Confessional Commitment and Academic Freedom at Calvin College

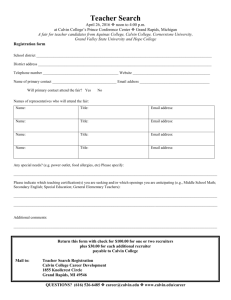

advertisement