Meeting the Challenge of Diversity 1968 –1976 The Intensive Educational Development Program and

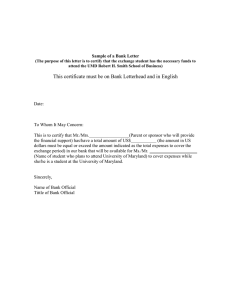

advertisement