Document 14277137

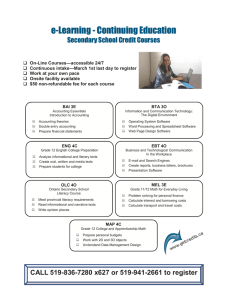

advertisement