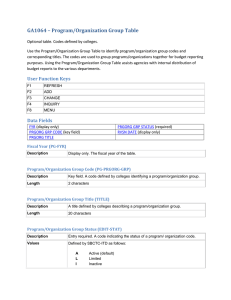

FISCAL RESPONSIBILITIES a resource for governing boards Introduction to

advertisement