Family Functioning, Marital Satisfaction and Social

advertisement

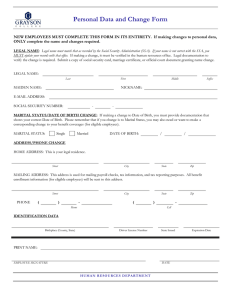

RESEARCH ARTICLE Family Functioning, Marital Satisfaction and Social Support in Hemodialysis Patients and their Spouses Hong Jiang1, Li Wang2, Qian Zhang1, De-xiang Liu1, Juan Ding1, Zhen Lei1, Qian Lu3 & Fang Pan1*† 1 Department of Medical Psychology, Shandong University School of Medicine, Jinan, Shandong, China Kidney Disease Centre, Jinan Central Hospital Affiliated to Shandong University, Jinan, Shandong, China 3 Department of Psychology, University of Houston, Houston, Texas, USA 2 ABSTRACT A growing number of studies have demonstrated the importance of marital quality among patients undergoing medical procedures. The aim of the study was to expand the literature by examining the relationships between stress, social support and family and marriage life among hemodialysis patients. A total of 114 participants, including 38 patients and their spouses and 38 healthy controls, completed a survey package assessing social support, stress, family functioning and marital satisfaction and quality. We found that hemodialysis patients and spouses were less flexible in family adaptability compared with the healthy controls. Patients and spouses had more stress and instrumental social support compared with healthy people. Stress was negatively associated with marital satisfaction. Instrumental support was not associated with family or marital outcomes. The association between marital quality and support outside of family was positive in healthy individuals but was negative in patients and their spouses. Family adaptability was positively associated with support within family as perceived by patients and positively associated with emotional support as perceived by spouses. In conclusion, findings suggest that social support may promote adjustment depending on the source and type. Future research should pay more attention to the types and sources of social support in studying married couples. Copyright © 2014 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. Received 31 October 2012; Revised 12 August 2013; Accepted 12 September 2013 Keywords family functioning; marital quality; hemodialysis; stress; social support *Correspondence: # Professor Fang Pan, Department of Medical Psychology, Shandong University School of Medicine, 44 , Wenhua Xi Road, Jinan, Shandong, 250012, China. † Email: panfang@sdu.edu.cn Published online 28 January 2014 in Wiley Online Library (wileyonlinelibrary.com) DOI: 10.1002/smi.2541 Introduction A growing number of studies suggest the importance of family function and marital adjustment among patients with chronic diseases (Clare et al., 2012; Pereira, Daibs, Tobias-Machado, & Pompeo, 2011; Tadros et al., 2011). End-stage renal disease (ESRD) is one of the chronic diseases causing a high level of disability in different domains of the patients’ lives, leading to stress reactions (Abraham, Venu, Ramachandran, Chandran, & Raman, 2012; Edgell et al., 1996). Several studies showed that ESRD had a negative impact on family functioning (Anthony et al., 2010; Park et al., 2012), but few link the stress reaction, social support and patients’ family function and marital state (de Paula, Nascimento, & Rocha, 2008; Watson, 1997). The goal of this study was to investigate the family and marital 166 life of hemodialysis patients with ESRD using a stress and social support framework. The theoretical framework of stress and coping proposes that stress is a two-way process; the environment produces stressors and the individual finds ways to deal with them (Folkman, 1984; Folkman & Lazarus, 1983). Stress occurs when environmental demands exceed personal resources for coping with the demand (Manne & Sandler, 1984; Coyne & Downey, 1991; Ahlert & Greeff, 2012). Cognitive appraisal is central to the stress and coping processes as it determines how an event is perceived and, therefore, operates as an essential mediator between the event and the outcome. It should be noted that chronic disease and treatment can cause stress, which will have a negative impact on family function and marital satisfaction (Myaskovsky et al., 2005). Stress Health 31: 166–174 (2015) © 2014 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. H. Jiang et al. Studies have shown that patients with ESRD undergo serious stress experiences (Cukor et al., 2007; Finkelstein & Finkelstein, 2000). Patients with ESRD often go through hemodialysis therapy, an expensive and time-intensive treatment requiring fluid and dietary restrictions. Long-term dialysis therapy could result in dependence on caregivers, a loss of freedom, and family members and partners of patients having to adjust the schedule of treatment and also experiencing stress symptoms (Lin, Lee, & Hicks, 2005). Hemodialysis impacts every life aspect of patients and their spouses. Studies suggested that family members of hemodialysis patients are faced with lower quality of life, more mental health problems and potential complications and disruption of family life (AL-Jumaih, Al-Onazi, Binsalih, Hejaili, & Al-Sayyari, 2011; Al Eissa et al., 2010; Reynolds, Garralda, Jameson, & Postlethwaite, 1988; Sathvik, Parthasarathi, Narahari, & Gurudev, 2008). Patients with ESRD and their spouses often have stress reactions and complex adaptation in couple relationships (Khaira et al., 2012). But, there are few studies focused on the relationship between stress and family and marital adjustment of patients on dialysis and their spouses. Increasing evidence addresses the role of social support in the course of chronic disease as a protective factor. Social support could reduce the level of negative emotion and physiological response, improving the health state of the body (Tavallaii et al., 2009). Social support is defined as the perception that an individual is a member of a network in which one can give and receive affection, help and obligation (Untas et al., 2011). It can be received from family members, friends, colleagues and medical personnel. Greater social support has been linked to better health outcomes in community and clinical samples (Cohen et al., 2007). Most of studies have examined the relationship between social support and patient adherence to medical care as well as quality of life (Christensen et al., 1992; Kara, Caglar, & Kilic, 2007; Thong, Kaptein, Krediet, Boeschoten, & Dekker, 2007; Kutner, Zhang, McClellan, & Cole, 2002; Helgeson, 2003; Tell et al., 1995). Those studies showed a strong correlation between perceived social support and several measures of health-related quality of life in dialysis patients. However, there is less information about the association between social support and family and marital adjustment in dialysis patients. Therefore, it is important to examine the functioning of social support on family and marital life among ESRD patients. Previous studies indicated that individuals with ESRD perceiving more social and family support have been associated with lower mortality risks (Christensen, Wiebe, Smith, & Turner, 1994; Kimmel et al., 1998). Seeking social support during stressful times could expand the family bond and enhance the relationship between family members and their relatives (McLean & Hales, 2010; Tezel, Karabulutlu, & Sahin, 2011). For Stress Health 31: 166–174 (2015) © 2014 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. Family and Marital Life in Hemodialysis Patients example, parents in one study reported increased closeness with family and greater bonding between the child and his or her mother when social support was sought (de Paula et al., 2008). Therefore, it has possibility that patients on dialysis and spouses would receive increased social support; this social support in turn would be associated with better adjustment in family and marital life according to stress theory. Family function and marital satisfaction play an important role in quality of life amongst hemodialysis patients (Anthony et al., 2010; Park et al., 2012). Assessments of both family function and quality of marriage can yield basic information for psychological family intervention. The circumflex model of family functioning characterizes families on two orthogonal dimensions: cohesion and flexibility (adaptability) (Olson, 1986). Cohesion refers to the emotional bonds between family members; flexibility refers to the quality and expression of the family’s leadership, organization, roles and relationship rules. Well-functioning families are considered balanced and fall mid-range on each dimension. Poorly functioning families are considered unbalanced on these dimensions, falling either low (e.g. disengaged and rigid) or high (enmeshed and chaotic) on these characteristics. Over the family life cycle and in response to stress, families are expected to shift along these dimensions in predictable ways (Cervera, 1994; García-Huidobro, Puschel, & Soto, 2012). Therefore, in the current study, in addition to assessing marital satisfaction and quality, we assessed family functioning factors (i.e. family cohesion and adaptability) as indicators of adjustment. Furthermore, previous studies regarding social support and adjustment have revealed mixed findings. One study showed a strong correlation between perceived social support and several measures of health-related quality of life in dialysis patients (Helgeson, 2003), whereas a crosssectional study of black and white women and men did not find such results (Tell et al., 1995). These findings suggest the importance of conducting additional studies among non-white samples. In this study, we planned to investigate the relationships between stress, social support, family functioning and marital quality among Chinese dialysis patients. We also investigated whether the level of stress, perceived social support, family functioning and marital quality among patients and their spouses differ compared with healthy individuals. Because long-term dialysis is a stressful event, we hypothesized that hemodialysis patients would experience higher levels of stress than their spouses, who would experience higher levels of stress than healthy controls (hypothesis 1). Because stress may elicit social support and extended family members were more likely to provide social support to patients, we also hypothesized that patients and their spouses would receive more social support than healthy controls (hypothesis 2). Because families under stress may have limited resources for maintaining family and marital 167 H. Jiang et al. Family and Marital Life in Hemodialysis Patients life, patients and spouses would have lower family life and marriage quality compared with healthy controls (hypothesis 3). We also hypothesized that lower levels of stress and higher levels of social support would be associated with higher family and marital quality (hypothesis 4). Furthermore, because social support could be given financially, emotionally, by spending time with the patient and so on, and social support could be from family and outside of the family, we would also explore whether the type and sources of social support mattered. Method Participants Patients were recruited from dialysis centre of Medical College Hospital in Jinan, China from May, 2010 to July, 2011. The criteria for inclusion were: ESRD patients over 22 years of age and of either sex; regular hemodialysis twice a week for at least 6 months; able to speak or read the local language and able to consent to participate in the study. In addition, their spouses agreed to participate in the same study. Patients were excluded if they had malignant tumours or multiple organ system failure, major hearing impairment (inability to hear loud speech even with a hearing aid), rejection episodes or underwent any major surgical interventions in the previous 3 months. Healthy individuals in the control group were matched based on major demographic factors and were recruited from the general population by conducting a survey in health centre of the same hospital and on a voluntary basis, excluding those with major diseases such as hypertension, coronary heart disease and diabetes. The control group served as a control for both the patients group and spouses group. The residing area of all subjects was in Jinan City (urban population). Approval for the study was obtained from the Institutional Ethics Committee of Medical College of Shandong University. Written consent was obtained from each subject. The purpose of the study, voluntary participation, confidentiality and freedom to discontinue at any time without being left untreated, were understood by patients prior to their participation. Standardized questionnaires were used to obtain data. Figure 1 showed the sampling and flow of the study. Measurements Family functioning: family cohesion and flexibility The Chinese version of the family adaptability and cohesion evaluation scales (FACES II-CV) was used to rate actual experience of family function (Phillips, Zheng, & Zhou, 1993). There are two subscales of FACES II-CV in evaluating family cohesion and flexibility, respectively. Test-retest reliability ranged from 0.84 to 0.91 and Cronbach’s alpha coefficients are 0.85 and 0.73, respectively. Family cohesion is the emotional bonding that family members have with each other; the dimension includes items such as ‘family members try to support each other when the family faces difficulty’ and ‘family members enjoy free time Figure 1. Sampling and flow of study 168 Stress Health 31: 166–174 (2015) © 2014 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. H. Jiang et al. together’. Family flexibility is the ability of the family system to adjust its rules, provide structure and adjust relationship patterns in response to changes; the subscale included such items as: ‘Each family member is involved in making major family decisions’ and ‘we like to use a new method to solve the problem’. The items were rated on a five point scale. Moderate scores in cohesion and flexibility sub-dimensions indicate a balanced family. Extreme lower or higher scores indicate an imbalanced family. Family cohesion is divided into four types, including loose, free, intimate and entangled, and family flexibility is divided into four types as well: irregular, flexible, regular and inflexible, according to the determination point of the mean and one standard deviation score. Martial satisfaction and quality The Chinese version of the marital inventory ENRICH (Evaluating & Nurturing Relationship. Issues, Communication & Happiness) was used to judge the degree of satisfaction in marriage (Cao, Jiang, Li, Hui Lo, & Li, 2013). ENRICH included 12 factors: marital satisfaction, personality compatibility, the couple exchange, conflict resolution, economic arrangements, leisure activities, sexual life, children and marriage, the relationship between friends and relatives and the role of equality and belief consistency. The validity and reliability of ENRICH shows internal consistency (alpha) ranges from 0.68 to 0.86 in every dimension and testretest correlation coefficients ranges from 0.77 to 0.96. The discrimination reliability is from 85%–90%. Global measurement of 12 factors and marital satisfaction is used in this study, with a higher score indicating better marital quality and marital satisfaction (Fowers & Olson, 1989). Stress reaction The Chinese version of the Stress Responses Questionnaire consisted of 28 items on a 1–5 rating scale, including psychological response, physical response and behavioral response based on the stress response model. Total scores indicate intensive stress reaction. Cronbach’s alpha coefficient of Stress Responses Questionnaire is 0.902, correlation coefficient with Self-Rating Anxiety Scale (SAS) and Self-Rating Depression Scale (SDS) are 0.585 and 0.574, respectively (Zhong, Jiang, Wu, & Qian, 2004). Social support The Chinese versions of the Social Support Rating Scale and Perceived social support scale (PSSS) were used in the study. Social Support Rating Scale has three dimensions, including instrumental support, emotional support and utilization of social support. Instrumental support comes from objective and visible help, including material assistance, financial support and social networks. Such support is independent of individual feelings. Emotional support is the social state of the Stress Health 31: 166–174 (2015) © 2014 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. Family and Marital Life in Hemodialysis Patients individual’s emotional experiences and satisfaction, it is closely related to the individual’s subjective feelings (Xiao, 1999). PSSS emphasizes the individual’s perceived social support from various sources, such as family members and friends. There are two dimensions in PSSS: family support within family and support outside family (Jiang, 2001). Statistical analysis Statistical analyses were carried out using SPSS version 18.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, USA). Univariant relationships were determined between sociodemographics (gender, education, working status and family members); X2 test was used to analyze the degree of family flexibility, and mental scales scores were analyzed with one-way ANOVA and least significant difference test. Pearson’s correlation was used to determine the correlation between stress reaction, social support, family functioning and marital satisfaction. All statistical tests were two-tailed, and P < 0.05 was regarded as being statistically significant. Results Demographic characteristics of the subjects are documented in Table I. There were no significant differences in gender, education, working status or number of family members among the three groups. Family functioning and marital quality and satisfaction The comparison of the FACES II-CV and ENRICH scores of hemodialysis patients and spouses with the control group did not yield any significant differences in family cohesion, family flexibility and marital quality or marital satisfaction. Types of family flexibility analyses showed that 13.15% of non-patients thought their family was inflexible, whereas 36.8% of patients and 31.57% of spouse rated their family as inflexible. These results indicate that there were more inflexible family types in the patient group compared with families in the control group (Table II; X2 = 6.343, P < 0.05). Comparison of stress reaction and social support Stress reaction and social support differed significantly in three groups (Table III). Hemodialysis patients and their spouses had higher scores in stress reaction than the control group (P < 0.01, P < 0.05) and more instrumental social support than the control group (P < 0.01). Correlation analysis between stress reaction, social support, family functioning and marital satisfaction Stress was negatively associated with marital satisfaction across the three groups (P < 0.001). Subjective support was positively related with family cohesion in the control group (P < 0.005) and with family 169 H. Jiang et al. Family and Marital Life in Hemodialysis Patients Table I. Demographic characteristics of the subjects (n = 114) Items age (years) ± SD male/female education high school graduate college graduated post graduated employment employment retired family numbers control group (n = 38) % patient group (n = 38) % spouse group (n = 38) % F P 56.5 ± 12.1 19/19 55.9 ± 12.4 20/18 55.8 ± 12.9 18/20 1.781 0.442 1.661 0.173 0.657 0.195 14 (36.8%) 15 (39.5%) 9 (23.7%) 14 (36.8%) 16 (42.1%) 8 (21.0%) 14 (36.8%) 16 (42.1%) 8 (21.0%) 1.561 0.214 22 (57.9%) 16 (42.1%) 3.49 ± 1.14 22 (57.9%) 16 (42.1%) 3.51 ± 1.17 23 (60.5%) 15 (39.5%) 3.46 ± 1.14 0.020 0.980 No significant differences in demographic characteristics of the subjects (One-way ANOVA and LSD-test). Table II. Comparison of types of family flexibility Items un-regulation flexible regulation inflexible 2 control group (n = 38) % patients group (n = 38) % spouse group (n = 38) % X 10 (26.31) 13 (34.21) 10 (26.31) 5 (13.15) 6 (15.78) 8 (21.05) 10 (26.31) 14 (36.81) * 5 (13.16) 9 (23.68) 11 (28.94) 13 (34.21) * 2.428 1.877 0.330 6.343† *P < 0.05 difference compared with control group (chi-square test). † P < 0.05. Table III. Comparison of stress reaction and social support (Mean ± SD) Items Stress Reaction Instruments Support Emotional Support Support utilization Support within family Support outside family control group (n = 38) patients group (n = 38) spouse group (n = 38) F 47.79 ± 15.53 8.17 ± 2.97 16.00 ± 4.24 7.69 ± 2.04 16.00 ± 4.24 28.02 ± 7.57 63.97 ± 28.25* 10.13 ± 2.98* 16.75 ± 3.94 7.62 ± 2.16 16.57 ± 3.59 28.83 ± 8.22 59.02 ± 22.76† 10.20 ± 3.09* 16.75 ± 3.94 7.49 ± 2.07 16.75 ± 3.94 29.48 ± 8.46 5.111‡ 4.570‡ 0.385 0.089 0.385 0.312 *P < 0.01; †P < 0.05 difference compared with control group (one-way ANOVA and LSD-test); ‡P < 0.01. flexibility in the spouse group (P < 0.005). Instrumental support was not related with family functioning or martial quality in any of the groups. Support outside family was positively related to marital quality and satisfaction in healthy individuals (P < 0.001) and negatively related to marital quality in patients (P < 0.001) and their spouses (P < 0.001). Support within family was associated positively with family cohesion and adaptability among patients and healthy individuals (P < 0.001, respectively) but not among spouses (Table IV). Discussion Previous studies have demonstrated the role of stress and social support on quality of life among patients with chronic illnesses. However, few investigated the relationships between stress, social support and family 170 and marital life. This study used a case control method to test the differences in stress, social support, family and martial life, and their relationships among patients, spouses and healthy controls. We hypothesized that patients and spouses would have higher stress and social support and worse family and marital adjustment compared with healthy people; and family and marital adjustment would be negatively associated with stress and positively associated with social support. Our hypotheses were only partially supported. Unexpected findings about martial quality and stress reaction of patients and spouses also appeared and revealed a complex picture of the adaptation and relevant risk and protective factors among patients and spouses. Consistent with our hypotheses, we found that hemodialysis patients and spouses were less flexible in Stress Health 31: 166–174 (2015) © 2014 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. H. Jiang et al. 0.330* 0.164 0.048 0.032 0.092 0.343* 0.100 0.177 0.069 0.383* 0.469* 0.210 0.079 0.301 0.261 0.471* 0.071 0.080 0.191 0.512* 0.307 0.057 0.171 0.001 0.336* 0.604* 0.225 0.045 0.466* 0.392* 0.317 0.334** 0.159 0.016 0.003 0.099 0.099 0.251 0.386* 0.001 0.280 0.226 0.054 0.490* 0.290 *P < 0.001; **P < 0.005 (Pearson’s correlation test). 0.303 0.201 0.140 0.199 0.111 0.017 0.037 0.151 0.443* 0.053 0.373** 0.384** 0.189 0.597* 0.224 Stress reaction Emotional support Instrument support Support within family Support outside family patient patient patient Items control patient spouse control family flexibility family cohesion Table IV. Correlation between family functioning, martial quality, stress reaction and social support spouse control marital quality spouse control marital satisfaction spouse Family and Marital Life in Hemodialysis Patients Stress Health 31: 166–174 (2015) © 2014 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. family adaptability. However, they did not differ in marital quality and satisfaction compared with the healthy controls. Consistent with our hypothesis, patients and their spouses exhibited higher levels of stress reactions than healthy people. However, patients and spouses did not differ in stress levels. Consistent with our hypothesis, stress was negatively associated with marital satisfaction across the three groups. Our results supported the argument that dialysis and stress reaction both decreased the family functioning. Furthermore, we found that patients and spouses received more instrumental social support compared with healthy people; however, instrumental support was not associated with family or marital outcomes. Emotional support was positively related with family flexibility in spouses and in family cohesion in healthy people, but patients, spouses and healthy people did not differ on perceived emotional support. Although support outside family was positively related to marital quality and satisfaction in healthy individuals, it was negatively related to marital quality in patients and their spouses. Support within family was associated with family cohesion and adaptability among patients and healthy individuals but not among spouses. These findings revealed a complex picture of the health implications of social support among patients. We discuss the findings and their implications in more detail in the succeeding text. The present study showed that patients in dialysis and their spouses had more serious stress reactions than non-patients, suggesting that the diagnosis of ESRD and treatment with hemodialysis might destroy the balance of mental and physical states in both patients and their spouses. Previous studies have shown that patients with ESRD encountered serious stress experiences and negative emotion, and depression was the main factor influencing quality of life (Cukor et al., 2007; Finkelstein & Finkelstein, 2000). One study reported that ESRD could affect the well-being of spouses as well as the patients (Davila, Bradbury, Cohan, & Tochluk, 1997). Couples in which one partner has ESRD and is on hemodialysis must adjust to an illness that requires patients to adhere to a strict treatment schedule (Devins, Hunsley, Mandin, Taub, & Paul, 1997). Our results support the conclusion that both patients in dialysis and their spouses have serious stress reactions. A previous study suggested that patients in dialysis had to face unpredictable health crises, which would impact their marital satisfaction (Daneker, Kimmel, Ranich, & Peterson, 2001). In this study, no differences in the levels of family functioning and martial quality were found among hemodialysis patients, their spouses or the control group. It seems that dialysis and stress reactions induced by disease and diagnosis did not impact the family functioning and marital quality at first glance, but we think that patients and their spouses had a complex adaptation to the period of disease. As 171 H. Jiang et al. Family and Marital Life in Hemodialysis Patients results further showed, there was a greater incidence of inflexible families in patients than non-patients, indicating that patients regarded their families as inflexible in adaptations to life changes. Dialysis is a time-intensive therapy (Al Eissa et al., 2010; Reynolds et al., 1988; Sathvik et al., 2008). One study showed that male patients reported more negative effects of dialysis on family life, social life, energy and appetite than female patients; longer dialysis duration was associated with adverse effects on finances, energy and living arrangements (Al Eissa et al., 2010). Our findings point out that although the family and marital functioning are good among patients and their family members, more attention should be paid to adaptation to change. Our findings also contributed to the vast literature on social support and suggest the importance of examining the types and sources of social support. In this study, instrumental support is the objective support, such as material and financial assistance. Emotional support is the individual’s emotional experiences and satisfaction related to the social state. It is common for Chinese people to receive instrumental support but not necessarily emotional support from relatives when they are sick. This may explain our results that patients and spouses receive more instrumental but not emotional support compared with healthy controls. However, despite the widespread belief in Chinese societies that instrumental support is helpful, we did not find that instrument social support was beneficial to family functioning and marital quality. Western scholars have argued that received support may not be beneficial because it is associated with a threat to self-esteem or one’s sense of independency, which in turn offset any benefits of received support (Bolger & Amarel, 2007; Uchino, 2009). This study also suggests that receiving instrumental support may offset benefits of received support in collective cultures. Furthermore, in Chinese cultures, receiving instrumental support often implies an obligation to reciprocate and thus may add a burden to those who feel that they could not return instrumental support. Future studies should further investigate the distinct mechanisms linking instrumental support to welling and linking emotional support to well-being. Our findings suggested that support within family was more important to patients’ family functioning and marital quality, whereas support outside of family was an interferential factor to marital satisfaction of patient and spouse. In other words, the function of social support also depends on the source of social support and who is receiving it. We found that support within family was associated with greater family cohesion and flexibility for both patients and healthy people. This is consistent with the idea that social support could decrease the stress reaction and improve well-being, including family functioning. In contrast, support outside family was associated with better marital quality among healthy people, but worse marital quality and satisfaction among patients and spouses. 172 There are two possible explanations. A previous study using a laboratory stress paradigm (Uno, Uchino, & Smith, 2002) showed that under stress situations women receiving support from supportive close friend had lower cardiovascular reactivity, but having support from ambivalent female friends resulted in higher cardiovascular reactivity. Perhaps, the support received from outside of family during non-stressful times may come from close friends with high quality relationship, whereas support received from outside of family during stressful times, such as acute or chronic illness, may come from those who feel obligated to help but may not really want to, thus resulting in ambivalence from the support provider. Our results support the idea that the quality of one’s relationship with the support provider is an important aspect when explaining the effect of social support on the physical health outcomes (Birmingham, Uchino, Smith, Light, & Sanbonmatsu, 2009). It is also possible that patients and their spouses may believe that support outside family would interfere with marriage and family life, or that obtaining support would lower their self-esteem, threat their sense of control or intensify their guilt of not being able to reciprocate. Our finding suggests that psychological interventions should focus on utilizing social support coming from family members, which could promote family quality in patients with chronic diseases. Future studies are needed to examine how and why the different sources of social support have opposite impacts on well-being. This study has several limitations, including selfreport and relatively small sample sizes. Future studies should test the conclusions in a larger sample size. Future research should also include family life as an additional domain for studying married couples and pay attention to more variables such as gender, age and dialysis duration and the ways in which these affected family and marital quality (Anthony et al., 2010; Eton, Lepore, & Helgeson, 2005). In conclusion, our findings suggest that stress poses challenges for family and marital life among patients and spouses. Despite the stress that patients and spouses experience, their family and marital lives appear to adapt well. Although social support coming from within the family may promote family quality among patients, social support outside of the family may interfere with marital life for both patients and spouses and emotional support is important for spouses to improve family life. Authors’ contributions Fang Pan devised the concept for the study, developed the study design, supervised data collection and analysis, drafted the manuscript, and was involved in study coordination and manuscript revision. Hong Jiang and Li Wang collected data. De-xiang Liu, Juan Ding and Zhen Lei performed the analyses. Qian Lu revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. Stress Health 31: 166–174 (2015) © 2014 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. H. Jiang et al. Family and Marital Life in Hemodialysis Patients Conflict of interest The authors have declared that no conflict of interests exists. REFERENCES Abraham, S., Venu, A., Ramachandran, A., Chandran, P. M., & Raman, S. (2012). Assessment of quality of life in patients on hemodialysis and the impact of counseling. Saudi Journal of Kidney Diseases and Transplantation, 23, 953–957. Ahlert, I. A., Greeff, A. P. (2012). Resilience factors associated with adaptation in families with deaf and hard of hearing children. American Annals of the Deaf, 157, 391–404. Al Eissa, M., Al Sulaiman, M., Jondeby, M., Karkar, A., Barahmein, M., Shaheen, F. A.,…Al Sayyari, A. (2010). Factors affecting hemodialysis patients’ satisfaction with their dialysis therapy. International Journal Nephrology, 2010, 342–346. AL-Jumaih A., Al-Onazi, K., Binsalih, S., Hejaili, F., & Al-Sayyari, A. (2011). A study of quality of life and its determinants among hemodialysis patients using the KDQOL-SF instrument in one center in Saudi Arabia. Arab Journal Nephrology Transplant, 4, 125–130. Anthony, S. J., Hebert, D., Todd, L., Korus, M., Langlois, V., Pool, R.,…Robinson, L. A. (2010). Child and parental perspectives of multidimensional quality of life outcomes after kidney transplantation. Pediatric Transplantation, 14, 249–256. Birmingham, W., Uchino, B. N., Smith, T. W., Light K. C., & Sanbonmatsu, D. M. (2009). Social ties and cardiovascular function: An examination of relationship positivity and negativity during stress. International Journal of Psychophysiology 74, 114-119. Bolger, N., & Amarel, D. (2007). Effects of social support visibility on adjustment to stress: experimental evidence. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 92, 458–475. Cao, X., Jiang, X., Li, X., Hui Lo, M. C., & Li, R. (2013). Family functioning and its predictors Acknowledgment National Key Technologies R & D Program (2009BA177B05). spouses. Alzheimer Disease and Associated Disorders, 26, 148–158. Cohen, S. D., Sharma, T., Acquaviva, K., Peterson, R. A., Jiang, Q. J. (2001). Perceived social support scale. Chinese Journal Behavioral Medical Science, (S), 41–42. Patel, S. S., & Kimmel, P. L. (2007). Social support Kara, B., Caglar, K., & Kilic, S. (2007). Nonadherence and chronic kidney disease: An update. Advances in with diet and fluid restrictions and perceived social Chronic Kidney Disease, 14, 335–344. support in patients receiving hemodialysis. Journal Coyne, J. C., & Downey, G. (1991). Social factors and of Nursing Scholarship, 39, 243–248. psychopathology: Stress, social support, and coping Khaira, A., Mahajan, S., Khatri, P., Bhowmik, D., processes. Annual Review of Psychology, 42, 401–425. Gupta, S., & Agarwal, S. K. (2012). Depression and Cukor, D., Coplan, J., Brown, C., Friedman, S., Crom- marital dissatisfaction among Indian hemodialysis well-Smith, A., Peterson, R. A.,…Kimmel, P. L. patients and their spouses a cross-sectional Study. (2007). Depression and anxiety in urban hemodialysis patients. Clinical Journal of the American Society of Nephrology, 2, 484–490. Renal Failure, 34, 316–322. Kimmel, P. L., Peterson, R. A., Weihs, K. L., Simmens, S. J., Alleyne, S., Cruz, I.,…Veis, J. H. (1998). Psycho- Daneker, B., Kimmel, P. L., Ranich, T., & Peterson, R. A. social factors, behavioral compliance and survival in (2001). Depression and marital dissatisfaction in urban hemodialysis patients. Kidney International, patients with end-stage renal disease and in their spouses. American Journal of Kidney Diseases, 38, 839–846. Davila, J., Bradbury, T. N., Cohan, C. L., & Tochluk, S. (1997). Marital functioning and depressive symptoms: evidence for a stress generation model. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 73, 849–861. Devins, G. M., Hunsley, J., Mandin, H., Taub, K. J., & Paul, L. C. (1997). The marital context of end-stage 54, 245–254. Kutner, N. G., Zhang, R., McClellan, W. M., & Cole, S. A. (2002). Psychosocial predictors of non-compliance in haemodialysis and peritoneal dialysis patients. Nephrology, Dialysis, Transplantation, 17, 93–99. Lin, C. C., Lee, B. O., & Hicks, F. D. (2005). The phenomenology of deciding about hemodialysis among Taiwanese. Western Journal of Nursing Research, 27, 915–929. renal disease: Illness intrusiveness and perceived Manne, S., & Sandler, I. (1984). Coping and adjustment changes in family environment. Annals of Behavioral to genital herpes. Journal of Behavioral Medicine, Medicine, 19, 325–332. 7, 391–410. Edgell, E. T., Coons, S. J., Carter, W. B., Kallich, J. D., McLean, L. M., & Hales, S. (2010). Childhood trauma, Mapes, D., Damush, T. M.,…Hays, R. D. (1996). A attachment style, and a couple’s experience of termi- review of health-related quality-of-life measures used nal cancer: Case study. Palliative & Supportive Care, 8, in end-stage renal disease. Clinical Therapeutics, 18, 887–938. 227–233. Myaskovsky, L., Dew, M. A., Switzer, G. E., McNulty, Eton, D. T., Lepore, S. J., & Helgeson, V. S. (2005). M. L., DiMartini, A. F., & McCurry, K. R. (2005). Psychological distress in spouses of men treated Quality of life and coping strategies among lung for early-stage prostate carcinoma. Cancer, 103, transplant candidates and their family caregivers. 2412–2418. Finkelstein, F. O., & Finkelstein, S. H. (2000). Depres- Social Science and Medicine, 60, 2321–2332. Olson, D. H. (1986). Circumplex Model VII: Validation among disaster bereaved individuals in china: sion in chronic dialysis patients: Assessment and studies and FACES III. Family Process, 25, 337–351. Eighteen months after the Wenchuan earthquake. treatment. Nephrology, Dialysis, Transplantation, 15, Park, K. S., Hwang, Y. J., Cho, M. H., Ko, C. W., Ha, I. S., PLoS One, 8, e60738. 1911–1913. Kang, H. G.,…Cheong, H. I. (2012). Quality of Cervera, N. (1994). Family change during an unwed Folkman, S. (1984). Personal control and stress and life in children with end-stage renal disease based teenage pregnancy. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, coping processes a theoretical analysis. Journal of on a PedsQL ESRD module. Pediatric Nephrology, 23, 119–140. Personality and Social Psychology, 46, 839–852. 27, 2293–2300. Christensen, A. J., Smith, T. W., Turner, C. W., Folkman, S., & Lazarus, R. S. (1983). If it changes it Holman, J. M., Jr., Gregory, M. C., & Rich, M. A. must be a process: Study of emotion and coping dur- (2008). (1992). Family support, physical impairment, and ad- ing three stages of a college examination. Journal of strengthening families of children with chronic renal Personality and Social Psychology, 48, 150–170. failure. Revista Latino-Americana de Enfermagem, herence in hemodialysis: An investigation of main and buffering effects. Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 15, 313–325. Christensen, A. J., Wiebe, J. S., Smith, T. W., & Turner, C. W. (1994). Predictors of survival among hemodialysis patients: Effect of perceived family support. Health Psychology, 13, 521–525. Clare, L., Nelis, S. M., Whitaker, C. J., Martyr, A., Markova, I. S., Roth, I.,…Woods, R. T. (2012). Marital relationship quality in early-stage dementia: Perspectives from people with dementia and their Fowers, B. J., & Olson, D. H. (1989). Enrich marital de Paula, E. S., Nascimento, L. C., & Rocha, S. M. The influence of social support on 16, 692–699. inventory a discriminant validity and cross-validation Pereira, R. F., Daibs, Y. S., Tobias-Machado, M., & assessment. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy, Pompeo, A. C. (2011). Quality of life, behavioral 15, 65–79. problems, and marital adjustment in the first year García-Huidobro, D., Puschel, K., & Soto, G.. (2012). Family functioning style and health: Opportunities for health prevention in primary care. British Journal of General Practice, 62,e198-203. Helgeson, V. S. (2003). Social support and quality of life. Quality Life Research, Supply 1, 25–31. Stress Health 31: 166–174 (2015) © 2014 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. after radical prostatectomy. Clinical Genitourinary Cancer, 9, 53–58. Phillips, M., Zheng, Y. P., & Zhou, D. H. (1993). Chinese version of family adaptability and cohesion evaluation scales. Chinese Mental Health Journal, (S), 101. 173 H. Jiang et al. Family and Marital Life in Hemodialysis Patients Reynolds, J. M., Garralda, M. E., Jameson, R. A., & Tell, G. S., Mittelmark, M. B., Hylander, B., Shumaker, S. A., Postlethwaite, R. J. (1988). How parents and families Russell, G.,…Burkart, J. M. (1995). Social support and cope with chronic renal failure. Archives of Disease in health-related quality of life in black and white dialysis Childhood, 63, 821–826. patients. Anna Journal, 22, 301–308. women. International Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 9, 243–262. Untas, A., Thumma, J., Rascle, N., Rayner, H., Mapes, D., Lopes, A. A.,…Fukuhara, S. (2011). The associ- Sathvik, B. S., Parthasarathi, G., Narahari, M. G., & Tezel, A., Karabulutlu, E., & Sahin, O. (2011). Depression ations of social support and other psychosocial Gurudev, K. C. (2008). An assessment of the quality of and perceived social support from family in Turkish factors with mortality and quality of life in the dial- life in hemodialysis patients using the WHOQOL- patients with chronic renal failure treated by hemodial- ysis outcomes and practice patterns study. Clinical BREF questionnaire. Indian Journal Nephrology, 18, ysis. Journal Research Medecine Science, 16, 666–673. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology, 6, 141–149. Thong, M. S., Kaptein, A. A., Krediet, R. T., 142–152. Tadros, A., Vergou, T., Stratigos, A. J., Tzavara, C., Hletsos, Boeschoten, E. W., & Dekker, F. W. (2007). Social Watson, A. R. (1997). Stress and burden of care in families with children commencing renal replacement M., Katsambas, A.,…Antoniou, C. (2011). Psoriasis: is it support predicts survival in dialysis patients. the tip of the iceberg for the quality of life of patients and Nephrology, Dialysis, Transplantation, 22, 845–850. therapy. Advances in Peritoneal Dialysis, 13, 300–304. their families? Journal of the European Academy of Uchino, B. N. (2009).What a lifespan approach might Xiao S. Y. (1999). Social support rating scale. Rating tell us about why distinct measures of social support scales for mental health. Chinese Mental Health Dermatology and Venereology, 25, 1282–1287. Tavallaii, S. A., Nemati, E., Khoddami Vishteh, H. R., Azizabadi Farahani, M., Moghani Lankarani, M., & have differential links to physical health. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships 26, 53–62. Journal, (S), 127–131. Zhong, X., Jiang, Q. J., Wu, Z. X., & Qian, L. J. (2004). Assari, S. (2009). Marital adjustment in patients on Uno, D., Uchino, B. N. & Smith, T. W. (2002). Rela- Effect of life event, social support, stress response on long-term hemodialysis a case–control study. Iranian tionship quality moderates the effect of social support coping styles in medical personnel. Chinese Journal Journal of Kidney Diseases, 3, 156–161. given by close friends on cardiovascular reactivity in Behavior Medecine Science, 13, 560–562. 174 Stress Health 31: 166–174 (2015) © 2014 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.