Affect as a mediator between self-efficacy and quality of

advertisement

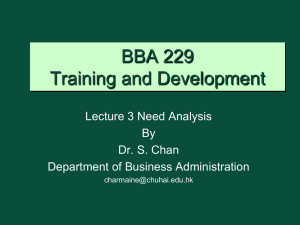

bs_bs_banner Original article Affect as a mediator between self-efficacy and quality of life among Chinese cancer survivors in China N.C.Y. YEUNG, MPHIL, Department of Psychology, University of Houston, Houston, TX, & Q. LU, MD, PHD, Department of Psychology, University of Houston, Houston, TX, USA YEUNG N.C.Y. & LU Q. (2014) European Journal of Cancer Care 23, 149–155 Affect as a mediator between self-efficacy and quality of life among Chinese cancer survivors in China Previous studies have shown that self-efficacy influences cancer survivors’ quality of life. As most of the relevant findings are based on Caucasian cancer survivors, whether the same relationship holds among Asian cancer patients and through what mechanism self-efficacy influences quality of life are unclear. This study examined the association between self-efficacy and quality of life among Chinese cancer survivors, and proposed affect (positive and negative) as a mediator between self-efficacy and quality of life. A sample of 238 Chinese cancer survivors (75% female, mean age = 55.7) were recruited from Beijing, China. Self-efficacy, affect (positive and negative) and quality of life were measured in a questionnaire package. Self-efficacy was positively associated with quality of life and positive affect, and negatively associated with negative affect. Path analyses revealed the direct effect from self-efficacy to quality of life and the indirect effects from self-efficacy to quality of life through positive affect and negative affect. The beneficial role of self-efficacy in Chinese cancer survivors’ quality of life and the mediating role of affect in explaining the relationship between self-efficacy and quality of life are supported. Future interventions should include self-care and affect regulation skills training to enhance cancer survivors’ self-efficacy and positive affect, as this could help to improve Chinese cancer survivors’ quality of life. Keywords: self-efficacy, affect, quality of life, Chinese, cancer survivors. INTRODUCTION Self-efficacy, the extent of a person’s confidence in his or her ability to execute a course of action, has been shown to be associated with people’s adaptation to cancer (Lev 1997). Previous studies have shown that self-efficacy is positively associated with physical and psychological quality of life and inversely associated with distress among different groups of cancer survivors (Hochhausen Correspondence address: Qian Lu, Department of Psychology, 126 Heyne Building, University of Houston, Houston, TX 77204-5022, USA (e-mail: qlu3@uh.edu). The authors declare no conflicts of interest with respect to authorship and/or publication of this article. The authors received no financial support for the research and/or authorship of this article. Accepted 14 August 2013 DOI: 10.1111/ecc.12123 European Journal of Cancer Care, 2014, 23, 149–155 © 2013 John Wiley & Sons Ltd et al. 2007; Howsepian & Merluzzi 2009; Mosher et al. 2010). Because studies examining the relationship between self-efficacy and quality of life were primarily conducted among Western populations, whether the same relationship holds among Asian cancer patients is unclear. In Chinese culture, coping with illness is largely a family affair (Liu et al. 2005). Emphasising filial piety, caring for the sick is also regarded as a duty and obligation to Chinese families. In the context of cancer adaptation, the immediate family is often the source of primary support. Chinese cancer survivors tend to rely on the interpersonal resources from family members to meet their practical and psychological needs. Qualitative studies have found that family members of Chinese cancer survivors actively participated in caregiving tasks, information seeking and treatment decision-making (Liu et al. 2005; Wong-Kim et al. 2005). Quantitative studies have found that family support was positively YEUNG & LU associated with Chinese cancer patient’s well-being (Sun & Stewart 2000; Chan et al. 2009). These suggest the critical role of family support in the well-being among Chinese cancer patients. Given that Chinese cancer patients are more likely to have readily available interpersonal resources from their family members, it is also important to examine if patients’ intrapersonal resources (e.g. perceived self-confidence in dealing with cancer-related stressors) influence their well-being. There is a paucity of studies examining the beneficial role of self-efficacy on well-being among Chinese cancer survivors. Findings could provide useful recommendations for planning the interventions for this population. In the literature, there is no conclusive evidence about the beneficial role of self-efficacy on well-being among Chinese cancer patients. One study in Hong Kong showed that self-care self-efficacy was positively associated with all subscales of the Short-Form Health Survey 36 among Chinese patients receiving intestinal stoma surgery (Wu et al. 2007). Similarly, a longitudinal study in Hong Kong showed that higher general self-efficacy at 1 week after breast cancer surgery was associated with lower psychological morbidity and higher social adjustment at 1-month follow-up (Lam & Fielding 2007). However, this study also showed that self-efficacy was positively associated with incongruence between patient’s expected outcome and actual outcome of the surgery, which in turn reduce psychological well-being and social adjustment. With these empirical inconsistencies, the first goal of this study was to clarify the associations of self-efficacy and quality of life among Chinese cancer survivors. The second goal of our study is to understand the pathways linking self-efficacy and well-being. Several potential mediators (e.g. optimism, benefit finding, positive social comparison) have been suggested to explain the relationship between self-efficacy and well-being in previous studies (Schulz & Mohamed 2004; Karademas 2006; Luszcynska et al. 2007). Johnston-Brooks et al. (2002) found that self-care self-efficacy mediated the association between self-efficacy and the physical outcome (HbA1c) among adults with Type I diabetes. Kershaw et al. (2008) found that hopelessness mediated the relationship between self-efficacy at baseline and mental quality of life at 8 months among 121 prostate cancer patients; while negative appraisal mediated the relationship between selfefficacy and physical quality of life. These studies show that self-efficacy may influence well-being through cognitive and behavioural mediators. However, remaining unknown is whether affect can be a potential mediator between self-efficacy and quality of life. 150 According to the Social Cognitive Theory, self-efficacy helps to attain a desired outcome, which in turn affects psychosocial functioning (Bandura 1977, 1997). It also suggests that self-efficacy creates positive affective states because it represents people’s confidence in using the skills necessary to cope with stress and mobilising resources to meet situational demands. People with higher self-efficacy may experience a lower level of negative emotions in a threatening situation because they recognise their ability to overcome obstacles and focus on opportunities (Bandura 1997). Empirical studies have also shown the beneficial effect of positive affect and the detrimental effect of negative affect on longevity and health outcomes among healthy and patient populations (Howell et al. 2007; Xu & Roberts 2010; Diener & Chan 2011). The Broaden-and-Build Theory (Fredrickson 2001) also proposes that positive affect and negative affect can function as determinants of well-being, not only as the indicators of well-being. It postulates that positive affect can broaden people’s scopes of cognition and build resources for future coping, which in turn can initiate upward spirals for better well-being. In contrast, negative affect can narrow people’s thought-action repertoires and thus reduces personal resources to cope with adversity, which in turn decreases well-being (Fredrickson & Joiner 2002). All these suggest that self-efficacy may influence well-being through affective pathways. Although affect has not been directly tested as a mediator between self-efficacy and quality of life in the literature, several studies have shown the association between affect and self-efficacy and the association between affect and cancer-related quality of life. Higher self-care selfefficacy has been found to be associated with higher positive affect, lower depression and emotional distress, and lower negative affect among cancer patients in Canada (Cunningham et al. 1991), Japan (Hirai et al. 2002; Kohno et al. 2010; Deno et al. 2012) and the USA (Campbell et al. 2004; Heitzmann et al. 2011). Quality of life has also been found to be positively associated with positive affect, and negatively associated with negative affect among different groups of cancer patients (Kessler 2002; Bower et al. 2005). One study in Israel also showed that self-efficacy influences quality of life by reducing perceived stress (Kreitler et al. 2007). All of these findings imply that a mediating relationship may exist between self-efficacy and quality of life through affect. This study thus aimed to address and clarify existing knowledge gaps by proposing affect as a mediator to explain the association between self-efficacy and quality of life. We hypothesised that self-efficacy would be positively associated with quality of life, and positive affect and negative affect would mediate the © 2013 John Wiley & Sons Ltd Quality of life among Chinese cancer survivors versions of the scales were compared and discussed. The translated scales were modified to reflect the intended meanings of the items in the original English version. Positive affect Quality of life Self-efficacy Affect Negative affect Figure 1. Hypothesised model. relationship between self-efficacy and quality of life (Fig. 1). METHOD Participants The sample consisted of Chinese cancer survivors (75% female) with a mean age of 55.7 (SD = 9.1, ranging from 33 to 75). Over 80% of participants were retired and 45% received an associate degree or a college education. A vast majority were married (90%). Over two-thirds (67%) of the participants were diagnosed with either Stage I or Stage II cancer. The most common types of cancer were breast (51.9%), uterine, cervical and ovarian (11.6%), and colorectal and intestinal (9.9%) with most of them (73.5%) having survived for at least 2 years after diagnosis. A majority of them had undergone surgery (95%), chemotherapy (81.1%) and Traditional Chinese Medicine treatment (82.4%). Recruitment Participants were recruited from cancer associations in Beijing, China. Chinese cancer patients who were able to read Chinese were eligible for this cross-sectional survey. Prospective participants were introduced to the study. Participants received an envelope with a questionnaire packet distributed by the staff at the cancer associations. Participants completed the questionnaires at home and then returned them in a sealed envelope. The questionnaires took approximately 40 min to complete. A total of 238 out of the 280 distributed questionnaires were returned, yielding a response rate of 85%. Relevant Institution Review Board approval was obtained. Measurements All scales were translated from English to Chinese and back-translated by two bilingual psychology graduate students. The forward-translated and back-translated © 2013 John Wiley & Sons Ltd Positive affect and negative affect were measured by the 16-item extended version of the Bradhurn Affect Balance Scale (Bradburn 1969). The scale consisted of nine items for positive affect and seven items for negative affect respectively. On a four-point scale (1 as never, 4 as always), participants were asked to indicate how frequently they experienced the given situations in the past week. Sample items were ‘things were going your way’ (positive affect) and ‘very lonely or remote from other people’ (negative affect). A higher mean score indicated a high level of the particular affect. The subscales were reliable and valid in previous studies (Folkman 1997; Billings et al. 2000). The Cronbach’s alphas for positive affect and negative affect in this sample were 0.85 and 0.82 respectively. Self-efficacy to cope with cancer The 33-item Cancer Behaviour Inventory (CBI) was used to measure participants’ level of self-efficacy towards coping with cancer (Merluzzi et al. 2001). On a sevenpoint scale (1 as not at all confident, 7 as totally confident), participants were asked to indicate their general level of self-confidence when coping with cancer. Sample items were ‘maintaining work activity’, ‘asking physician questions’ and ‘remaining relaxed throughout treatment’. A higher mean score indicated higher self-efficacy. The scale was reliable and valid in previous studies among cancer patients (Hochhausen et al. 2007; Mosher et al. 2010). The Cronbach’s alpha in this sample was 0.97. Quality of life Quality of life was measured by the Quality of Life – Cancer Survivors Instrument (QOL-CS) (Ferrell et al. 1995). On a six-point scale (0 as feeling very bad, 5 as feeling very good), participants were asked to report their current well-being in four dimensions (physical, psychological, social and spiritual well-being). Sum score of all items indicated their overall level of well-being, with a higher score representing better quality of life. The scale was reliable and highly correlated with the general version of Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy (FACT-G) (Ferrell et al. 1995). The Cronbach’s alpha in this sample was 0.93. 151 YEUNG & LU Table 1. Correlations among major variables (n = 238) (1) 1. Age 2. Gender 3. Education level 4. Marital status 5. Occupation status 6. Time since diagnosis 7. Stage of cancer 8. Self-efficacy 9. Positive affect 10. Negative affect 11. Quality of life Mean SD – −0.31** 0.13* −0.07 −0.32** 0.13* −0.08 0.14* 0.10 −0.25** 0.35** 55.7 9.1 (2) (3) (4) (5) (6) – −0.02 0.21** −0.07 −0.10 −0.01 −0.07 −0.10 0.10 – – – −0.13 −0.09 −0.14* 0.06 0.15* 0.04 0.07 – – – −0.11 0.01 0.07 −0.02 0.10 −0.02 – – (7) (8) (9) (10) (11) – −0.23** 0.45** 2.99 0.68 – −0.52** 1.73 0.65 – 124.53 24.73 – 0.04 −0.06 0.05 0.11 0.15* 0.02 0.11 0.02 −0.04 – – – 0.01 0.08 0.14* −0.26 0.15* – – – 0.13 −0.01 0.04 −0.19** – – – 0.45** −0.35** 0.53** 5.01 0.97 *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01. Coding for variables: Gender: male (1), female (2); Education level: middle school or below (1), high school (2), college or above (3); Marital status: not married (0), married (1); Occupation status: not full-time employed (0), full-time employed (1); Time since diagnosis: less than 1 year (1), 1–2 years (2), 2–5 years (3), more than 5 years (4). Demographic information (including gender, educational level, occupation), disease- and treatment-related variables (e.g. type of cancer, cancer stage, time since diagnosis, previous treatments) were also self-reported in the questionnaire. 0.44 0.30 Analytic plan RESULTS Descriptive statistics and correlations among major variables Descriptive statistics of major variables and Pearson correlation matrix among the major variables are presented in 152 0.23 Quality of life Self-efficacy –0.35 Descriptive statistics were computed for major variables. Pearson correlation analysis was conducted to examine the associations among variables. Missing data were less than 2% in the major psychological variables and were imputed by expectation-maximisation algorithm (Dempster et al. 1977). These analyses were conducted by SPSS 19.0. Path analysis was used to evaluate the fitness of the hypothesised model in explaining the associations among self-efficacy, affect and quality of life. It was conducted by M-plus version 5.2 (Muthen & Muthen 2008) with observed variables and maximum likelihood estimation method. Model goodness-of-fit was evaluated using several indices. A Satorra–Bentler scaled chi-square value with a non-significant P-value (Kelloway 1998), a root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) with values 0.08 or less (Steiger 1990), and a comparative fit index (CFI) and Tucker–Lewis index (TLI) with values 0.90 or above indicate a satisfactory fit in the model (Hu & Bentler 1999). Positive affect Negative affect –0.37 Figure 2. Final model with standardised path coefficients. All paths significant at P < 0.001. Table 1. As hypothesised, self-efficacy was associated with quality of life (r = 0.53, P < 0.01), positive affect (r = 0.45, P < 0.01) and negative affect (r = −0.35, P < 0.01). Positive affect (r = 0.45, P < 0.01) and negative affect (r = −0.52, P < 0.01) were also significantly correlated with quality of life. Path analysis Path analysis was conducted to examine the fitness of the proposed model which hypothesised that affect mediated the relationship between self-efficacy and quality of life. This hypothesised model showed a good fit in predicting quality of life [χ2 (1) = 1.935, P > 0.05, CFI = 0.996; TLI = 0.975; RMSEA = 0.063] (Fig. 2). All paths were statistically significant (P < 0.001). The associations among the variables remained largely the same even after controlling for the potential influence of age, cancer stage and time since diagnosis on quality of life (significant demographic variables correlated with quality of life). The model thus supported the direct effect of self-efficacy on quality of life, and the indirect effects of self-efficacy on quality of life © 2013 John Wiley & Sons Ltd Quality of life among Chinese cancer survivors through positive affect and negative affect. Specifically, the indirect effects from self-efficacy to quality of life via positive affect (β = 0.102, P < 0.001) and via negative affect (β = 0.129, P < 0.001), were statistically significant. In the model, self-efficacy explained 19.7% and 12.1% of variances of positive affect and negative affect. All paths explained 44.2% of variances of quality of life. DISCUSSION This study contributes to the literature by exploring affect as a mediator to explain the relationship between selfefficacy and quality of life among Chinese cancer patients. First, we found that self-efficacy was positively associated with quality of life among Chinese cancer survivors, in line with Western findings (Hochhausen et al. 2007; Howsepian & Merluzzi 2009; Mosher et al. 2010). The beneficial role of self-efficacy to Chinese cancer survivors’ well-being is supported. Second, we found a significant indirect effect of self-efficacy on quality of life through both positive affect and negative affect. Qualitative studies conducted among Chinese cancer survivors have shown that Chinese people believe that maintenance of positive states of mind can help to deal with fear of recurrence and promote cancer recovery (Simpson 2005; Hou et al. 2009; Cheng et al. 2013). Consistent with previous studies on affect and health outcomes (Howell et al. 2007; Xu & Roberts 2010; Diener & Chan 2011), our findings suggest that greater self-efficacy was associated with more positive affect and less negative affect, which in turn was associated with better quality of life. The Broaden-andBuild Theory (Fredrickson 2001) may provide an explanation for the findings. It suggests that increasing positive affect and reducing negative affect could broaden people’s thought-action repertoires and build resources for coping, which could in turn facilitate better health outcomes. We have examined the mediating role of affect between selfefficacy and quality of life among cancer patients as the first step. We thus recommend future research to take the next step by examining if the influence of positive affect and negative affect on quality of life is mediated by people’s coping resources in the context of cancer adaptation. In addition to affect, other mediators may be at play between self-efficacy and quality of life among cancer survivors. Different mediators have been proposed in previous studies among cancer patients. One study showed that the effect of self-efficacy on quality of life was partially mediated by perceived stress among 60 cancer survivors in Israel (Kreitler et al. 2007). Higher self-efficacy was associated with lower perceived stress, which in turn promoted better quality of life. Another study showed that the effect © 2013 John Wiley & Sons Ltd of self-efficacy on benefit finding was mediated by positive social comparison among 106 post-surgery cancer patients in Germany (Schulz & Mohamed 2004). A longitudinal study conducted among patients receiving breast cancer surgery in Hong Kong showed that the relationship between self-efficacy and adjustment outcomes was mediated by expectancy-outcome incongruence, which is the cognitive judgement about congruence between expected and perceived outcome of the surgery. Higher general self-efficacy may be associated with expectancy-outcome incongruence. This in turn led to poorer adjustment outcomes at 1-month follow-up (Lam & Fielding 2007). Integrating these findings with ours, it implies that selfefficacy may influence quality of life through both affective pathways and cognitive-behavioural pathways. Future studies should explore how these factors may work together to produce different effects on cancer adjustment. This study shows that affect explained the link between self-efficacy and quality of life. While other studies propose such a link is mediated through cognitive or behavioural pathways, future research can also compare the relative prominence of affective, behavioural and cognitive pathways in mediating the influence of different aspects of self-efficacy (e.g. symptom management, information and support seeking) on quality of life. Our findings contradict those of a previous study among Chinese breast cancer patients in Hong Kong, showing that self-efficacy may facilitate unrealistic expectancies about postsurgical outcomes. Potential discrepancies may be explained by the length of cancer survivorship. Participants in Lam and Fielding’s study were patients who had finished breast cancer surgery within a month of the study, which represents a very different adaptation stage from our sample. In that study, general self-efficacy at very early stages of cancer adaptation may involve an overestimate of personal resources in coping with stressors, which could lead to incongruence between expected and actual outcomes. In contrast, our sample had a high percentage of cancer patients (73.5%) having survived for at least 2 years after diagnosis. They had also undergone different types of treatment (e.g. surgery, chemotherapy, and Traditional Chinese Medicine) before the study. Due to their experiences living with cancer, it may be easier for our participants to realistically reflect their personal resources when answering questions related to self-efficacy for coping with cancer. Self-efficacy measured at a later stage of cancer adaptation may lead to less incongruence between expected and actual outcomes. To further validate this claim, future studies should explore if the effect of self-efficacy and other mediators differ at different stages of cancer adaptation. 153 YEUNG & LU This study was subject to several limitations. First, it was a cross-sectional study, for which a causal relationship could not be inferred. Future studies should investigate the temporal and causal relationships among selfefficacy, affect, and quality of life with longitudinal and experimental designs. Second, the non-random sample and self-selection bias in participation might compromise the generalisability of the findings. Despite these limitations, our findings provide important practical implications. Future interventions should be designed to enhance cancer survivors’ self-efficacy and positive affect, which in turn help to increase Chinese cancer survivors’ quality of life. Self-care skills training sessions are believed to be useful in increasing self-efficacy for adaptation to cancer in affective and behavioural aspects. The self-efficacy REFERENCES Bandura A. (1977) Self-efficacy towards a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychological Review 84, 191–215. Bandura A. (1997) Self-efficacy: The Exercise of Control. Freeman, New York, USA. Billings D.W., Folkman S., Acree M. & Moskowitz J.T. (2000) Coping and physical health during caregiving: the roles of positive and negative affect. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 79, 131–142. Bower J.E., Meyerowitz B.E., Desmond K.A., Rowland J.H. & Ganz P.A. (2005) Perceptions of positive meaning and vulnerability following breast cancer: predictors and outcomes among longterm breast cancer survivors. Annals of Behavioral Medicine 29, 236–245. Bradburn N. (1969) The Structure of Psychological Well-being. Aldine, Chicago, IL, USA. Campbell L.C., Keefe F.J., McKee D.C., Edwards C.L., Herman S.H., Johnson L.E., Colvin M., McBride C.M. & Donattuci C.F. (2004) Prostate cancer in African Americans: relationship of patient and partner self-efficacy to quality of life. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management 28, 433–444. Chan W., Epstein I., Reese D. & Chan C.L.W. (2009) Family predictors of psychosocial outcomes among Hong Kong Chinese cancer patients in palliative care: living and dying with the ‘support paradox’. Social Work in Health Care 48, 519–532. Cheng H., Sit J.W.H., Twinn S.F., Cheng K.K.F. & Thorne S. (2013) Coping with breast cancer survivorship in Chinese women: the role of fatalism or fatalistic 154 scale we used captures multiple domains in adjustment, such as efficacy to maintain independence and positive attitude, seek medical information and social support, manage stress, cope with treatment side-effects, and regulate affect. It may provide a comprehensive tool for evaluating patients’ self-efficacy in multiple aspects of self-care tasks. This study shows that self-efficacy is positively associated with quality of life among Chinese cancer survivors. It also supports the mediating role of affect in explaining the association between mental adjustment styles and quality of life. Future interventions should aim to increase cancer survivors’ positive affect and self-efficacy, which in turn could improve quality of life for better cancer survivorship. voluntarism. Cancer Nursing 36:236–244. doi: 10.1097/NCC.0b013e31826542b2. Cunningham A.J., Lockwood G.A. & Cunningham J.A. (1991) A relationship between perceived self-efficacy and quality of life in cancer patients. Patient Education and Counseling 17, 71–78. Dempster A., Laird N. & Rubin D. (1977) Maximum likelihood from incomplete data via the EM algorithm. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society Series B – Statistical Methodology 39, 1–38. Deno M., Tashiro M., Miyashita M., Asakage T., Takahashi K., Saito K., Busujima Y., Mori Y., Saito H. & Ichikawa Y. (2012) The mediating effects of social support and self-efficacy on the relationship between social distress and emotional distress in head and neck cancer outpatients with facial disfigurement. Psycho-oncology 21, 144–152. Diener E. & Chan M.Y. (2011) Happy people live longer: subjective well-being contributes to health and longevity. Applied Psychology: Health and WellBeing 3, 1–43. Ferrell B.R., Dow K.H. & Grant M. (1995) Measurement of the quality of life in cancer survivors. Quality of Life Research 4, 523–531. Folkman S. (1997) Positive psychological states and coping with severe stress. Social Science and Medicine 45, 1207– 1221. Fredrickson B.L. (2001) The role of positive emotions in positive psychology: the Broaden-and-Build Theory of positive emotions. The American Psychologist 56, 218–226. Fredrickson B.L. & Joiner T. (2002) Positive emotions trigger upward spirals toward emotional well-being. Psychological Science 13, 172–175. Heitzmann C.A., Merluzzi T.V., Jean-Pierre P., Roscoe J.A., Kirsh K.L. & Passik S.D. (2011) Assessing self-efficacy for coping with cancer: development and psychometric analysis of the brief version of the Cancer Behavior Inventory (CBI-B). Psycho-oncology 20, 302–312. Hirai K., Suzuki Y., Tsuneto S., Ikenaga M., Hosaka T. & Kashiwagi T. (2002) A structural model of the relationships among self-efficacy, psychological adjustment, and physical condition in Japanese advanced cancer patients. Psycho-oncology 11, 221–229. Hochhausen N., Altmaier E.M., McQuellon R., Davies S.M., Papadopolous E., Carter S. & Henslee-Downee J. (2007) Social support, optimism, and self-efficacy predict physical and emotional wellbeing after bone marrow transplantation. Journal of Psychosocial Oncology 25, 87–101. Hou W.K., Lam W.W.T. & Fielding R. (2009) Adaptation process and psychosocial resources of Chinese colorectal cancer patients undergoing adjuvant treatment: a qualitative analysis. Psychooncology 18, 936–944. Howell R.T., Kern M.L. & Lyubomirsky S. (2007) Health benefits: meta-analytically determining the impact of well-being on objective health outcomes. Health Psychology Review 1, 83–136. Howsepian B.A. & Merluzzi T.V. (2009) Religious beliefs, social support, selfefficacy and adjustment to cancer. Psycho-oncology 18, 1069–1079. Hu L.T. & Bentler P.M. (1999) Cut-off criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling 6, 1–55. © 2013 John Wiley & Sons Ltd Quality of life among Chinese cancer survivors Johnston-Brooks C.H., Lewis M.A. & Garg S. (2002) Self-efficacy impacts self-care and HbA1c in young adults with Type I diabetes. Psychosomatic Medicine 64, 43–51. Karademas C.K. (2006) Self-efficacy, social support and well-being: the mediating role of optimism. Personality and Individual Differences 40, 1281–1290. Kelloway E.K. (1998) Assessing model fit. In: Using LISREL for Structural Equation Modeling: A Researcher’s Guide (ed. Kelloway E.K.), pp. 23–40. Sage Publication, Thousand Oaks, CA, USA. Kershaw T.S., Mood D.W., Newth G., Ronis D.L., Sanda M.G., Vaishampayan U. & Northouse L.L. (2008) Longitudinal analysis of a model to predict quality of life in prostate cancer patients and their spouses. Annals of Behavioral Medicine 36, 117–128. Kessler T.A. (2002) Contextual variables, emotional state, and current and expected quality of life in breast cancer survivors. Oncology Nursing Forum 29, 1109–1116. Kohno Y., Maruyama M., Matsuoka Y., Matsushita T., Koeda M. & Matsushima E. (2010) Relationship of psychological characteristics and self-efficacy in gastrointestinal cancer survivors. Psycho-oncology 19, 71–76. Kreitler S., Peleg D. & Ehrenfeld M. (2007) Stress, self-efficacy and quality of life © 2013 John Wiley & Sons Ltd in cancer patients. Psycho-oncology 16, 329–341. Lam W.W.T. & Fielding R. (2007) Is selfefficacy a predictor of short-term postsurgical adjustment among Chinese women with breast cancer? Psychooncology 16, 651–659. Lev E.L. (1997) Bandura’s theory of selfefficacy: applications to oncology. Research and Theory for Nursing Practice 11, 21–37. Liu J., Mok E. & Wong T. (2005) Perceptions of supportive communication in Chinese patients with cancer: experiences and expectations. Journal of Advanced Nursing 52, 262–270. Luszcynska A., Sarkar Y. & Knoll N. (2007) Received social support, self-efficacy, and finding benefits in disease as predictors of physical functioning and adherence to antiretroviral therapy. Patient Education and Counseling 66, 37–42. Merluzzi T.V., Nairn R.C., Hedge K., Sanchez M.A.M. & Dunn L. (2001) Selfefficacy for coping with cancer: revision of the cancer behavior inventory (version 2.0). Psycho-oncology 10, 206–217. Mosher C.E., DuHamel K.N., Egert J. & Smith M.Y. (2010) Self-efficacy for coping with cancer in a multiethnic sample of breast cancer patients: associations with barriers to pain management and distress. The Clinical Journal of Pain 26, 227–234. Muthen L.K. & Muthen B.O. (2008) Mplus User’s Guide, 5th edn. Muthen & Muthen, Los Angeles, CA, USA. Schulz U. & Mohamed N.E. (2004) Turning the tide: benefit finding after cancer surgery. Social Science and Medicine 59, 653–662. Simpson P. (2005) Hong Kong families and breast cancer: beliefs and adaptation strategies. Psycho-oncology 14, 671–683. Steiger J.H. (1990) Structural model evaluation and modification: an interval estimation approach. Multivariate Behavioral Research 25, 173–180. Sun L.N.N. & Stewart S.M. (2000) Psychological adjustment to cancer in a collective culture. International Journal of Psychology 33, 177–185. Wong-Kim E., Sun A., Merighi J.R. & Chow E.A. (2005) Understanding qualityof-life issues in Chinese women with breast cancer: a qualitative investigation. Cancer 12 (Suppl. 2), 6–12. Wu H.K., Chau J.P. & Twinn S. (2007) Selfefficacy and quality of life among stoma patients in Hong Kong. Cancer Nursing 30, 186–193. Xu J. & Roberts R.E. (2010) The power of positive emotions: it’s a matter of life or death – subjective well-being and longevity over 28 years in a general population. Health Psychology 29, 9–19. 155