Identity as a Cybernetic Process, Construct and Project

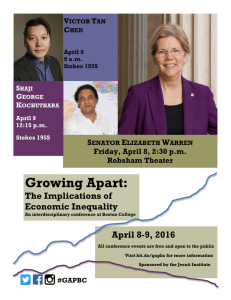

advertisement