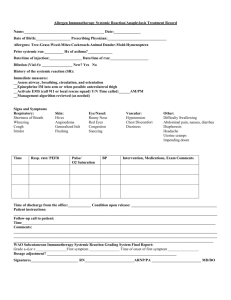

C R S

advertisement