing have come a long Jenny Garnett proudly shows off a completed cover enclosure, accompanied by fellow MFA candidates Elizabeth Gilder, Chris Saclolo, and Michelle Graves during the hand-binding process. way since I spent those many hours in the back room of a small shop with a printing press in front of me and ink all over my hands and clothes: we have all kinds of online systems to take us far away from ink, Xacto blades, paste, and dangerous machinery. Yet paper and ink, at present, is still with us, and the romance lingers. And it’s not enough to live your life behind a computer screen and think of poems as consisting of printed out sheets of word-processed documents. Not long ago, through poetry, a shared love of Artie Shaw, and having a publisher in common, Aram Saroyan — one of my heroes! — and I became friends. He let me see a work entitled Four Monologues, which he called exfoliations on the relationships among Boris Pasternak, Osip Mandelstam, Anna Akhmatova, and Nahdezda Mandelstam. The monologues, along with a translation of Mandelstam’s poem on Stalin, are from a play called The Laws of Light. It kindled something in me, and I don’t mean Kindle — I instantly knew I wanted to see this work into the world. I talked to my ingenious colleague Fred Sasaki, who connected me with our Printers’ Ball collaborators at the Columbia College Chicago Center for Book & Paper Arts. When I brought the monologues to the legendary Steve Woodall and Clifton Meador, it was just a great notion. But the next thing I knew we had a project to involve their talents and those of their brilliant students to design and produce a book. Everybody went away to think for a while. And with Aram’s extremely generous blessing, the students came up with something unaccountably apt and beautiful: a hand-printed, hand-sewn book consisting of four pockets, bound together, holding each piece of the work. The book makes tangible, as does Aram’s piece, the poignant fact that these four writers were both brought together by writing and the printed page and separated tragically by the events of history. We decided to use the imprint at the Center that also publishes such notable things as the Journal of Artists’ Books: Epicenter. And now the first copies in an edition of 300 have been assembled and are selling all over the country. Photos alone, as they say, cannot do the book, or Aram’s writing, justice. I hope anybody reading this will locate a copy of the book, in which so many dreams have been fulfilled. I want to thank Fred, Steve, Clifton, and the gifted, dedicated crew who put their skills to work on the project: Jenny Garnett, Boo Gilder, Michelle Graves, Hannah King, Jackie McGill, Jenna Rodriguez, Christopher Saclolo, and Claire Sammons. I’m grateful to all of them for letting me be their catalyst in bringing poetry, printing, theater, and history together. Above all, of course, it’s history that counts. As explained in the introduction to the book, Mandelstam was arrested in Moscow in 1934 for writing that poem denouncing Stalin. “Barely avoiding execution — thanks in large part to the efforts on his behalf of Boris Pasternak and a number of others — he was exiled to Voronezh. In 1937, he was allowed to return to Moscow; then in 1938 he was rearrested and was last seen in December of that year, feeding off the garbage heap of a transit camp near Vladivostok at the far eastern end of Russia.” We live, deaf to the land beneath us, Ten steps away no one hears our speeches… But in books, we remember. —Don Share, Senior Editor, Poetry magazine Monologue folios: Boris Pasternak, Osip Mandelstam, Anna Akhmatova, and Nadezhda Mandelstam. Assembled pieces slowly come together to create the complete work. The group of artists, CCC students, faculty, curator, and organizers in Caracas. Introduction to Four Monologues During the years when Joseph Stalin ruled the Soviet Union, Boris Pasternak, the poet and author of the epic novel Doctor Zhivago, lived a hard life, though not as hard as the lives of the three comparable poets of his day— Osip Mandelstam, who died during the purge year of 1937 while still in his forties; Anna Akhmatova, who survived the murder of her husband and the imprisonment of her son to live to the relatively old age of 76; and Marina Tsvetaeva, who went into exile and then returned on the eve of the Second World War, only to hang herself a few months after her repatriation. Pasternak was a man who seemed touched by a benign destiny that eludOsip Mandelstam, circa 1934 ed the other three. “Leave that cloud dweller alone,” Stalin is supposed to have decreed vis à vis Pasternak to his underlings, who went about making hell and havoc for anyone else who dared to keep the artist’s penchant for equivocation, ambiguity, irresolution, and in essence the delicacy of a pre-revolutionary self alive. Socialist realism, the art that would implant the proper ideals and ambitions in the Russian people en masse, was the usual travesty that ensues when government decides to dictate consciousness. Imagine if Jesse Helms had instructed Bernard Malamud or John Updike on how to write. Unfortunately, the scene seems less remote than one might hope. But in Russia it happened programatically and with lethal repercussions for disobeying orders or, perhaps more accurately, for not falling into proper psychological alignment. In the year 1926, before Stalin had both hands on the wheel of state, Tsvetaeva and Pasternak and Rainer Maria Rilke were in ecstatic three-way correspondence. As a young woman Akhmatova had lived in Paris where she sat for a Modigliani drawing. Later she allied herself with Mandelstam and the poetic school of acmeism, an antidote to symbolism not unlike the imagism Pound found in the work of his former University of Pennsylvania classmate, H.D. [Hilda Doolittle]. Here were the true Russian modernists of their generation—but the curve of history lay directly in their paths, and how they dealt with it is one of the central dramas of the age. One aspect of the story is how these poets, all with Jewish origins, variously embraced Christianity. Fated to walk through the valley of the shadow of death, they seemed to find as much or more in the religion banished by the Communist state than in their own, which had never been welcomed in their country. Here is a striking passage of dialogue from an early page of Doctor Zhivago: …Now what is history? It is the centuries of systematic explorations of the riddle of death, with a view to overcoming death. That’s why people discover mathematical infinity and electromagnetic waves, that’s why they write symphonies. Now, you can’t advance in this direction without a certain faith. You can’t make such discoveries without spiritual equipment. And the basic elements of this equipment are in the Gospels. What are they? To begin with, love of one’s neighbor, which is the supreme form of vital energy. Once it fills the heart of man it has to overflow and spend itself. And then the two basic ideals of modern man—without them he is unthinkable—the idea of free personality and the idea of life as sacrifice. Mind you, all this is still extraordinarily new. There was no history in this sense among the ancients. They had blood and beastliness and cruelty and pockmarked Caligulas who had no idea of how inferior the system of slavery is. They had the boastful dead eternity of bronze monuments and marble columns. It was not until after the coming of Christ that time and man could breathe freely. It was not until after Him that men began to live toward the future. Man does not die in a ditch like a dog—but at home in history, while the work toward the conquest of death is in full swing; he dies sharing in this work. Ouf! I got quite worked up, didn’t I? But I might as well be talking to a blank wall. So the character, a minor one in the narrative, pulls himself up short, but in the meantime one can’t help harboring the suspicion that one has been eavesdropping on the poet Pasternak in a striking ventriloquil episode. Zhivago wasn’t a character to everyone’s liking—by some he was considered a bit passive—but the book as a whole effectively broke the cold war’s Iron Curtain. People all over the world fell in love with the massive ensemble of players with their myriad intertwined destinies, and perhaps even more with the Russian landscape, evoked even in translation with touches of unmistakable genius. Here was a great modernist writer who effectively abandoned modernism to write a huge nineteenth century-style novel and simultaneously poems which put aside a natural gift for the striking image for an even more satisfying accuracy. The natural object itself is always the adequate symbol, so Ezra Pound and William Carlos Williams had instructed. And Pasternak in remote Russia seemed to hear them more clearly than anyone else. When the Weather Clears, Pasternak’s last poems, was about exactly that, a clearing after a storm—and also about the thaw that occurred when Khrushchev replaced Stalin and, in the final years of his life, Pasternak was awarded the Nobel prize for literature. During the same period I read Doctor Zhivago I came across Amanda Haight’s groundbreaking and, in its own terms, unsurpassable literary biography, Anna Akhmatova. I was never engaged by Akhmatova’s writing to the same degree as I was by Pasternak’s, but she has emerged through memoirs as the most lovable of the quartet, and lines she has uttered in conversation, recalled by memoirists, have the indelible ring of psychological and historical benchmarks. “How Mandelstam’s poem on Stalin. Saroyan at the Columbia College Chicago Theatre Department’s open rehearsal for Four Monologues. can you argue with your own biography?” she said. And: “Only someone who has listened to the radio in Russia for the last 25 years really understands Communism.” Both Pasternak and Ahkmatova, it should be said, along with Mandelstam and Tsvetaeva, had been in their pre-revolutionary youth the equivalent of rock stars. Their readings took place in huge venues and were sold out. Akhamatova had been a slender aristocratic beauty who wrote clipped, cryptic love lyrics that have a parallel of sorts in H.D.’s early work. She cut a figure, both physically and poetically. Two decades later, standing in the freezing cold in a long line of people at the gates of Lubianka prison waiting to get packages to their imprisoned loved ones, Akhmatova, who was waiting to get a package to her imprisoned son, was recognized by a woman ahead of her in the line who turned around to face her. “Can you write this?” the woman asked. “I can,” Akhmatova said. Probably we can date her transformation to that direct commission from an anonymous Russian woman on behalf of all the people suffering through wave after wave of Stalinist terror, which would result in her epic “Requiem.” By the time her young protégé Joseph Brodsky knew her, Akhmatova retained only her aristocratic nose. The rest of her had turned into a rotund peasant woman, albeit with a face full of the candor and light of one who knew the worst and still delighted in people. At one point Brodsky, this outspoken poet who professed himself a non-believer, refers to Akhmatova as an exemplary Christian. Indeed, it’s as if these poets under siege by Stalin found in their own self-styled Christianity a kind of physics of emotional and psychological survival. Or so we might say, anyway, of the two survivors, Pasternak and Akhmatova. Terrorism of this vintage seemed to work in a relatively simple and recognizable way. The mise en scene usually requires a tipping over of standard practices in the matter of human dignity—murder on the one hand, severe cruelty and humiliation on the other—to serve as a reminder to everyone in the drill that the terrorist is not to be defied. A refinement is that the terrorist could be quirky and irrational. We see this in Stalin’s case in the instance of Pasternak, who practiced his own quirky defiance of the dictator’s inhuman posture. When Stalin’s wife died, there were rumors that he had murdered her, and Pasternak, eschewing the public statement of sympathy issued by the Writers Union, sent Stalin a personal message in which he made ominous mention of having somehow witnessed the scene. What one catches a glimpse of here seems less an act of irrational bravery on Pasternak’s part than a delicate issuance of empathy for the gruesome contorted figure of Russia’s long nightmare. In the face of the Stalinist terror, Pasternak simply refused to stop being himself, which is the terrorist’s first requirement. If Stalin was a paranoid psychotic who wouldn’t hesitate to murder when he sniffed out even a whiff of defiance, that inclination to murder gave him the power to duplicate his own unbalanced state of mind in the rank and file of the Soviet Union at large, writers and artists included. You’re a family man, with a wife you love and children you love, and you witness an act of defiance that would be anathema to the great leader. Or perhaps you’re not positive whether it was or wasn’t an act of defiance. Still, if it was, and you don’t report it, you and your family could suffer severe consequences, perhaps even be executed. What do you do? The greatest power of the terrorist, in the end, may be the ease by which he is able to clone himself in his subjects, his paranoia on the one hand and his cruelty on the other. What one sees in these four poets is an inability to rally to the cause and be cloned. More or less in spite of themselves, there was something almost sleepily autonomous about their nervous systems and the way they went on being interested in the usual things: the trees in spring, a beautiful melody, falling in love. It was literally death defying, their continuing to be human in the Stalinist state. And for two of the four, the consequences were in fact lethal. —Aram Saroyan Open rehearsal with (left to right) Ben Peterson, Robert Francis Curtis, Kathryn Acosta, and Professor Brian Shaw. The Chicago Performance of Four Monologues The strangeness of objects, I’d suggest, rises from the jarring sense that they are inert matter that seems to serve as individual witness of distant places, far gone events. They are there, present, but they are also holding, in some sense, the absent sites they come from. ­—Alice Rayner, Ghosts: Death’s Double and the Phenomena of Theatre the first time I laid eyes on, and felt the physical structure of this book, I knew the pockets into which each piece of text were inserted would find resonance in the actions of the performers. The structure of the book itself was evocative of the relationship one often feels with text: a private relationship with words on paper. Words to be carried on the body. Words to be pulled out and savored through a physical embrace of hand, arm, eye, mind, and memory. My first experience with the text therefore was visual and tactile. Reading the text reinforced these visual and tactile impressions. Each character in Four Monologues is a well-known Russian writer. Within the monologues, they speak directly about seeking expression through language. Anna Ahkmatova claims, “If you find a form, the subject reveals itself.” As I read through the text, it struck me that some of the language felt too crafted to be delivered as if it was being said for the first time. There was language in each monologue that had clearly seen a strong editorial hand; the language had been shaped by powerful literary minds seeking a precise linguistic expression of thought, feeling, and experience. And so I went through the text with each actor to identify where language may be emerging in the moment, and where language had been previously crafted and was being delivered by a strong literary voice. We then cut the monologues into sections. The actors memorized certain portions of the text and delivered them as if they were speaking in the present moment. And they carried certain portions of the text on their bodies, pulling Above: Alyssa Thordarson as Anna Akhmatova. Below: Robert Francis Curtis as Boris Pasternak. through each other’s memories. The period of time they lived and worked through was infused with death. Stalin’s purges of the late 1930’s killed millions (including Osip Mandelstam), and was followed by the carnage of WWII. It was an era in which the individual—and especially the Russian individual—could be quickly and completely erased. But within the enormity of this historical period, each of these characters navigated an intense personal and creative life. Essentially, each character seems to be asking the following in relation to the era they lived in: Did I show courage? Did I act honorably? Could I have done otherwise? Will my work survive? each segment out and reading it as a considered expression of thought. Each actor was tasked with the choice of where these segments would lie on their body, and how they would pull them from those locations: front pocket, breast pocket, back pocket, etc. The monologues were performed as a combination of the written word and the remembered word. In this way, the physical structure of the book was given representation in performance. The slips of paper the actors read from held the “absent site” of the book that had been created. Just as the physicality of the book provided inspiration for the gesture of the performance, the performance space at the Poetry Foundation provided inspiration for the shape of the performance. A simple walkway behind the glass walls of the theater created a space in which characters could be seen at a remove from the presence of audience and performer inside the theater itself. (We called this insulating walkway “the thermos”.) This offered the opportunity to stage the monologues as a simple ghost story. And these characters haunt each other. They orbit And they look to each other as they ponder the answers to these questions. For Boris Pasternak, Osip Mandelstam becomes in the years after his death, a “bold spur to thought, a vivid interlocutor…” For Nadezhda Mandelstam, she “hung on in memory and dreams to Osip’s voice, his curious look, his power to seize upon something with the fervor of his whole soul…” For Anna Ahkmatova, she acknowledged that Pasternak “fell in love under Stalin”, and in doing so, “he defeated the terror with that simple act, and then transposed the emotion into a great story…” For Osip Mandelstam, he discovered that “only in loss do we men finally seem to fathom the simple joy of knowing this creature we married whose pilgrimage was tenderness.” Mandelstam leaves us with a final ghostly image of his wife and Anna Ahkmatova sitting together in a tiny room in a boarding house in the middle of the madness of World War II: Stalin stopping Hitler. What do you make of two great souls sitting quietly together in a room, in a maelstrom? As Pasternak says, “Nobody dies. Nobody who was alive to you for a moment in your life.” I would like to thank Kathryn Acosta, Robert Curtis, Ben Peterson, and Alyssa Thordarson for their hard work and excellent performances. —Brian Shaw, Professor Columbia College Chicago Department of Theatre The cast, from left to right: Ben Peterson as Osip Mandelstam; Kathryn Acosta as Nadezhda Mandelstam; Alyssa Thordarson as Anna Akhmatova; Robert Francis Curtis as Boris Pasternak. The Joy of Community: The Four Monologues Project Last spring, as part of Clifton Meador’s Print Media class, my classmates and I began a collaborative project working with Don Share, Senior Editor of Poetry magazine. The text was Four Monologues by poet Aram Saroyan. In the piece, Saroyan writes from the perspective of four different Russian writers/poets: Boris Pasternak, Osip Mandelstam, Anna Akhmatova, and Nahdezda Mandelstam. Our task was to take the text and create a physical receptacle for it. These four writers lived during the Russian Revolution, some witnessing the rise of the Soviet Union. Their work was often done in secret, transferred and transmitted orally as much as on the page. The realities of the historical context in which these writers lived became very important to us as we began to design the book. That the content of the writing and the history of the speakers be reflected in the creative structure of the book was crucial. So, we spent months making mock-ups, through the spring semester and into the summer. We discussed many options and finally, out of a lot different ideas, the design was born. It would have four pockets, one for each writer. The reader would have to extract the monologues from the pockets to read the text. We made a mock-up and waited expectantly for the approval of both the writer and Don Share. When it was approved, we began production on an edition of 300 books. The structure was not simple. Four pockets would make up the interior of the book, and an additional folio would wrap around them displaying the introduction to the monologues as well as our colophon. Our book required offset and letterpress printing, the use of a laser cutter, and hours upon hours of binding—folding and hand sewing each book. It took us almost an entire year to finish the edition. The assembly in process. The laser cutter in action on a different project, cutting out script lettering. Having the project completed was a wonderful feeling. But it was the events that surrounded the release of the book that truly brought both the writing and the process of constructing the book to life. These events involved not only the Center for Book and Paper Arts, but also the Poetry Foundation and the Theater Department at Columbia College Chicago, not to mention Aram Saroyan himself. On the night the book debuted at the Poetry Foundation, Aram Saroyan gave a fascinating talk about the origins of his idea and what led him to write Four Monologues, and four actors from the Columbia College Theater Department performed. As they began their recitations, I watched as they pulled pieces of paper from the pockets of their clothes, reading from these small slivers and returning them to the pockets and pulling out more. It was an incredible experience to see the bodily, performative manifestation of our book. The best part about this project was the collaboration and community involvement—not just the collaboration of students but of the Chicago community and our Columbia College Chicago community at large. Each year this process will be repeated with a new text for a new group of Interdisciplinary Book and Paper Arts and Arts and Media students. And each year there will be a new collaboration with the Poetry Foundation and the potential for further engagement across disciplines, multiple processes informing and building upon each other in an extraordinary way. —Hannah E. King MFA candidate Maria Virginia Rodriguez Four Monologues— Digital Edition The Center for Book and Paper Arts has received an Arts in Media grant from the National Endowment for the Arts (NEA) to produce mobile tablet apps representing existing artists’ books, and to commission new works in digital media with material counterparts. For this project, Expanded Artists’ Books: Envisioning the Future of the Book, the Center has designated Four Monologues as the project’s first book to extend into the digital realm. With a focus on transferring the book’s dynamic physical structure onto a tablet platform, the digital version will feature media and interactive touch features. Launching summer of 2012, Expanded Artists’ Books aims to widen the audience for the artist’s book, while encouraging new forms of the genre in electronic media. For more information, please go to: CBPA-Applications@colum.edu. Next in the Publication Series The second book in this series will be The Dark Threw Patches Down Upon Me Also, by Ben Lerner. Lerner’s recent novel Leaving the Atocha Station has garnered enthusiastic reviews from The New Yorker, Bookforum, and many other publications. Produced by Book and Paper Print Media students under the direction of Inge Bruggeman, the book will appear later this year. Participants Epicenter Literary Series Editor Don Share Senior Editor, Poetry magazine Four Monologues Design + Production Clifton Meador Professor Interdisciplinary MFA in Book and Paper Columbia College Chicago MFA Book and Paper Candidates: Jenny Garnett Elizabeth Gilder Michelle Graves Hannah King Jackie McGill Jenna Rodriguez Christopher Saclolo Claire Sammons Four Monologues Staged Reading Brian Shaw Professor, Department of Theatre Columbia College Chicago Kathryn Acosta as Nadezhda Mandelstam Robert Francis Curtis as Boris Pasternak Ben Peterson as Osip Mandelstam Alyssa Thordarson as Anna Akhmatova Additional Four Monologues production and distribution support from Gina Ordaz and Tracey Drobot. Practice 2 was edited by Jessica Cochran and Steve Woodall; template design by Clifton Meador; production design by Kathi Beste. Photography by Kathi Beste, Inge Bruggeman, and Jackie McGill. Practice is available for download at www. colum.edu/bookandpaper founded in 191 2 Gallery of photographs from the open rehearsal of Four Monologues: Above, left to right: Ben Peterson, with Robert Francis Curtis in the background; Kathryn Acosta. Below, left to right: Christina Colosimo and Nina Liewehr in discussion with author and poet Aram Saroyan. For more images, please visit www.colum.edu/bookandpaper