Reforming Student Aid to Improve College Choices and Completion February 2013

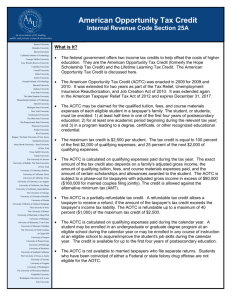

advertisement