RIETI International Seminar Handout Speaker: Prof. Elhanan HELPMAN

Research Institute of Economy, Trade and Industry (RIETI)

RIETI International Seminar

Handout

April 4, 2014

Speaker: Prof. Elhanan HELPMAN http://www.rieti.go.jp/jp/index.html

Matching and Sorting in the Global Economy

Gene Grossman Elhanan Helpman Philipp Kircher

Princeton University Harvard University University of Edinburgh

April 2014

April 2014 1 / 26 Grossman, Helpman and Kircher

Motivation

Observations about worker heterogeneity :

Grossman, Helpman and Kircher

April 2014 2 / 26

1

2

3

4

Much within-industry wage inequality: changes in income distribution re‡ect more than changes in relative rewards to broad factor classes (Helpman et al.

2013)

Distribution of factor “quality” (diversity) is a source of comparative advantage (Bombardini et al. 2013)

Positive assortative matching (PAM) between workers and …rms within industries

Exporter wage premium, but trade/openness a¤ects degree of PAM

Motivation

Observations about worker heterogeneity :

1 Much within-industry wage inequality: changes in income distribution re‡ect more than changes in relative rewards to broad factor classes (Helpman et al.

2013)

Grossman, Helpman and Kircher

April 2014 2 / 26

2

3

4

Distribution of factor “quality” (diversity) is a source of comparative advantage (Bombardini et al. 2013)

Positive assortative matching (PAM) between workers and …rms within industries

Exporter wage premium, but trade/openness a¤ects degree of PAM

Motivation

Observations about worker heterogeneity :

1

2

Much within-industry wage inequality: changes in income distribution re‡ect more than changes in relative rewards to broad factor classes (Helpman et al.

2013)

Distribution of factor “quality” (diversity) is a source of comparative advantage (Bombardini et al. 2013)

Grossman, Helpman and Kircher

April 2014 2 / 26

3

4

Positive assortative matching (PAM) between workers and …rms within industries

Exporter wage premium, but trade/openness a¤ects degree of PAM

Motivation

Observations about worker heterogeneity :

1

2

3

Much within-industry wage inequality: changes in income distribution re‡ect more than changes in relative rewards to broad factor classes (Helpman et al.

2013)

Distribution of factor “quality” (diversity) is a source of comparative advantage (Bombardini et al. 2013)

Positive assortative matching (PAM) between workers and …rms within industries

April 2014 2 / 26 Grossman, Helpman and Kircher

4 Exporter wage premium, but trade/openness a¤ects degree of PAM

Motivation

Observations about worker heterogeneity :

1

2

3

4

Much within-industry wage inequality: changes in income distribution re‡ect more than changes in relative rewards to broad factor classes (Helpman et al.

2013)

Distribution of factor “quality” (diversity) is a source of comparative advantage (Bombardini et al. 2013)

Positive assortative matching (PAM) between workers and …rms within industries

Exporter wage premium, but trade/openness a¤ects degree of PAM

Grossman, Helpman and Kircher

April 2014 2 / 26

Motivation

Observations about the distribution of earnings :

Grossman, Helpman and Kircher

April 2014 3 / 26

We study the entire distribution of earnings ; the bottom and the top, which di¤er across countries

2000 2007

5/1 9/5 5/1 9/5

Canada

France #

# "

Germany

2.000

1.736

1.995

1.810

1.561

2.112

1.521

2.093

" # 1.649

1.820

1.783

1.816

Ireland

Japan "

" 1.814

1.892

1.941

1.976

1.592

1.730

1.618

1.774

Korea "

Norway

Sweden

UK # "

U.S.A.

"

1.973

1.881

2.205

2.131

" 1.440

1.495

1.577

1.548

" # 1.402

1.742

1.422

1.721

1.828

1.891

1.826

2.023

2.137

2.240

2.146

2.397

Decile ratios of men’s gross earnings.

Motivation

Observations about the distribution of earnings :

We study the entire distribution of earnings ; the bottom and the top, which di¤er across countries

Grossman, Helpman and Kircher

April 2014 3 / 26

2000 2007

5/1 9/5 5/1 9/5

Canada

France #

# "

Germany

2.000

1.736

1.995

1.810

1.561

2.112

1.521

2.093

" # 1.649

1.820

1.783

1.816

Ireland

Japan "

" 1.814

1.892

1.941

1.976

1.592

1.730

1.618

1.774

Korea "

Norway

Sweden

UK # "

U.S.A.

"

1.973

1.881

2.205

2.131

" 1.440

1.495

1.577

1.548

" # 1.402

1.742

1.422

1.721

1.828

1.891

1.826

2.023

2.137

2.240

2.146

2.397

Decile ratios of men’s gross earnings.

Motivation

Observations about the distribution of earnings :

We study the entire distribution of earnings ; the bottom and the top, which di¤er across countries

2000 2007

5/1 9/5 5/1 9/5

Canada

France #

# "

Germany

2.000

1.736

1.995

1.810

1.561

2.112

1.521

2.093

" # 1.649

1.820

1.783

1.816

1.814

1.892

1.941

1.976

Ireland

Japan "

"

Korea "

Norway "

1.592

1.730

1.618

1.774

1.973

1.881

2.205

2.131

1.440

1.495

1.577

1.548

Sweden

UK # "

U.S.A.

"

" # 1.402

1.742

1.422

1.721

1.828

1.891

1.826

2.023

2.137

2.240

2.146

2.397

Decile ratios of men’s gross earnings.

Grossman, Helpman and Kircher

April 2014 3 / 26

This Paper

Theoretical: Understand interactions between forces of matching and sorting in shaping trade and earnings

Grossman, Helpman and Kircher

April 2014 4 / 26

Captures forces likely to be present in any reasonable model, even if not the only forces present

Uses a factor proportions framework with two heterogeneous inputs

(“workers” and “managers”)

Productivity of unit depends on factor types— with complementarity

Extends the framework to (directed) search and unemployment

Including Ricardo-Viner and Heckscher-Ohlin interactions

This Paper

Theoretical: Understand interactions between forces of matching and sorting in shaping trade and earnings

Captures forces likely to be present in any reasonable model, even if not the only forces present

Grossman, Helpman and Kircher

April 2014 4 / 26

Including Ricardo-Viner and Heckscher-Ohlin interactions

Uses a factor proportions framework with two heterogeneous inputs

(“workers” and “managers”)

Productivity of unit depends on factor types— with complementarity

Extends the framework to (directed) search and unemployment

This Paper

Theoretical: Understand interactions between forces of matching and sorting in shaping trade and earnings

Captures forces likely to be present in any reasonable model, even if not the only forces present

Including Ricardo-Viner and Heckscher-Ohlin interactions

Grossman, Helpman and Kircher

April 2014 4 / 26

Uses a factor proportions framework with two heterogeneous inputs

(“workers” and “managers”)

Productivity of unit depends on factor types— with complementarity

Extends the framework to (directed) search and unemployment

This Paper

Theoretical: Understand interactions between forces of matching and sorting in shaping trade and earnings

Captures forces likely to be present in any reasonable model, even if not the only forces present

Including Ricardo-Viner and Heckscher-Ohlin interactions

Uses a factor proportions framework with two heterogeneous inputs

(“workers” and “managers”)

April 2014 4 / 26 Grossman, Helpman and Kircher

Productivity of unit depends on factor types— with complementarity

Extends the framework to (directed) search and unemployment

This Paper

Theoretical: Understand interactions between forces of matching and sorting in shaping trade and earnings

Captures forces likely to be present in any reasonable model, even if not the only forces present

Including Ricardo-Viner and Heckscher-Ohlin interactions

Uses a factor proportions framework with two heterogeneous inputs

(“workers” and “managers”)

Productivity of unit depends on factor types— with complementarity

April 2014 4 / 26 Grossman, Helpman and Kircher

Extends the framework to (directed) search and unemployment

This Paper

Theoretical: Understand interactions between forces of matching and sorting in shaping trade and earnings

Captures forces likely to be present in any reasonable model, even if not the only forces present

Including Ricardo-Viner and Heckscher-Ohlin interactions

Uses a factor proportions framework with two heterogeneous inputs

(“workers” and “managers”)

Productivity of unit depends on factor types— with complementarity

Extends the framework to (directed) search and unemployment

Grossman, Helpman and Kircher

April 2014 4 / 26

Questions We Address

Sorting of workers and managers to sectors

Grossman, Helpman and Kircher

April 2014 5 / 26

Matching of workers and managers within sectors

Determinants of comparative advantage/pattern of trade (will not discuss today)

E¤ects of trade on (entire) income distribution

E¤ects of trade on distribution of unemployment rates (will not discuss today)

Questions We Address

Sorting of workers and managers to sectors

Matching of workers and managers within sectors

Grossman, Helpman and Kircher

April 2014 5 / 26

Determinants of comparative advantage/pattern of trade (will not discuss today)

E¤ects of trade on (entire) income distribution

E¤ects of trade on distribution of unemployment rates (will not discuss today)

Questions We Address

Sorting of workers and managers to sectors

Matching of workers and managers within sectors

Determinants of comparative advantage/pattern of trade (will not discuss today)

Grossman, Helpman and Kircher

April 2014 5 / 26

E¤ects of trade on (entire) income distribution

E¤ects of trade on distribution of unemployment rates (will not discuss today)

Questions We Address

Sorting of workers and managers to sectors

Matching of workers and managers within sectors

Determinants of comparative advantage/pattern of trade (will not discuss today)

E¤ects of trade on (entire) income distribution

Grossman, Helpman and Kircher

April 2014 5 / 26

E¤ects of trade on distribution of unemployment rates (will not discuss today)

Questions We Address

Sorting of workers and managers to sectors

Matching of workers and managers within sectors

Determinants of comparative advantage/pattern of trade (will not discuss today)

E¤ects of trade on (entire) income distribution

E¤ects of trade on distribution of unemployment rates (will not discuss today)

April 2014 5 / 26 Grossman, Helpman and Kircher

Economic Environment

Country characteristics:

Grossman, Helpman and Kircher

April 2014 6 / 26

Labor:

¯

,

φ

Managers:

L

H ,

( q

φ

L

H

)

( q

H

)

Densities continuous and strictly positive on bounded supports (intervals): S

L

S

H

,

Two industries

Overall CRS in quantities, competitive equilibrium

Primitive technology could give output as function of list of types

But Eeckhout and Kircher (2012) show: No reason for …rm to hire multiple types of workers in Lucas-type model of span of control

To save on notation, write the output in industry i of one manager of type q

H and ` workers of type q

L as x i

=

ψ i

( q

H

, q

L

) ` γ i

Assume

ψ iF

> 0 for i = 1 , 2 ; F = H , L (refer to q as “ability” or “quality”)

Economic Environment

Country characteristics:

Labor:

¯

,

φ

L

( q

L

)

Grossman, Helpman and Kircher

April 2014 6 / 26

Managers:

¯

,

φ

H

( q

H

)

Densities continuous and strictly positive on bounded supports (intervals): S

L

S

H

,

Two industries

Overall CRS in quantities, competitive equilibrium

Primitive technology could give output as function of list of types

But Eeckhout and Kircher (2012) show: No reason for …rm to hire multiple types of workers in Lucas-type model of span of control

To save on notation, write the output in industry i of one manager of type q

H and ` workers of type q

L as x i

=

ψ i

( q

H

, q

L

) ` γ i

Assume

ψ iF

> 0 for i = 1 , 2 ; F = H , L (refer to q as “ability” or “quality”)

Economic Environment

Country characteristics:

Labor:

¯

,

φ

Managers:

L

H ,

( q

φ

L

H

)

( q

H

)

Grossman, Helpman and Kircher

April 2014 6 / 26

Densities continuous and strictly positive on bounded supports (intervals): S

L

,

S

H

Two industries

Overall CRS in quantities, competitive equilibrium

Primitive technology could give output as function of list of types

But Eeckhout and Kircher (2012) show: No reason for …rm to hire multiple types of workers in Lucas-type model of span of control

To save on notation, write the output in industry i of one manager of type q

H and ` workers of type q

L as x i

=

ψ i

( q

H

, q

L

) ` γ i

Assume

ψ iF

> 0 for i = 1 , 2 ; F = H , L (refer to q as “ability” or “quality”)

Economic Environment

Country characteristics:

Labor:

¯

,

φ

Managers:

L

H ,

( q

φ

L

H

)

( q

H

)

Densities continuous and strictly positive on bounded supports (intervals): S

L

S

H

,

Grossman, Helpman and Kircher

April 2014 6 / 26

Two industries

Overall CRS in quantities, competitive equilibrium

Primitive technology could give output as function of list of types

But Eeckhout and Kircher (2012) show: No reason for …rm to hire multiple types of workers in Lucas-type model of span of control

To save on notation, write the output in industry i of one manager of type q

H and ` workers of type q

L as x i

=

ψ i

( q

H

, q

L

) ` γ i

Assume

ψ iF

> 0 for i = 1 , 2 ; F = H , L (refer to q as “ability” or “quality”)

Economic Environment

Country characteristics:

Labor:

¯

,

φ

Managers:

L

H ,

( q

φ

L

H

)

( q

H

)

Densities continuous and strictly positive on bounded supports (intervals): S

L

S

H

,

Two industries

Grossman, Helpman and Kircher

April 2014 6 / 26

Primitive technology could give output as function of list of types

But Eeckhout and Kircher (2012) show: No reason for …rm to hire multiple types of workers in Lucas-type model of span of control

To save on notation, write the output in industry i of one manager of type q

H and ` workers of type q

L as x i

=

ψ i

( q

H

, q

L

) ` γ i

Assume

ψ iF

> 0 for i = 1 , 2 ; F = H , L (refer to q as “ability” or “quality”)

Overall CRS in quantities, competitive equilibrium

Economic Environment

Country characteristics:

Labor:

¯

,

φ

Managers:

L

H ,

( q

φ

L

H

)

( q

H

)

Densities continuous and strictly positive on bounded supports (intervals): S

L

S

H

,

Two industries

Primitive technology could give output as function of list of types

Grossman, Helpman and Kircher

April 2014 6 / 26

But Eeckhout and Kircher (2012) show: No reason for …rm to hire multiple types of workers in Lucas-type model of span of control

To save on notation, write the output in industry i of one manager of type q

H and ` workers of type q

L as x i

=

ψ i

( q

H

, q

L

) ` γ i

Assume

ψ iF

> 0 for i = 1 , 2 ; F = H , L (refer to q as “ability” or “quality”)

Overall CRS in quantities, competitive equilibrium

Economic Environment

Country characteristics:

Labor:

¯

,

φ

Managers:

L

H ,

( q

φ

L

H

)

( q

H

)

Densities continuous and strictly positive on bounded supports (intervals): S

L

S

H

,

Two industries

Primitive technology could give output as function of list of types

But Eeckhout and Kircher (2012) show: No reason for …rm to hire multiple types of workers in Lucas-type model of span of control

Grossman, Helpman and Kircher

April 2014 6 / 26

To save on notation, write the output in industry i of one manager of type q

H and ` workers of type q

L as x i

=

ψ i

( q

H

, q

L

) ` γ i

Assume

ψ iF

> 0 for i = 1 , 2 ; F = H , L (refer to q as “ability” or “quality”)

Overall CRS in quantities, competitive equilibrium

Economic Environment

Country characteristics:

Labor:

¯

,

φ

Managers:

L

H ,

( q

φ

L

H

)

( q

H

)

Densities continuous and strictly positive on bounded supports (intervals): S

L

S

H

,

Two industries

Primitive technology could give output as function of list of types

But Eeckhout and Kircher (2012) show: No reason for …rm to hire multiple types of workers in Lucas-type model of span of control

To save on notation, write the output in industry i of one manager of type q

H and ` workers of type q

L as x i

=

ψ i

( q

H

, q

L

) ` γ i

Grossman, Helpman and Kircher

April 2014 6 / 26

Assume

ψ iF

> 0 for i = 1 , 2 ; F = H , L (refer to q as “ability” or “quality”)

Overall CRS in quantities, competitive equilibrium

Economic Environment

Country characteristics:

Labor:

¯

,

φ

Managers:

L

H ,

( q

φ

L

H

)

( q

H

)

Densities continuous and strictly positive on bounded supports (intervals): S

L

S

H

,

Two industries

Primitive technology could give output as function of list of types

But Eeckhout and Kircher (2012) show: No reason for …rm to hire multiple types of workers in Lucas-type model of span of control

To save on notation, write the output in industry i of one manager of type q

H and ` workers of type q

L as x i

=

ψ i

( q

H

, q

L

) ` γ i

Assume

ψ iF

> 0 for i = 1 , 2 ; F = H , L (refer to q as “ability” or “quality”)

Grossman, Helpman and Kircher

April 2014 6 / 26

Overall CRS in quantities, competitive equilibrium

Economic Environment

Country characteristics:

Labor:

¯

,

φ

Managers:

L

H ,

( q

φ

L

H

)

( q

H

)

Densities continuous and strictly positive on bounded supports (intervals): S

L

S

H

,

Two industries

Primitive technology could give output as function of list of types

But Eeckhout and Kircher (2012) show: No reason for …rm to hire multiple types of workers in Lucas-type model of span of control

To save on notation, write the output in industry i of one manager of type q

H and ` workers of type q

L as x i

=

ψ i

( q

H

, q

L

) ` γ i

Assume

ψ iF

> 0 for i = 1 , 2 ; F = H , L (refer to q as “ability” or “quality”)

Overall CRS in quantities, competitive equilibrium

Grossman, Helpman and Kircher

April 2014 6 / 26

Strictly Log Supermodular Productivity Functions

Assume:

ψ i

( q

H

, q

L

) is strictly increasing, twice continuously di¤erentiable, and strictly log supermodular for i = 1 , 2

Grossman, Helpman and Kircher

April 2014 7 / 26

Implies PAM within sectors

Can have unconnected intervals of managers or workers that sort into a sector

From FOCs : In interior of set of factors allocated to sector i , m ( q

H

)

ψ iL

γ i

ψ i

[ q

H

, m ( q

H

[ q

H

, m ( q

H

)]

)]

=

ε w

[ m ( q

H

)] q

H ψ iH

[

( 1

γ i

)

ψ i q

H

[ q

, m

H

( q

H

)]

, m ( q

H

)]

=

ε r

( q

H

)

Factor market clearing:

Z q

H q

Ha

( 1

γ i r

γ i

( q )

) w [ m ( q )]

φ

H

( q ) dq =

¯

Z m ( q

H

) m ( q

Ha

)

φ

L

[ m ( q )] dq for all q

H

Strictly Log Supermodular Productivity Functions

Assume:

ψ i

( q

H

, q

L

) is strictly increasing, twice continuously di¤erentiable, and strictly log supermodular for i = 1 , 2

Implies PAM within sectors

Grossman, Helpman and Kircher

April 2014 7 / 26

Can have unconnected intervals of managers or workers that sort into a sector

From FOCs : In interior of set of factors allocated to sector i , m ( q

H

)

ψ iL

γ i

ψ i

[ q

H

, m ( q

H

[ q

H

, m ( q

H

)]

)]

=

ε w

[ m ( q

H

)] q

H ψ iH

[

( 1

γ i

)

ψ i q

H

[ q

, m

H

( q

H

)]

, m ( q

H

)]

=

ε r

( q

H

)

Factor market clearing:

Z q

H q

Ha

( 1

γ i r

γ i

( q )

) w [ m ( q )]

φ

H

( q ) dq =

¯

Z m ( q

H

) m ( q

Ha

)

φ

L

[ m ( q )] dq for all q

H

Strictly Log Supermodular Productivity Functions

Assume:

ψ i

( q

H

, q

L

) is strictly increasing, twice continuously di¤erentiable, and strictly log supermodular for i = 1 , 2

Implies PAM within sectors

Can have unconnected intervals of managers or workers that sort into a sector

Grossman, Helpman and Kircher

April 2014 7 / 26

From FOCs : In interior of set of factors allocated to sector i , m ( q

H

)

ψ iL

γ i

ψ i

[ q

H

, m ( q

H

[ q

H

, m ( q

H

)]

)]

=

ε w

[ m ( q

H

)] q

H ψ iH

[

( 1

γ i

)

ψ i q

H

[ q

, m

H

( q

H

)]

, m ( q

H

)]

=

ε r

( q

H

)

Factor market clearing:

Z q

H q

Ha

( 1

γ i r

γ i

( q )

) w [ m ( q )]

φ

H

( q ) dq =

¯

Z m ( q

H

) m ( q

Ha

)

φ

L

[ m ( q )] dq for all q

H

Strictly Log Supermodular Productivity Functions

Assume:

ψ i

( q

H

, q

L

) is strictly increasing, twice continuously di¤erentiable, and strictly log supermodular for i = 1 , 2

Implies PAM within sectors

Can have unconnected intervals of managers or workers that sort into a sector

From FOCs : In interior of set of factors allocated to sector i , m ( q

H

)

ψ iL

γ i

ψ i

[ q

H

, m ( q

H

[ q

H

, m ( q

H

)]

)]

=

ε w

[ m ( q

H

)] q

H ψ iH

[

( 1

γ i

)

ψ i q

H

[ q

, m

H

( q

H

)]

, m ( q

H

)]

=

ε r

( q

H

)

April 2014 7 / 26 Grossman, Helpman and Kircher

Factor market clearing:

Z q

H q

Ha

( 1

γ i r

γ i

( q )

) w [ m ( q )]

φ

H

( q ) dq =

¯

Z m ( q

H

) m ( q

Ha

)

φ

L

[ m ( q )] dq for all q

H

Strictly Log Supermodular Productivity Functions

Assume:

ψ i

( q

H

, q

L

) is strictly increasing, twice continuously di¤erentiable, and strictly log supermodular for i = 1 , 2

Implies PAM within sectors

Can have unconnected intervals of managers or workers that sort into a sector

From FOCs : In interior of set of factors allocated to sector i , m ( q

H

)

ψ iL

γ i

ψ i

[ q

H

, m ( q

H

[ q

H

, m ( q

H

)]

)]

=

ε w

[ m ( q

H

)] q

H ψ iH

[

( 1

γ i

)

ψ i q

H

[ q

, m

H

( q

H

)]

, m ( q

H

)]

=

ε r

( q

H

)

Factor market clearing:

Z q

H q

Ha

( 1

γ i r

γ i

( q )

) w [ m ( q )]

φ

H

( q ) dq =

¯

Z m ( q

H

)

φ

L

[ m ( q )] dq for all q

H m ( q

Ha

)

Grossman, Helpman and Kircher

April 2014 7 / 26

Equilibrium Requirements

Three di¤erential equations for w ( q

L

) , r ( q

H

) , m ( q

H

)

Di¤erentiate factor market clearing condition wrt q

H

:

γ i r ( q

H

)

( 1

γ i

) w [ m ( q

H

)]

φ

H

( q

H

) =

¯

φ

L

[ m ( q

H

)] m

0

( q

H

)

Grossman, Helpman and Kircher

April 2014 8 / 26

Sorting: w

0

[ m ( q

H

)] w [ m ( q

H

)]

= r

0

( q

H

) r ( q

H

)

=

ψ iL

[ q

H

, m ( q

H

)]

γ i ψ i

[ q

H

, m ( q

H

)] q

H ψ iH

[ q

( 1

γ i

)

ψ i

H

[ q

, m

H

,

( q m

H

( q

)]

H

)]

Boundary conditions : depend on sorting pattern

Continuity : w elsewhere)

( ) and r ( ) increasing and continuous at boundaries (and

Slope conditions : At any boundary, slope of w greater than slope to left. Same for slope of r

( q

L

( q

H

) to right of boundary

) .

Equilibrium Requirements

Three di¤erential equations for w ( q

L

) , r ( q

H

) , m ( q

H

)

Di¤erentiate factor market clearing condition wrt q

H

:

γ i r ( q

H

)

( 1

γ i

) w [ m ( q

H

)]

φ

H

( q

H

) =

¯

φ

L

[ m ( q

H

)] m

0

( q

H

)

Sorting: w

0

[ m ( q

H

)] w [ m ( q

H

)]

= r

0

( q

H

) r ( q

H

)

=

ψ iL

[ q

H

, m ( q

H

)]

γ i ψ i

[ q

H

, m ( q

H

)] q

H ψ iH

[ q

( 1

γ i

)

ψ i

H

[ q

, m

H

,

( q m

H

( q

)]

H

)]

Grossman, Helpman and Kircher

April 2014 8 / 26

Boundary conditions : depend on sorting pattern

Continuity : w elsewhere)

( ) and r ( ) increasing and continuous at boundaries (and

Slope conditions : At any boundary, slope of w greater than slope to left. Same for slope of r

( q

L

( q

H

) to right of boundary

) .

Equilibrium Requirements

Three di¤erential equations for w ( q

L

) , r ( q

H

) , m ( q

H

)

Di¤erentiate factor market clearing condition wrt q

H

:

γ i r ( q

H

)

( 1

γ i

) w [ m ( q

H

)]

φ

H

( q

H

) =

¯

φ

L

[ m ( q

H

)] m

0

( q

H

)

Sorting: w

0

[ m ( q

H

)] w [ m ( q

H

)]

= r

0

( q

H

) r ( q

H

)

=

ψ iL

[ q

H

, m ( q

H

)]

γ i ψ i

[ q

H

, m ( q

H

)] q

H ψ iH

[ q

( 1

γ i

)

ψ i

H

[ q

, m

H

,

( q m

H

( q

)]

H

)]

Boundary conditions : depend on sorting pattern

Grossman, Helpman and Kircher

April 2014 8 / 26

Continuity : w elsewhere)

( ) and r ( ) increasing and continuous at boundaries (and

Slope conditions : At any boundary, slope of w greater than slope to left. Same for slope of r

( q

L

( q

H

) to right of boundary

) .

Equilibrium Requirements

Three di¤erential equations for w ( q

L

) , r ( q

H

) , m ( q

H

)

Di¤erentiate factor market clearing condition wrt q

H

:

γ i r ( q

H

)

( 1

γ i

) w [ m ( q

H

)]

φ

H

( q

H

) =

¯

φ

L

[ m ( q

H

)] m

0

( q

H

)

Sorting: w

0

[ m ( q

H

)] w [ m ( q

H

)]

= r

0

( q

H

) r ( q

H

)

=

ψ iL

[ q

H

, m ( q

H

)]

γ i ψ i

[ q

H

, m ( q

H

)] q

H ψ iH

[ q

( 1

γ i

)

ψ i

H

[ q

, m

H

,

( q m

H

( q

)]

H

)]

Boundary conditions : depend on sorting pattern

Continuity : w elsewhere)

( ) and r ( ) increasing and continuous at boundaries (and

Grossman, Helpman and Kircher

April 2014 8 / 26

Slope conditions : At any boundary, slope of w greater than slope to left. Same for slope of r

( q

L

( q

H

) to right of boundary

) .

Equilibrium Requirements

Three di¤erential equations for w ( q

L

) , r ( q

H

) , m ( q

H

)

Di¤erentiate factor market clearing condition wrt q

H

:

γ i r ( q

H

)

( 1

γ i

) w [ m ( q

H

)]

φ

H

( q

H

) =

¯

φ

L

[ m ( q

H

)] m

0

( q

H

)

Sorting: w

0

[ m ( q

H

)] w [ m ( q

H

)]

= r

0

( q

H

) r ( q

H

)

=

ψ iL

[ q

H

, m ( q

H

)]

γ i ψ i

[ q

H

, m ( q

H

)] q

H ψ iH

[ q

( 1

γ i

)

ψ i

H

[ q

, m

H

,

( q m

H

( q

)]

H

)]

Boundary conditions : depend on sorting pattern

Continuity : w elsewhere)

( ) and r ( ) increasing and continuous at boundaries (and

Slope conditions : At any boundary, slope of w greater than slope to left. Same for slope of r

( q

L

( q

H

) to right of boundary

) .

Grossman, Helpman and Kircher

April 2014 8 / 26

Wage Inequality

From the di¤erential equation for wages: w q

00

L w q

0

L

= exp

"

Z q 0

L q 00

L

ψ iL m

ψ i

[ m 1

1

( z ) , z

( z ) , z ] dz

# for q

0

L

, q

00

L

2 Q int iL

Grossman, Helpman and Kircher

April 2014 9 / 26

Log supermodularity implies that better matches for workers raise wage inequality

Similarly for salaries

Wage Inequality

From the di¤erential equation for wages: w q

00

L w q

0

L

= exp

"

Z q 0

L q 00

L

ψ iL m

ψ i

[ m 1

1

( z ) , z

( z ) , z ] dz

# for q

0

L

, q

00

L

2 Q int iL

Log supermodularity implies that better matches for workers raise wage inequality

April 2014 9 / 26 Grossman, Helpman and Kircher

Similarly for salaries

Wage Inequality

From the di¤erential equation for wages: w q

00

L w q

0

L

= exp

"

Z q 0

L q 00

L

ψ iL m

ψ i

[ m 1

1

( z ) , z

( z ) , z ] dz

# for q

0

L

, q

00

L

2 Q int iL

Log supermodularity implies that better matches for workers raise wage inequality

Similarly for salaries

April 2014 9 / 26 Grossman, Helpman and Kircher

Sorting I

If

ψ

1 L

( q

H min

, q

L

)

γ

1

ψ

1

( q

H min

, q

L

)

>

ψ

2 L

( q

H max

, q

L

)

γ

2

ψ

2

( q

H max

, q

L

) for all q

L

2 S

L then high-ability workers are employed in sector 1 and low-ability workers are employed in sector 2, for some q

L

Grossman, Helpman and Kircher

April 2014 10 / 26

Under this su¢ cient condition, the incentives for high-ability workers to sort to sector 1 does not depend on the sorting of managers

Analogous condition for sorting of managers (better managers might go to sector 1 or sector 2)

If both conditions satis…ed, have “threshold” equilibrium: either HH / LL or

HL / LH

Sorting I

If

ψ

1 L

( q

H min

, q

L

)

γ

1

ψ

1

( q

H min

, q

L

)

>

ψ

2 L

( q

H max

, q

L

)

γ

2

ψ

2

( q

H max

, q

L

) for all q

L

2 S

L then high-ability workers are employed in sector 1 and low-ability workers are employed in sector 2, for some q

L

Under this su¢ cient condition, the incentives for high-ability workers to sort to sector 1 does not depend on the sorting of managers

Grossman, Helpman and Kircher

April 2014 10 / 26

Analogous condition for sorting of managers (better managers might go to sector 1 or sector 2)

If both conditions satis…ed, have “threshold” equilibrium: either HH / LL or

HL / LH

Sorting I

If

ψ

1 L

( q

H min

, q

L

)

γ

1

ψ

1

( q

H min

, q

L

)

>

ψ

2 L

( q

H max

, q

L

)

γ

2

ψ

2

( q

H max

, q

L

) for all q

L

2 S

L then high-ability workers are employed in sector 1 and low-ability workers are employed in sector 2, for some q

L

Under this su¢ cient condition, the incentives for high-ability workers to sort to sector 1 does not depend on the sorting of managers

Analogous condition for sorting of managers (better managers might go to sector 1 or sector 2)

Grossman, Helpman and Kircher

April 2014 10 / 26

If both conditions satis…ed, have “threshold” equilibrium: either HH / LL or

HL / LH

Sorting I

If

ψ

1 L

( q

H min

, q

L

)

γ

1

ψ

1

( q

H min

, q

L

)

>

ψ

2 L

( q

H max

, q

L

)

γ

2

ψ

2

( q

H max

, q

L

) for all q

L

2 S

L then high-ability workers are employed in sector 1 and low-ability workers are employed in sector 2, for some q

L

Under this su¢ cient condition, the incentives for high-ability workers to sort to sector 1 does not depend on the sorting of managers

Analogous condition for sorting of managers (better managers might go to sector 1 or sector 2)

If both conditions satis…ed, have “threshold” equilibrium: either HH / LL or

HL / LH

Grossman, Helpman and Kircher

April 2014 10 / 26

An Equilibrium with HL/LH Sorting q

H q

H max sector 2 q *

H q

H min q

L min

Grossman, Helpman and Kircher sector 1 q *

L

q

L max q

L

April 2014 11 / 26

Sorting II: Su¢ cient Condition for HH/LL

Suppose that:

ψ

1 L

( q

H

, q

L

)

γ 1 ψ

1

( q

H

, q

L

)

>

ψ

2 L

γ 2 ψ

2

( q

H

, q

L

)

( q

H

, q

L

) for all q

H

2 S

H

, q

L

2 S

L

.

Grossman, Helpman and Kircher

April 2014 12 / 26 and (!!!)

ψ

1 H

( q

H

( 1

γ

1

)

ψ

1

, q

L

)

( q

H

, q

L

)

>

ψ

2 H

( q

H

( 1

γ

2

)

ψ

2

, q

L

)

( q

H

, q

L

) for all q

H

2 S

H

, q

L

2 S

L

,

Then high-ability managers and workers are employed in sector 1 and low-ability managers and workers are employed in sector 2, for some pair of cut-points, q

H and q

L

.

Sorting II: Su¢ cient Condition for HH/LL

Suppose that:

ψ

1 L

( q

H

, q

L

)

γ 1 ψ

1

( q

H

, q

L

)

>

ψ

2 L

γ 2 ψ

2

( q

H

, q

L

)

( q

H

, q

L

) for all q

H

2 S

H

, q

L

2 S

L

.

and (!!!)

Grossman, Helpman and Kircher

April 2014 12 / 26

ψ

1 H

( q

H

( 1

γ

1

)

ψ

1

, q

L

)

( q

H

, q

L

)

>

ψ

2 H

( q

H

( 1

γ

2

)

ψ

2

, q

L

)

( q

H

, q

L

) for all q

H

2 S

H

, q

L

2 S

L

,

Then high-ability managers and workers are employed in sector 1 and low-ability managers and workers are employed in sector 2, for some pair of cut-points, q

H and q

L

.

Sorting II: Su¢ cient Condition for HH/LL

Suppose that:

ψ

1 L

( q

H

, q

L

)

γ 1 ψ

1

( q

H

, q

L

)

>

ψ

2 L

γ 2 ψ

2

( q

H

, q

L

)

( q

H

, q

L

) for all q

H

2 S

H

, q

L

2 S

L

.

and (!!!)

ψ

1 H

( q

H

( 1

γ

1

)

ψ

1

, q

L

)

( q

H

, q

L

)

>

ψ

2 H

( q

H

( 1

γ

2

)

ψ

2

, q

L

)

( q

H

, q

L

) for all q

H

2 S

H

, q

L

2 S

L

,

Then high-ability managers and workers are employed in sector 1 and low-ability managers and workers are employed in sector 2, for some pair of cut-points, q

H and q

L

.

Grossman, Helpman and Kircher

April 2014 12 / 26

An Equilibrium with HH/LL Sorting q

H max q

H q

H

* q

H min q

L min sector 2 q

L

* sector 1 q

L max q

L

Grossman, Helpman and Kircher

April 2014 13 / 26

Sorting III: Sorting Reversals

1.1

1.09

1.08

1.07

1.06

1.05

1.04

1.03

1.02

1.01

1

1 1.1

1.2

1.3

1.4

1.5

q

L

1.6

1.7

1.8

Sector 1

Sector 2

1.9

2

Grossman, Helpman and Kircher

April 2014 14 / 26

Sweden 2004

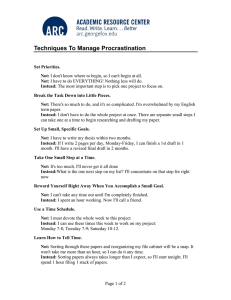

Figure: Variation across manufacturing industries of log mean salary of managers and log mean wage of workers in Sweden: 2004. Source: private communication, Anders

Akerman.

Grossman, Helpman and Kircher

April 2014 15 / 26

Brazil 1994

Figure: Variation across manufacturing industries of log mean salary of managers and log mean wage of workers in Brazil: 1994. Source: own calculations.

Grossman, Helpman and Kircher

April 2014 16 / 26

Limiting Case: C-D

Production functions:

ψ i

( q

H

, q

L

) = q

β i

H q α i

L for i = 1 , 2;

α i

,

β i

> 0 implies no unique matching within sectors

Grossman, Helpman and Kircher

April 2014 17 / 26

Sorting is unique: according to

α i

/

γ i

Sectoral wage and salary functions: and

β i

/ ( 1

γ i

) w ( q

L

) = w i q

α i

/ γ i

L for q

L

2 Q int

Li r ( q

H

) = r i q

β

H i

/ ( 1

γ i

) for q

H

2 Q int

Hi where w i and r i are wage and salary anchors in sector i

Rise in price of good 2, say due to trade, does not a¤ect wage nor salary inequality within sectors; Ricardo-Viner plus Heckscher-Ohlin e¤ects only

Limiting Case: C-D

Production functions:

ψ i

( q

H

, q

L

) = q

β i

H q α i

L for i = 1 , 2;

α i

,

β i

> 0 implies no unique matching within sectors

Sorting is unique: according to

α i

/

γ i and

β i

/ ( 1

γ i

)

Grossman, Helpman and Kircher

April 2014 17 / 26

Sectoral wage and salary functions: w ( q

L

) = w i q

α i

/ γ i

L for q

L

2 Q int

Li r ( q

H

) = r i q

β

H i

/ ( 1

γ i

) for q

H

2 Q int

Hi where w i and r i are wage and salary anchors in sector i

Rise in price of good 2, say due to trade, does not a¤ect wage nor salary inequality within sectors; Ricardo-Viner plus Heckscher-Ohlin e¤ects only

Limiting Case: C-D

Production functions:

ψ i

( q

H

, q

L

) = q

β i

H q α i

L for i = 1 , 2;

α i

,

β i

> 0 implies no unique matching within sectors

Sorting is unique: according to

α i

/

γ i

Sectoral wage and salary functions: and

β i

/ ( 1

γ i

) w ( q

L

) = w i q

α i

/ γ i

L for q

L

2 Q int

Li r ( q

H

) = r i q

β i

H

/ ( 1

γ i

) for q

H

2 Q int

Hi where w i and r i are wage and salary anchors in sector i

Grossman, Helpman and Kircher

April 2014 17 / 26

Rise in price of good 2, say due to trade, does not a¤ect wage nor salary inequality within sectors; Ricardo-Viner plus Heckscher-Ohlin e¤ects only

Limiting Case: C-D

Production functions:

ψ i

( q

H

, q

L

) = q

β i

H q α i

L for i = 1 , 2;

α i

,

β i

> 0 implies no unique matching within sectors

Sorting is unique: according to

α i

/

γ i

Sectoral wage and salary functions: and

β i

/ ( 1

γ i

) w ( q

L

) = w i q

α i

/ γ i

L for q

L

2 Q int

Li r ( q

H

) = r i q

β i

H

/ ( 1

γ i

) for q

H

2 Q int

Hi where w i and r i are wage and salary anchors in sector i

Rise in price of good 2, say due to trade, does not a¤ect wage nor salary inequality within sectors; Ricardo-Viner plus Heckscher-Ohlin e¤ects only

Grossman, Helpman and Kircher

April 2014 17 / 26

Distribution of Earnings: HL/LH Equilibrium

Proposition Suppose that the sorting conditions are satis…ed for an HL/LH equilibrium in which the best workers sort into sector 1. Then an increase in the price of good 2:

Grossman, Helpman and Kircher

April 2014 18 / 26

1

2

3

4

5 raises the labor cuto¤ q

L and reduces the manager cuto¤ workers and more mangers are employed in sector 2; q

H so that more worsens the matching of all workers except those who switch from sector 1 to sector 2; improves the matching of all managers except those who switch from sector 1 to sector 2; reduces inequality of wages everywhere; and increases inequality of salaries everywhere.

An increase in the price of good 1 has opposite e¤ects

Distribution of Earnings: HL/LH Equilibrium

Proposition Suppose that the sorting conditions are satis…ed for an HL/LH equilibrium in which the best workers sort into sector 1. Then an increase in the price of good 2:

1 raises the labor cuto¤ q

L and reduces the manager cuto¤ workers and more mangers are employed in sector 2; q

H so that more

Grossman, Helpman and Kircher

April 2014 18 / 26

2

3

4

5 worsens the matching of all workers except those who switch from sector 1 to sector 2; improves the matching of all managers except those who switch from sector 1 to sector 2; reduces inequality of wages everywhere; and increases inequality of salaries everywhere.

An increase in the price of good 1 has opposite e¤ects

Distribution of Earnings: HL/LH Equilibrium

Proposition Suppose that the sorting conditions are satis…ed for an HL/LH equilibrium in which the best workers sort into sector 1. Then an increase in the price of good 2:

1

2 raises the labor cuto¤ q

L and reduces the manager cuto¤ workers and more mangers are employed in sector 2; q

H so that more worsens the matching of all workers except those who switch from sector 1 to sector 2;

Grossman, Helpman and Kircher

April 2014 18 / 26

3

4

5 improves the matching of all managers except those who switch from sector 1 to sector 2; reduces inequality of wages everywhere; and increases inequality of salaries everywhere.

An increase in the price of good 1 has opposite e¤ects

Distribution of Earnings: HL/LH Equilibrium

Proposition Suppose that the sorting conditions are satis…ed for an HL/LH equilibrium in which the best workers sort into sector 1. Then an increase in the price of good 2:

1

2

3 raises the labor cuto¤ q

L and reduces the manager cuto¤ workers and more mangers are employed in sector 2; q

H so that more worsens the matching of all workers except those who switch from sector 1 to sector 2; improves the matching of all managers except those who switch from sector 1 to sector 2;

April 2014 18 / 26 Grossman, Helpman and Kircher

4

5 reduces inequality of wages everywhere; and increases inequality of salaries everywhere.

An increase in the price of good 1 has opposite e¤ects

Distribution of Earnings: HL/LH Equilibrium

Proposition Suppose that the sorting conditions are satis…ed for an HL/LH equilibrium in which the best workers sort into sector 1. Then an increase in the price of good 2:

1

2

3

4 raises the labor cuto¤ q

L and reduces the manager cuto¤ workers and more mangers are employed in sector 2; q

H so that more worsens the matching of all workers except those who switch from sector 1 to sector 2; improves the matching of all managers except those who switch from sector 1 to sector 2; reduces inequality of wages everywhere; and

April 2014 18 / 26 Grossman, Helpman and Kircher

5 increases inequality of salaries everywhere.

An increase in the price of good 1 has opposite e¤ects

Distribution of Earnings: HL/LH Equilibrium

Proposition Suppose that the sorting conditions are satis…ed for an HL/LH equilibrium in which the best workers sort into sector 1. Then an increase in the price of good 2:

1

2

3

4

5 raises the labor cuto¤ q

L and reduces the manager cuto¤ workers and more mangers are employed in sector 2; q

H so that more worsens the matching of all workers except those who switch from sector 1 to sector 2; improves the matching of all managers except those who switch from sector 1 to sector 2; reduces inequality of wages everywhere; and increases inequality of salaries everywhere.

Grossman, Helpman and Kircher

April 2014 18 / 26

An increase in the price of good 1 has opposite e¤ects

Distribution of Earnings: HL/LH Equilibrium

Proposition Suppose that the sorting conditions are satis…ed for an HL/LH equilibrium in which the best workers sort into sector 1. Then an increase in the price of good 2:

1

2

3

4

5 raises the labor cuto¤ q

L and reduces the manager cuto¤ workers and more mangers are employed in sector 2; q

H so that more worsens the matching of all workers except those who switch from sector 1 to sector 2; improves the matching of all managers except those who switch from sector 1 to sector 2; reduces inequality of wages everywhere; and increases inequality of salaries everywhere.

An increase in the price of good 1 has opposite e¤ects

Grossman, Helpman and Kircher

April 2014 18 / 26

Sorting and Matching Response in HL/LH Equilibrium

Increase p

2

) raises cut-o¤ q

L and reduces cut-o¤ and managers employed in sector q

H

, so that more workers q

H q

H max d d' sector 2 q * q

H

*

H q

H min c c' q

L min sector 1 a q

L

* a' q

*

L b b' q

L max q

L

Grossman, Helpman and Kircher

April 2014 19 / 26

Worsens matching for all workers and improves matching for all managers except those that switch sectors.

Sorting and Matching Response in HL/LH Equilibrium

Increase p

2

) raises cut-o¤ q

L and reduces cut-o¤ and managers employed in sector q

H

, so that more workers q

H q

H max d d' sector 2 q * q

H

*

H q

H min c c' q

L min sector 1 a q

L

* a' q

*

L b b' q

L max q

L

Grossman, Helpman and Kircher

April 2014 19 / 26

Worsens matching for all workers and improves matching for all managers except those that switch sectors.

Sorting and Matching Response in HL/LH Equilibrium

Increase p

2

) raises cut-o¤ q

L and reduces cut-o¤ and managers employed in sector q

H

, so that more workers q

H q

H max d d' sector 2 q * q

H

*

H q

H min c c' q

L min sector 1 a q

L

* a' q

*

L b b' q

L max q

L

Worsens matching for all workers and improves matching for all managers except those that switch sectors.

Grossman, Helpman and Kircher

April 2014 19 / 26

Compensation Response in HL/LH Equilibrium

5% rise in p_2

Grossman, Helpman and Kircher

April 2014 20 / 26

Evidence: Brazil 1986-1994

Grossman, Helpman and Kircher

April 2014 21 / 26

Sorting and Matching Response in HH/LL Equilibrium q

L and q

H rise q

H max q

H c q

*

H q

H min a q

L min sector 2

Grossman, Helpman and Kircher b

1 b

3 b

2 b q *

L sector 1 q

L max q

L

April 2014 22 / 26

Worker matching can improve and deteriorate in sector 2 ( b

3

)

( b

1

) , deteriorate ( b

2

) , or improve in sector 1

Sorting and Matching Response in HH/LL Equilibrium q

L and q

H rise

Worker matching can improve and deteriorate in sector 2 ( b

3

)

( b

1

) , deteriorate ( b

2

) , or improve in sector 1 q

H max q

H c q

*

H q

H min a q

L min sector 2

Grossman, Helpman and Kircher b

1 b

3 b

2 b q *

L sector 1 q

L max q

L

April 2014 22 / 26

Sorting and Matching Response in HH/LL Equilibrium

Proposition Suppose that the sorting conditions are satis…ed for an HH/LL equilibrium in which the best workers and managers sort into sector 1. Then an increase in the price of good 2:

Grossman, Helpman and Kircher

April 2014 23 / 26

1

2 raises the labor cuto¤ q

L and the manager cuto¤ more mangers are employed in sector 2; q

H has one of the following e¤ects on matching: so that more workers and

1

2

3

4 improves matching for all workers and deteriorates for all managers; deteriorates matching for all workers and improves for all managers; improves matching for low ability inputs of the factor in which sector 2 is intensive and deteriorates for higher ability inputs of this factor, and the opposite for the other input; only (a) or (b) are possible when factor intensities are the same in both sectors, i.e., when

γ

1

=

γ

2

.

Sorting and Matching Response in HH/LL Equilibrium

Proposition Suppose that the sorting conditions are satis…ed for an HH/LL equilibrium in which the best workers and managers sort into sector 1. Then an increase in the price of good 2:

1 raises the labor cuto¤ q

L and the manager cuto¤ more mangers are employed in sector 2; q

H so that more workers and

Grossman, Helpman and Kircher

April 2014 23 / 26

2 has one of the following e¤ects on matching:

1

2

3

4 improves matching for all workers and deteriorates for all managers; deteriorates matching for all workers and improves for all managers; improves matching for low ability inputs of the factor in which sector 2 is intensive and deteriorates for higher ability inputs of this factor, and the opposite for the other input; only (a) or (b) are possible when factor intensities are the same in both sectors, i.e., when

γ

1

=

γ

2

.

Sorting and Matching Response in HH/LL Equilibrium

Proposition Suppose that the sorting conditions are satis…ed for an HH/LL equilibrium in which the best workers and managers sort into sector 1. Then an increase in the price of good 2:

1

2 raises the labor cuto¤ q

L and the manager cuto¤ more mangers are employed in sector 2; q

H has one of the following e¤ects on matching: so that more workers and

Grossman, Helpman and Kircher

April 2014 23 / 26

1

2

3

4 improves matching for all workers and deteriorates for all managers; deteriorates matching for all workers and improves for all managers; improves matching for low ability inputs of the factor in which sector 2 is intensive and deteriorates for higher ability inputs of this factor, and the opposite for the other input; only (a) or (b) are possible when factor intensities are the same in both sectors, i.e., when

γ

1

=

γ

2

.

Sorting and Matching Response in HH/LL Equilibrium

Proposition Suppose that the sorting conditions are satis…ed for an HH/LL equilibrium in which the best workers and managers sort into sector 1. Then an increase in the price of good 2:

1

2 raises the labor cuto¤ q

L and the manager cuto¤ more mangers are employed in sector 2; q

H has one of the following e¤ects on matching: so that more workers and

1 improves matching for all workers and deteriorates for all managers;

Grossman, Helpman and Kircher

April 2014 23 / 26

2

3

4 deteriorates matching for all workers and improves for all managers; improves matching for low ability inputs of the factor in which sector 2 is intensive and deteriorates for higher ability inputs of this factor, and the opposite for the other input; only (a) or (b) are possible when factor intensities are the same in both sectors, i.e., when

γ

1

=

γ

2

.

Sorting and Matching Response in HH/LL Equilibrium

Proposition Suppose that the sorting conditions are satis…ed for an HH/LL equilibrium in which the best workers and managers sort into sector 1. Then an increase in the price of good 2:

1

2 raises the labor cuto¤ q

L and the manager cuto¤ more mangers are employed in sector 2; q

H has one of the following e¤ects on matching: so that more workers and

1

2 improves matching for all workers and deteriorates for all managers; deteriorates matching for all workers and improves for all managers;

Grossman, Helpman and Kircher

April 2014 23 / 26

3

4 improves matching for low ability inputs of the factor in which sector 2 is intensive and deteriorates for higher ability inputs of this factor, and the opposite for the other input; only (a) or (b) are possible when factor intensities are the same in both sectors, i.e., when

γ

1

=

γ

2

.

Sorting and Matching Response in HH/LL Equilibrium

Proposition Suppose that the sorting conditions are satis…ed for an HH/LL equilibrium in which the best workers and managers sort into sector 1. Then an increase in the price of good 2:

1

2 raises the labor cuto¤ q

L and the manager cuto¤ more mangers are employed in sector 2; q

H has one of the following e¤ects on matching: so that more workers and

1

2

3 improves matching for all workers and deteriorates for all managers; deteriorates matching for all workers and improves for all managers; improves matching for low ability inputs of the factor in which sector 2 is intensive and deteriorates for higher ability inputs of this factor, and the opposite for the other input;

Grossman, Helpman and Kircher

April 2014 23 / 26

4 only (a) or (b) are possible when factor intensities are the same in both sectors, i.e., when

γ

1

=

γ

2

.

Sorting and Matching Response in HH/LL Equilibrium

Proposition Suppose that the sorting conditions are satis…ed for an HH/LL equilibrium in which the best workers and managers sort into sector 1. Then an increase in the price of good 2:

1

2 raises the labor cuto¤ q

L and the manager cuto¤ more mangers are employed in sector 2; q

H has one of the following e¤ects on matching: so that more workers and

1

2

3

4 improves matching for all workers and deteriorates for all managers; deteriorates matching for all workers and improves for all managers; improves matching for low ability inputs of the factor in which sector 2 is intensive and deteriorates for higher ability inputs of this factor, and the opposite for the other input; only (a) or (b) are possible when factor intensities are the same in both sectors, i.e., when

γ

1

=

γ

2

.

Grossman, Helpman and Kircher

April 2014 23 / 26

Earnings Response in HH/LL Equilibrium

Proposition Suppose that the sorting conditions are satis…ed for an HH/LL equilibrium in which the best workers and managers sort into sector 1. Then an increase in the price of good 2 has one of the following e¤ects on inequality:

Grossman, Helpman and Kircher

April 2014 24 / 26

1

2 if matching improves for all abilities of factor F

I abilities of factor F

D then inequality rises for F

I and deteriorates for all in every industry and declines between industries with the opposite for F

D if for factor F

I , 2

, F

I

, F

D

2 f H , L g ; matching improves in sector 2 and deteriorate in sector 1 then inequality rises among its low ability inputs and declines among its high ability inputs, while for factor F

D , 2

, whose matching deteriorates in sector 2, the opposite holds for F

I , 2

, F

D , 2

2 f H , L g .

Earnings Response in HH/LL Equilibrium

Proposition Suppose that the sorting conditions are satis…ed for an HH/LL equilibrium in which the best workers and managers sort into sector 1. Then an increase in the price of good 2 has one of the following e¤ects on inequality:

1 if matching improves for all abilities of factor F

I abilities of factor F

D then inequality rises for F

I between industries with the opposite for F

D

, F

I and deteriorates for all in every industry and declines

, F

D

2 f H , L g ;

Grossman, Helpman and Kircher

April 2014 24 / 26

2 if for factor F

I , 2 matching improves in sector 2 and deteriorate in sector 1 then inequality rises among its low ability inputs and declines among its high ability inputs, while for factor F

D , 2

, whose matching deteriorates in sector 2, the opposite holds for F

I , 2

, F

D , 2

2 f H , L g .

Earnings Response in HH/LL Equilibrium

Proposition Suppose that the sorting conditions are satis…ed for an HH/LL equilibrium in which the best workers and managers sort into sector 1. Then an increase in the price of good 2 has one of the following e¤ects on inequality:

1

2 if matching improves for all abilities of factor F

I abilities of factor F

D then inequality rises for F

I and deteriorates for all in every industry and declines between industries with the opposite for F

D if for factor F

I , 2

, F

I

, F

D

2 f H , L g ; matching improves in sector 2 and deteriorate in sector 1 then inequality rises among its low ability inputs and declines among its high ability inputs, while for factor F

D , 2

, whose matching deteriorates in sector 2, the opposite holds for F

I , 2

, F

D , 2

2 f H , L g .

Grossman, Helpman and Kircher

April 2014 24 / 26

Compensation Response in HH/LL Equilibrium

20% rise in p_2

Figure: Cuto¤ shifts to b

1 in previous …gure: Matching improves for all workers and worsens for all managers

Grossman, Helpman and Kircher

April 2014 25 / 26

Conclusions

Can incorporate factor heterogeneity into familiar trade models

Factor comparative advantage generates speci…cities

Distributions of factors a¤ect pattern of trade

Grossman, Helpman and Kircher

April 2014 26 / 26

If productivity of a unit is strictly log supermodular

Positive assortative matching within sectors

Sorting and matching are interdependent

Trade a¤ects within-industry income distribution and across

Future research: Growth and inequality, e¢ ciency and “mismatch”

Conclusions

Can incorporate factor heterogeneity into familiar trade models

Factor comparative advantage generates speci…cities

Distributions of factors a¤ect pattern of trade

If productivity of a unit is strictly log supermodular

Positive assortative matching within sectors

Sorting and matching are interdependent

Trade a¤ects within-industry income distribution and across

Grossman, Helpman and Kircher

April 2014 26 / 26

Future research: Growth and inequality, e¢ ciency and “mismatch”

Conclusions

Can incorporate factor heterogeneity into familiar trade models

Factor comparative advantage generates speci…cities

Distributions of factors a¤ect pattern of trade

If productivity of a unit is strictly log supermodular

Positive assortative matching within sectors

Sorting and matching are interdependent

Trade a¤ects within-industry income distribution and across

Future research: Growth and inequality, e¢ ciency and “mismatch”

Grossman, Helpman and Kircher

April 2014 26 / 26