Document 14277329

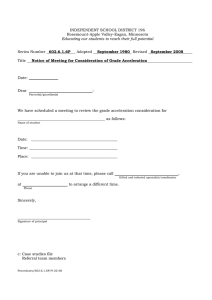

advertisement