Strategic Planning in Higher Education – Best Practices and Benchmarking

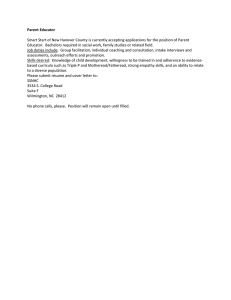

advertisement