Species and Spec es d Speciation

advertisement

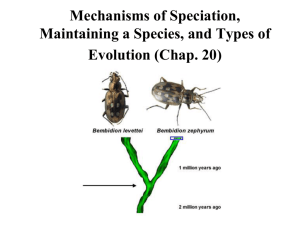

Spec es and Species d Speciation Species are different “kinds” of organisms. S i are the Species th product d t off divergence di off genetic ti lineages. li When one genetic lineage becomes two each lineage can have an independent evolutionary future. The difference between species can be slight or dramatic. Biologists differ in their concept of species. The difference in concepts used can depend on the group of organisms studied or on the goal of the researcher who studies them. • Biological species concept – a population or groups of populations l ti that th t are actually t ll or potentially t ti ll interbreeding i t b di andd reproductively isolated from other populations. • Evolutionary species concept – a single lineage of populations that maintains an identity separate from other such lineages and which has its own evolutionary tendencies and historical fate. • Phylogenetic species concept – the smallest monophyletic group distinguished by a synapomorphy. • Recognition species concept – the most inclusive population of individual organisms that share a common fertilization system Ultimately, the idea of a species is a human construct that allows us to communicate about different forms of life. Deciding what populations constitute a species can be difficult because reproductive isolation or other species criteria can can’tt always be easily assessed. In practice, species are often identified by consistent differences in one or more characteristics. This is the phenetic species concept. p Asexual organisms g can onlyy be designated g pphenetically. y It is assumed that consistent differences are associated with reproductive isolation. isolation If this is disproven, then the species d i ti can be designation b revised. Even though the biological species concept can be problematic in practice, and it only applies to sexually reproducing organisms, it is the species concept that is most often used by evolutionary biologists because it seems to correspond to what occurs in nature. Forms that are reproductively isolated maintain separate identities. identities Reproductive isolation – the restriction of ggenetic exchange g between groups even when those groups are sympatric (live in the same region) region). The restriction is often not absolute but sufficiently restrictive so that each group maintains a separate genetic identity. A single species can have a range of forms but so long as the forms are not reproductively isolated, there is the potential for them to exchange genes and share the same evolutionary fate. Because the divergence of lineages to the point of reproductive isolation can be a long process, many lineages may be only partially isolated, or isolated in some areas but not in others. The divergence of lineages can be gradual and their genetic separation may not become complete. This can result lt in i hybrid h b id zones. If those zones are narrow, and stable, they may be called different species Members of one species often vary geographically. Intermediate forms often exist and show evidence of genetic exchange. Sometimes geographic variants of a species are called subspecies. p Some species, are difficult to distinguish using external and easily observable features, features but are reproductively isolated. isolated Such cases are called “sibling species.” Sibling species Sibli i show h that h appearance is i not the critical criterion for different species. Some plants, classified as different species broadly hybridize. Populations, subspecies, and reproductively isolated species have gradations of genetic differences. differences The biological species concept can only be applied to organisms that are sexual and outcrossing. Asexual forms may be called different species, but a different criterion must be used. For asexuals two forms are called different species if they differ in some consistent way. In spite of difficulties, the biological species concept is broadly applicable. pp Many y closelyy related species p are reproductively p y isolated. There are many barriers to gene flow that result in reproductive isolation. Barriers are classified as premating or postmating. postmating Reproductive p isolation is due to barriers to ggene exchange g I. Premating barriers – keep species from mating II. Postmating barriers – mating occurs but gene flow between species does not occur because of A. Prezygotic barriers – mating occurs but zygotes are not formed B. Postzygotic barriers – zygotes are formed but have reduced fitness Premating barriers 1. Ecological differences result in potential mates not meeting a. Temporal T l (timing) (ti i ) differences diff b. Habitat differences 2. Potential mates meet but do not mate a. Behavioral differences b. Pollinator differences Prematingg barriers 1. Ecological differences result in potential mates not meeting a Temporal (timing) differences a. b. Habitat differences 2. Potential mates meet but do not mate a. Behavioral h i l differences diff b. Pollinator differences Postmating, prezygotic barriers A Mechanical A. M h i l barriers b i – poor fit fi off mating i structures results l in ineffective gamete transfer B. Copulatory p y behavioral barriers – matingg occurs but there is no fertilization because of behavioral differences or lack of proper stimulation C Gametic isolation – mating occurs but gametes are C. incompatible (lack proper enzymes, attractants, etc.) Postmating, postzygotic barriers A. Ecological inviability – the hybrid is not fit in either parents’ niche B. Behavioral sterility – the hybrid is unable to attract either parental species as a mate C. Hybrid inviability – the hybrid has reduced survival due to developmental problems D. Hybrid sterility – the hybrid has reduced ability to form viable gametes Hybrid sterility is most often seen in the heterogametic sex – males in mammals and insects – females in birds and butterflies butterflies. This is called “Haldane’s Rule.” Hybrid problems may not develop in the F1 offspring, but crosses among the F1 and backcrosses to the parental species may produce inviable or sterile offspring . This is called “F2 breakdown.” Coyne and Orr used genetic distance to estimate time of divergence of many species pairs of Drosophila and compared their degree of prezygotic isolation and postzygotic isolation with their divergence time. The h strengthh off isolation i l i increases with time – for both types yp of barriers Full reproductive isolation evolves with variable amounts of divergence (0.3 to 0.5) ~1.5 to 3 million years Among recently diverged forms the strength of prezygotic isolation is greater than the strength of postzygotic isolation. isolation For one species to become two, separate populations of the same species must become reproductively isolated. For reproductive isolation to evolve, some change must occur in one or both lineages in ecology, behavior, physiology, bi h i biochemistry, or genetic i system that h makes k them h reproductively incompatible. How one lineage can become p with its closest relative lineage g is the keyy incompatible question of how new species are formed. How can an allele that makes an individual reproductively incompatible p with its relatives increase in frequency q y in a population? Dobzhansky-Muller Incompatibility Allele A1 increases in one population due to fitness advantages or due to genetic drift. Allele B1 increases in one population due to fitness advantages or due to genetic drift. Alleles A1 and B1 are incompatible with each other and hybrids (A1A2B1B2) are either not formed or have low fitness when the populations come into contact. Speciation can involve the gradual development of reproductive isolation, or in the case of some types of chromosomal change, be nearly instantaneous Gradual G d l speciation i i can be b defined d fi d through h h the h geography h off the populations involved. Allopatric speciation is the evolution of reproductive barriers between populations that are geographically separated. When allopatric populations expand their ranges g and come into contact theyy might g • interbreed and blend to become a single continuous species • interbreed in the region of contact and form a stable hybrid zone • not interbreed due to some barrier to reproduction that evolved while they were allopatric ll t i The evidence for allopatric p differentiation of geographically separated populations is clear Peripheral isolation (peripatric speciation) - the development of reproductive isolation in small marginal populations of a species. species There are many examples of new species that arise from single populations of a widespread species. Moths of the genus Greya This mayy not be different from simple p allopatric speciation or it may involve some component of genetic drift. Mayr hypothesized that founder populations, because they are small may have reduced genetic variation and low fitness due to small, genetic drift. Drift may increase the frequency of alleles that were rare in the ancestral population. In such a situation, selection l ti for f new combinations bi ti off alleles ll l that th t are compatible tibl with ith the newly fixed alleles may occur and allow increased fitness in the new conditions. A possible result is a reorganization of the genome that makes it incompatible with the ancestral population. Mayr envisioned a fitness topography where the founder population went through a low fitness valley due to drift and after selection and reorganization, the population evolved to a new fitness peak that is i incompatible tibl with ith the th ancestral t l population. In theory, natural selection can result in the evolution of barriers to reproduction d i while hil the h populations l i are allopatric. ll i Alternatively, selection can increase the degree of prezygotic isolation among populations that have partial postzygotic isolation. If the th hybrid h b id off two t forms f has h lower fitness than nonhybrid offspring, any variation in a prezygotic barrier in the two forms may result in selection that increases the frequency of the alleles that are the basis for the barrier. The preference may be for any prezygotic barrier - ecological or behavioral. If the h fi fitness off the h hybrid h b id is i not reduced d d (there ( h is i no postzygotic i isolation), then there will be no selection to reinforce the pprezygotic yg barrier and the ppopulations p will likelyy blend. Reproductive character displacement - species are more similar i il in i allopatry ll than h in i sympatry. It can be produced by any selection for prezygotic differences. p for resources in the zone It can also the pproduct of competition of sympatry. In tree frogs, where partial postzygotic i isolation i l i is i known, k song characteristics are most similar between allopatric p populations and most different between sympatric populations. Females of each species show greater preference for males of their own species p when theyy come from populations that are sympatric with the other species. The strength of preference decreases with the volume of the call of the other species. species Prezygotic isolation is stronger among sympatric forms than among allopatric forms. There is some evidence that postzygotic isolation can select for prezygotic ti differences diff between b t species. i Parapatric speciation - the origin of new species over the former range of the ancestral species. species The populations can only diverge if there is relatively strong selection across the geographic range of the species. Often due to an ecological cline. A stable hybrid zone may result if there is moderate selection against g the hybrids. y Complete divergence can occur if there is strong selection against the hybrids - as in reinforcement of reproductive isolation in formerly allopatric populations. Ring species are a special case of parapatric speciation over ggeographic g p range. g The ends of the range are geographically close to each other but genetic exchange can only occur through h h a great distance. di The ends of the range g are more different from each other genetically than any of the intervening populations. The pattern produced by parapatric speciation and the reestablishment of contact of formerly allopatric populations is difficult to distinguish. The best case for parapatric speciation i in is i populations l i off plants l on contaminated soils. Adaptation to contaminated soils results in hybrids that are unfit in either environment. Selection against hybrids has resulted in divergence in flowering time in adjacent populations l i andd selection l i for f self lf pollination in the population on the contaminated soil. Anthoxanthum odoratum - a grass Sympatric speciation - the development of reproductive isolation between forms of a species that live entirely in the same geographic region. Strong disruptive selection for habitat differences or differences in reproductive timing may result in divergent phenotypes that produce hybrids that are unfit for the same environment for which th parental the t l types t are well ll suited. it d Potential scenario: Two homozygous genotypes A1A1 and A2A2 are well suited to different host plants and their hybrid A1A2 has low fitness on both host plants. If another gene is introduced that produces a difference in mating behavior that is correlated with the host plant it will reinforce mating among like genotypes and potentially lead to complete divergence. Apple maggot flies may be a case of the beginning stages of sympatric speciation. speciation The apple race emerges early and parasitizes apples. apples The Haw race emerges late and parasitizes haws. Any mating between a late apple fly and an early haw fly will pproduce hybrids y with an intermediate emergence time with fewer opportunities to parasitize apples. apples Those that avoid mating with the other race will produce offspring g times appropriate pp p for apples pp or haws. with emergence The two races already show some preferences in mating for members of their own race. Speciation by polyploidy and recombination Hybrid organisms receive two different sets of chromosomes, one from each parent species. They are usually sterile because differences in gene arrangements among chromosomes results in improper synapsis and aneuploid gametes. Duplication of whole sets of chromosomes ( ll l id ) (allopolypoidy) may result in ggametes that can produce balanced sets of chromosomes. chromosomes Allopolyploids with a diploid number of sets of chromosomes from each parent (2NA + 2NB) produce gametes that are euploid with one set of chromosomes from each parent (NA + NB). Such organisms g are ppotentially y interfertile or self-fertile but theyy can’t produce fertile offspring in backcrosses with either parent species. Gamete (NA + NB) combined with gamete (NA) produces an allotriploid (2NA + NB) that produces unbalanced sets of genes in gametes. Thus, allopolyploids are reproductively isolated from each of their pparent species. p Theyy can onlyy reproduce p with other allopolyploids or through self-fertilization. They are new species as soon as they are formed. Many species of plants and some animals are polyploid. At least 50% of all flowering plants are polyploid. Read: Evolutionary History of Humans Classically there have b been two hhypotheses h f for the evolution of humans, the multiregional g hypothesis - modern Homo sapiens evolved simultaneously throughout the old world from archaic Homo sapiens i with ith exchange h off genetic information by gene flow and the out-of-Africa out of Africa hypothesis - modern humans evolved in Africa and moved out replacing previously widelyy dispersed p archaic humans Mitochondrial DNA analysis of modern humans suggests that Asian, European, Australian and Indonesian populations all share a common ancestor that ddispersed spe sed from o Africa c about bou 80,000 years ago. Multiple dispersals out of central Asia appear to account for European populations. populations Read: Did Humans and Neanderthals Interbreed?