Document 14328432

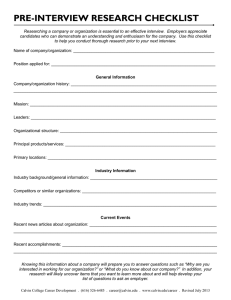

advertisement