Abraham's Legacy: Interfaith Perspectives & Challenges

advertisement

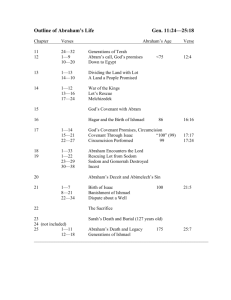

Monday, Sep. 30, 2002 The Legacy of Abraham By DAVID VAN BIEMA;Azadeh Moavevi/Tehran, Nadia Mustafa/New York, Matt Rees and Jamil Hamad/Hebron and Eric Silver/Jerusalem My first real experience of the patriarch Abraham's crossover appeal came on the splendid sun-spangled day in June when I took a cross-town cab to arrange my son's circumcision. Jews have circumcised for thousands of years-ever since God (as the Torah tells it), having made a history-altering pact with Abraham, directed him to "cut my Covenant in your flesh." Some biblical commentators suggest that the circumcision was meant as much as a reminder to the Lord as to the Israelites, a kind of divine Post-it not to extirpate these people. My thought as we rolled eastward across Manhattan was, There must be easier ways. We slowed behind traffic on one of the roads through Central Park, and I found myself tapping my foot. The tune on the cab's stereo was Arabic but with a catchy, bubbling horn section. I asked who was playing. A Moroccan group, said the cabbie. He told me its name. Did I want to know what it was singing? Certainly. It was a plea to Israel from the Arab people. The chorus was, "We have the same father. Why do you treat us this way?" Who might the father be? I asked. "Ibrahim," he said. "The song is called Ismail and Isaac," after his sons. We have the same father. Why do you treat us this way? What did that scrap of a song hint at? First of all, it gave witness that a figure beloved by Jews and Christians has a Muslim constituency, suggesting a connection between Islam and the West that might surprise most Americans in this tense season. But second, it acknowledged that despite this apparent bond, there is still turmoil among the sons of Abraham. It wouldn't do to call Abraham a neglected giant of the Bible; almost everyone knows the outline of his story. But until recently he probably has not received the credit he deserves as a religious innovator. As biblical pioneer of the idea that there is only one God, he is on a par with Moses, St. Paul and Muhammad, responsible for what Thomas Cahill, author of the 1998 history The Gifts of the Jews, calls "a complete departure from everything that has gone before in the evolution of culture and sensibility." In other words, Abraham changed the world. Even less well known to most Americans is the breadth of his following. Jews, who consider him their own, are largely unaware of Abraham's presence in Christianity, which accepts his Torah story as part of the Old Testament and honors him in contexts ranging from the Roman Catholic Mass ("Look with favor on these offerings and accept them as once you accepted ... the sacrifice of Abraham") to a Protestant children's song ("Father Abraham had many sons/And I am one of them and so are you ... "). And neither Jews nor Christians know very much about Abraham's role in Islam, which acknowledges the Torah narrative but with significant changes and additions. The Koran portrays Abraham as the first man to make full surrender to Allah. Each of the five repetitions of daily prayer ends with a reference to him. The holy book recounts Abraham's building of the Ka'aba, the black cube that is Mecca's central shrine. Several of the rituals performed in that city by pilgrims making the hajj recall episodes from his history. Those who cannot journey still join in celebrating the Festival of Sacrifice, in which a lamb or goat is offered up to commemorate the same near sacrifice of a son that the Jews feature at their New Year. It is the holiest single day on the Islamic calendar. In fact, excluding God, Abraham is the only biblical figure who enjoys the unanimous acclaim of all three faiths, the only one (as the song in the cab suggested) referred to by all three as Father. In theory, this remarkable consensus should make him an interfaith superstar, a special resource in these times of anger and mistrust. And since last September, interfaith activists have been scheduling Abraham lectures, Abraham speeches and even "Abraham salons" around the country and overseas. A new book called Abraham: A Journey to the Heart of Three Faiths (William Morrow) by Bruce Feiler, author of the best-selling scriptural travelogue Walking the Bible, espouses their cause. Yet they have an uphill battle. For all the commonality Abraham represents, the answer to the song's plaintive query--Why do you treat us this way?--is written in anathemas and blood over the centuries. If Abraham is indeed father of three faiths, then he is like a father who left a bitterly disputed will. Judaism and Islam, for starters, cannot even agree on which son he almost sacrificed. Then there is Abraham's Covenant with God. Many Jews (and some conservative Christians) believe it granted the Jewish people alone the right to the Holy Land. That belief fuels much of the Israeli settler movement and plays an ever greater role in Israel's hostility toward Palestinian nationalist claims. "Our connection to the land goes back to our first ancestor. Arabs have no right to the land of Israel," says Rabbi Haim Druckman, a settler leader and a parliamentarian with the National Religious Party. This argument infuriates Palestinian Muslims--especially since the Koran claims that Abraham was not a Jew but Islam's first believer. "The people who supported Abraham believed in one God and only one God, and that was the Muslims. Only the Muslims," says Sheik Taysir Tamimi, Yasser Arafat's liaison for religious dialogue. Not exempt from the tripartite rancor, early Christians used their understanding of Abraham, who they claimed found grace outside Jewish law, to prove that the older religion begged for replacement--a contention that helped propel almost two millenniums of anti-Semitism. Abraham is thus a much more difficult--and more interesting--figure than at first he seems. His history constitutes akind of multifaith scandal, a case study for monotheism's darker side, the desire of people to define themselves by excluding or demonizing others. The fate of interfaith stalwarts seeking to undo that heritage and locate in the patriarch a true symbol of accord should be meaningful to all of us suddenly interested in the apparent chasm between Islam and the West. Says Abraham author Feiler: "I believe he's a flawed vessel for reconciliation, but he's the best figure we've got." Feiler began Abraham after the Sept. 11 attacks, seeking a unifying symbol in a time of strife. Instead, the book records his growth from a dewy-eyed Abrahamic novice to a more realistic observer. As he remarks, "When I set out on this journey, I believed ... the Great Abrahamic Hope was an oasis in the deepest deserts of antiquity, and all we had to do was track him down and his descendants would live in perpetual harmony, dancing Kumbaya around the campfire. That oasis, I realized, is just a mirage." The sober understanding Feiler ends up with, however, is a more realistic basis from which to seek reconciliation. ABRAHAM THE JEW Abraham was born, according to tradition, into a family that sold idols--a way of emphasizing the polytheism that reigned in the Middle East before his enlightenment. The stirring first words of the 12th chapter in the Torah's Book of Genesis are God's to him and are often referred to as the Call: "Go forth from your native land/And from your father's house/And I will make of you a great nation/And I will bless those who bless you/And curse him that curses you/And all the families of the earth shall bless themselves by you." Abraham would appear ill suited to the job. To make a nation, one must have an heir, and he is a childless 75-year-old whose wife Sarah is past menopause. Yet he complies, and he and Sarah set off for a desert hinterland--Canaan--and a new spiritual epoch. As they travel, God elaborates on his offer. Abraham's children will be as numerous as grains of dust on the earth and stars in the sky. They will spend 400 years as slaves but ultimately possess the land from the Nile to the Euphrates. The pact is sealed in a mysterious ceremony in a dream, during which the Lord, appearing as a smoking torch, puts himself formally under oath. He requires a different acknowledgment from Abraham: he must inscribe a sign of the Covenant on his body, initiating the Jewish and Muslim customs of circumcision. He is now committed, God notes later, to "keep the way of the Lord to do righteousness and justice." Abraham's life becomes very eventful. He travels to Egypt and back and alights in Canaanite towns that may correspond to present-day Nablus, Hebron and Jerusalem. He grows rich, distinguishing himself sometimes as a warrior king and sometimes as an arch-diplomat. At one point, three strangers appear at his tent. A model of Middle Eastern hospitality, he lays out a feast. They turn out to be divine messengers bearing word that God intends to destroy Sodom, where his nephew Lot lives. Abraham initiates an extraordinary haggling session, persuading the Lord to spare Sodom if 10 righteous people can be found. They can't. Meanwhile, the Torah portrays Abraham's domestic life as a soap opera. Convinced she will have no children, Sarah offers him her young Egyptian slave Hagar to produce an heir. It works. The 86-year-old fathers a boy, Ishmael. Yet God insists that Sarah will conceive, and in a wonder confirming Abraham's faith, she bears his second son, Isaac. Jealous of Hagar's and Ishmael's competing claims on her husband and his legacy, Sarah persuades Abraham to send them out into the desert. God saves the duo and promises Hagar that Ishmael will sire a great nation through 12 sons (assumed by tradition to be 12 Arab tribes). But he stipulates that the Covenant will flow only through Isaac's line. Then, in one last spectacular test of his faith, God directs Abraham to offer up "your son, your only one, whom you love, your Isaac" as a human sacrifice. With an obedience that has troubled modern thinkers from Kierkegaard ("Though Abraham arouses my admiration, he at the same time appalls me") to Bob Dylan ("Abe says, 'Where do you want this killin' done?' God says, 'Out on Highway 61'")--but which seems transcendentally right to traditionalists-the father commences to comply on a mountain called Moriah. Only at the last instant does God stay the father's hand and renew his pledge regarding Abraham's descendants. At age 175, Abraham dies and is laid out next to Sarah, who preceded him, in a plot he has bought in a town later called Hebron. Both sons attend his funeral. That is the story. What is its importance? Despite every effort and argument, there is no way to know what century Abraham lived in, or even whether he actually existed as a person. (If he did live, it would have been between 2100 B.C. and 1500 B.C., hundreds of years before the date most historians assign to the actual birth of the religion called Judaism.) But Abraham represents a revolution in thought. While he is not a pure monotheist (he never suggests that other gods do not exist), he is the Ur-monotheist, the first man in the Bible to abandon all he knows in order to choose the Lord and consciously move ever deeper into that choice, until the point of no return on Moriah. The implications of his breakthrough are almost infinite. To have "one God that counts" instead of a constellation of gods who require occasional ritual appeasement, as Cahill notes in The Gifts of the Jews, means that Abraham's relationship to God "became the matrix of his life," as it would be for millions who followed. A universal God made it easier to imagine a universal code of ethics. Positing a deity intimately involved in the fate of one's children overturned the prevalent image of time as an ever cycling wheel, effectively inventing the idea of a future. Says Eugene Fisher, director of Catholic-Jewish relations for the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops: "Whether you call it submission in Muslim terms, conversion in Christian terms or t'shuva [turning toward God] for the Jews, monotheism is a radically new understanding, the underlying concept of Western civilization." So linked is Abraham's name with this new path that each of the subsequent two monotheistic religions reached back hungrily to enfold him--and belittle the others' claims on him. ABRAHAM THE CHRISTIAN The Church of the Holy Sepulcher in Jerusalem is arguably the most Christian place on earth, and the gray rock mass of Golgotha (or Calgary) inside, the most Christian place in the church. Traditions dating back to the 300s A.D. record that Jesus was crucified here. Just above the rock's Plexiglas-protected expanse is a chapel shared by the Greek Orthodox and Roman Catholic churches. The Catholic side boasts three mosaics. In the center is Mary Magdalene; to the left is Christ, removed from the Cross; and to the right is none other than ... Abraham, about to slay Isaac. Notes Feiler: "The image of Jesus sprawled on the unction stone is nearly identical to the image of Isaac on the altar." The New Testament book Romans proposes Isaac's binding and release as a prophetic foreshadowing of the Resurrection. The man credited with that insight is the Apostle Paul. Jesus mentions Abraham in the Gospels, but it was Paul who did the fine mortise work, citing the patriarch in his New Testament epistles more than any other figure except Christ. Perhaps the most strongly self-identifying Jew among the Apostles, Paul clearly felt an urgency to connect his new movement with the Jewish paterfamilias. He did so primarily through Abraham's original response to God's Call and through the old man's embattled faith, or "hope against hope," as Paul famously put it, that God would bring him a son. Such faith, Paul wrote, made Abraham "the father of all who believe." Yet Paul's Abrahamic bouquet to his birth religion contained poisoned thorns. One of his themes was that a believer no longer needed to be Jewish or to follow Jewish law to be redeemed--the way now lay through Christ. Abraham's story served these arguments well. His Covenant long predated the Jewish law as brought down from the mountain by Moses, and so, wrote Paul, "the promise to Abraham and his descendants ... did not come through law." Nor, Paul argued, did it come through tribal inheritance. The God of the Hebrew Bible deemed Abraham to be "righteous" years before his circumcision, he wrote, which meant that his listeners didn't need to become circumcised Jews to be Abraham's inheritors. Baptism in faith would more than suffice. Paul waffled as to whether Christianity rendered Judaism's Abrahamic Covenant null and void. But his successors assumed so. The 2nd century church father Justin Martyr wrote that far from an indication of grace, circumcision marked Jews "so that your land might become desolate, and your cities burned," something of a self-fulfilling prophecy. Bereft of a divine warrant for their well-being, Jews were at the mercy of their neighbors' worst instincts. In a remarkably frank assessment, the Greek Orthodox bishop of Jerusalem tells Feiler, "What the church did with Abraham was bitter and cruel." ABRAHAM THE MUSLIM No faith is as self-consciously monotheistic as Islam, and its embrace of Abraham is correspondingly joyful. If many Jews know him best as a dynastic grandfather whose grandson Jacob actually founds the nation of Israel, Muslims regard him as one of the four most important prophets. So pure is his submission to the One God that Muhammad later says his own message is but a restoration of Abrahamic faith. The Koran includes scenes from Abraham's childhood in which he chides his father for believing in idols and survives, Daniel-like, in a fiery furnace to which he is condemned for his fealty to Allah. And in the Koranic version of Abraham's ultimate test, Abraham tells his son of God's command, and the boy replies, "O my father! Do that which thou art commanded. Allah willing, thou shalt find me of the steadfast." Notes the Koran approvingly: "They had both surrendered," using the verb whose noun form is the word Islam. For passing such trials, Allah tells Abraham, "Lo, I have appointed thee a leader for mankind!" But not as a Jew. Somewhat like Paul, Islam concluded that God chooses his people on grounds of commitment rather than lineage, meaning that Abraham's only true followers are true believers--i.e., Muslims. Moreover, if Allah ever had a pact with the Jews as a race, they backslid out of it in episodes such as the worship of the golden calf in the Torah's book of Exodus. Indeed, the Koran advises Muslims proselytized by either Jews or Christians to answer, "Nay... (we follow) the religion of Abraham." Then there is the matter of Isaac and Ishmael. Unlike the Torah, the Koran does not specify which son God tells Abraham to sacrifice. Muslim interpreters a generation after Muhammad concluded that the prophet was descended from the slave woman Hagar's boy, Ishmael. Later scholarly opinion determined that Ishmael was also the son who went under the knife. The decision effectively completed the Jewish disenfranchisement. Not only was their genealogical claim void, but their forefather lost his role in the great drama of surrender. THE CONTESTED PATRIMONY Things devolved from there. Jews, stung, took steps to cement Abraham's Jewish identity. The Talmud describes him anachronistically as following Mosaic law and speaking Hebrew. And they severely downgraded Ishmael. Initially, says Shaul Magid, professor of Midrash at New York City's Jewish Theological Seminary, Jewish parents named their boys after Abraham's Arab son, but the custom evaporated as they began living under Muslim rule. By the 11th century the great biblical scholar Rashi, citing earlier authorities, described Ishmael as a "thief" whom "everybody hates," an insult that can still be found in his prominently placed commentary in many Torah editions today and that is taught in many Orthodox religious schools. IbnKathir, a 13th century Koranic commentator, struck back by claiming the Jews had "dishonestly and slanderously" introduced Isaac into the Torah story: "They forced this understanding because Isaac is their father, while Ishmael is the father of the Arabs." That sentiment too survives today on the Muslim side. It is enough to make a grown man cry, which Feiler nearly does. "They took a biblical figure open to all," he writes, "tossed out what they wanted to ignore, ginned up what they wanted to stress and ended up with a symbol of their own uniqueness that looked far more like a mirror image of their fantasies than a reflection of the original story." To his horror, he realized that Abraham "is as much a model for fanaticism as he is for moderation." The Tomb of the Patriarchs, a massive stone structure built by King Herod 2,000 years ago, is the grim living metaphor for dueling Abrahamisms. Despite God's promise that this land would be his people's one day, Abraham in Genesis makes a point of paying Ephron the Hittite 400 silver shekels for a cave in Hebron to serve as a burial plot. He and Sarah were laid there, and later, Scripture adds, so were Isaac and his wife Rebecca, his grandson Jacob and his first wife Leah. Herod erected a grandiose monument at what he thought was the site. For most of the past few hundred years, its Muslim owners, who called it the Mosque of Abraham, allowed Jews to pray near the entrance. When the Israelis took control in 1967, believers of both faiths worshipped side by side. Then in 1994 a radical Israeli settler, Dr. Baruch Goldstein, mowed down 29 Muslims at prayer in the tomb. Custody shifted to a complex scheme granting each side access to parts or all of the tomb on different days but avoiding their meeting. Since the latest intifadeh, the arrangement continues, but the site, hedged about with checkpoints and razor wire in a neighborhood under strict military curfew, presents a message of piety inextricable from violence and mistrust. There is an eerie effortlessness to the way in which fights picked by scriptural revisionists hundreds of years ago feed today's psychology of mutual victimhood. The Jewish Theological Seminary's Magid describes a 1st century tradition in which Ishmael is a bully and Isaac "becomes the persecuted younger brother." That belief has persisted. "The Muslims are very aggressive, like Ishmael," an Israeli settler tells Feiler. "And the Jews are very passive, like Isaac, who nearly allows himself to be killed without talking back. That's why they are killing us, because we don't fight back." Arafat's religious liaison Sheik Tamimi snaps that any Jewish claims based in Genesis are "pure lies, aimed at achieving political gains, at imposing the sovereignty of Israeli occupation on the holy places." HOPES FOR RECONCILIATION It is a staple premise of the interfaith movement, which has been picking at the problem since the late 1800s, that if Muslims, Christians and Jews are ever to respect and understand one another, a key road leads through Abraham. Says Fisher of the Conference of Catholic Bishops: "We can't not talk to each other about him." But identifying a path does not make it passable. Part of the problem, says Jon Levenson, a Harvard Jewish-studies professor who has examined affinities and conflicts in the Abrahamic traditions, is that even before they went to work on him, his story featured a theme of exclusivity. "If you want a symbol for universal humanity, go to Adam," he says. "Don't go to Abraham, because his whole story is about the singling out of one guy to found a new family, a distinct family marked off from the rest of humanity. He was always a particularist." Another stumbling block between Jews and Muslims is that they are working from two different texts. Nonetheless, moderate Islamic leaders have periodically enlisted Abraham as a bridge builder. In 1977 Egypt's President Anwar Sadat, announcing before the Israeli Knesset the brave initiative that would become the 1979 Camp David peace accords, invoked, "Abraham--peace be upon him--greatgrandfather of the Arabs and the Jews." Sadat noted that Abraham had undertaken his great sacrifice "not out of weakness but through free will, prompted by an unshakable belief in the ideals that lend life a profound significance," clearly hoping that both sides would approach Arab-Israeli cohabitation in the same spirit. The accords went through, although this time a sacrifice was completed. Sadat was assassinated in 1981. More recently, seeking a way to reach out to the U.S. that would pass the scrutiny of his nation's dogmatic clerics, moderate Iranian President Muhammad Khatami proposed a "dialogue of civilizations," with Abraham as common ground, in 1998. (The U.N.'s Kofi Annan subsequently adopted the gesture.) Observers assumed Khatami was crafting a smoke screen for political talks. But the former professor of Eastern and Western philosophy seems to regard Abraham as a mascot for his comparatively humanistic, openminded brand of Islam. A more thoroughgoing theological initiative has been undertaken by the Catholic Church. Christianity's position on Abraham had remained depressingly consistent since Justin Martyr's condemnation of the circumcised, but theologians at the Second Vatican Council of 1962-65, shaken by the Holocaust, reread Paul's letters. They noted that at one point Paul calls the Covenant between God and the Jews irrevocable and that in one passage he compares Christians to a wild olive branch grafted onto the tree of Judaism. "If the Covenant between God and the children of Abraham dies," says Fisher, "the branch withers with the roots. Christians would be orphans." The resulting Vatican II document rolled back centuries of anti-Judaism and began a rehabilitation of the notion of Abraham as a Jew. No one has pursued its spirit more avidly than Pope John Paul II, who in March 2000 pressed a prayer card between blocks of Jerusalem's Western Wall: "God of our fathers, you chose Abraham and his descendants to bring your name to the nations ... we wish to commit ourselves to genuine brotherhood with the people of the Covenant." THE EFFECT OF SEPT. 11 Such rapprochement, especially involving Muslims, has been trickier in the past 12 months. Interfaith advocates say that after the attacks, many plans for Jewish-Muslim conversations fell through. One group that bucked the trend was the Children of Abraham Institute, a Charlottesville, Va., association that organizes intensive three-way scriptural studies modeled on Abraham's hospitality to the strangers at his tent. It has held meetings in Denver and at England's Cambridge University and has sent representatives to lecture in Cape Town, South Africa, and parley with imams in Malaysia. It has the ear of the incoming Archbishop of Canterbury. At one of its gatherings last October, University of Virginia professor of Islamic studies Abdulaziz Sachedina expressed an interfaith ideal when he contended that people of faith can "control" their respective interpretations of Abraham's story "so that it doesn't become a source of demonization of the other." As the anniversary of Sept. 11 passed, several new enterprises inaugurated similar efforts. In Portland, Ore., a group called the Abraham Initiative began a two-year, citywide interfaith program. The venerable, Protestant-founded Chautauqua Institution in upstate New York is starting an open-ended Abraham Program involving lectures and trifaith panels. A participant in several such efforts is Feiler. At the end of Abraham, its author announces that understanding how each faith, and seemingly each generation, concocts its own Abraham has liberated him to create his own, whom he whimsically calls "Abraham No. 241." This Abraham, he says, "is perceptive enough to know that his children will fight, murder [and] fly planes into buildings." But he also knows that "his children still crave God, still dream of a moment when they stand alongside one another and pray for their lost father and for the legacy of peace among nations that was his initial mandate from heaven." It is a historical oddity and a hopeful sign that as the three religions battled over Abraham, they continued (without admitting it) to swap Abraham stories. The borrowings and counter borrowings, as old as the conflicts, make far more pleasant reading. The most heartening may be an Islamic tale cited by Feiler whose roots, scholar Reuven Firestone hypothesized, reach into both Judaism and Christianity. It is set after Abraham's near sacrifice of his son, whichever son it was. The moment of truth is just past; the father's hand is stayed. As the boy lies stunned on the altar, God gazes down with pride and compassion and promises to grant his any prayer. "O Lord, I pray this," the boy says. "When any person in any era meets you at the gates of heaven--so long as they believe in one God--I ask that you allow them to enter paradise." -With reporting by Azadeh Moavevi/Tehran, Nadia Mustafa/New York, Matt Rees and Jamil Hamad/Hebron and Eric Silver/Jerusalem Judaism Islam Christianity.