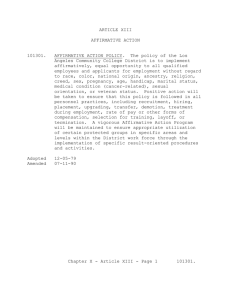

E , S M

advertisement