Skilled Immigration and the Employment Structures of U.S. Firms September, 2014

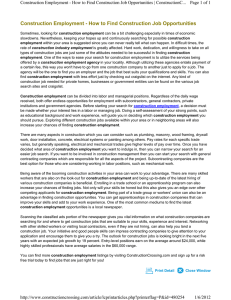

advertisement