The Literary Cycle Next Stop…

advertisement

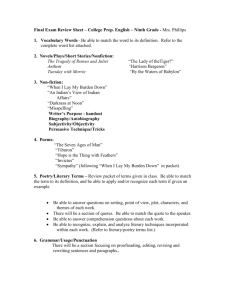

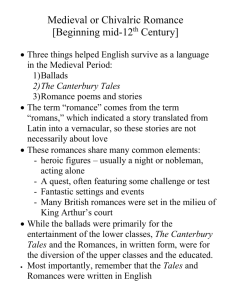

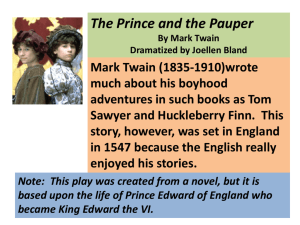

Next Stop… The Literary Cycle Frye and the Lit Cycle: • Frye uses images of nature to explain his theories in both “Motive” and “Singing School • The Literary Cycle repeats patterns in nature, which is likely why Frye chose the island, and nature as his analogy in both his essays. The major conventions of Western Literature as discussed in Frye’s essay are: Comedy • Romance • Tragedy • Satire • In Frye’s essay he expresses his belief that literature is NOT uniquely inspired, despite the romantic theory that expresses otherwise. • Instead, he believes that, “a writer’s desire to write can only have come from previous experience in literature”, “and he’s start by imitating whatever he’s read”. There is a pedigree to writing. • This leads to conventions in FORM as well as CONTENT. • He says again and again that, “literature can derive its form only from itself”. • The major conventions (stated earlier) are the “typical ways in which stories get told”. • In Frye’s view, all literature tells a large cyclical story, “of the loss and regaining of identity”. • It can be the hero’s quest, the lover’s plight… The Literary Cycle Lets Break it Down… Each genre, in its traditional sense, is related to certain aspects of nature Genre Life Stage Sun Season Water Moon Math Comedy Birth Dawn Spring Rain 1/4 +: Add Romance Youth/ Marriage High Noon (Zenith) Summer Fountain Full x: Multiply Tragedy Old Age/ Death Sunset/ Twilight Fall River/ Stream 1/2 or Crescent -: Subtract Satire Death/ Division/ Divorce/ Rebirth Night/ Darkness Winter Sea/ Ocean No Moon/ New Moon : Divide Comedy: • Comedy in the academic sense is a literary work that aims primarily to provoke laughter. • Unlike tragedy, which seeks to engage profound emotions and sympathies, comedy strives to entertain chiefly through criticism and ridicule of man's customs and institutions. • Although it is usually used in reference to the drama, in the Middle Ages comedy was associated with vernacular language and a happy ending. Thus, the term was also applied to non-dramatic works as well. Romance: • As a literary genre of high culture, romance or chivalric romance were fantastic stories about the marvelous adventures of a chivalrous, heroic knight, often of super-human ability, who often goes on a quest. • Romances reworked legends, fairy tales, and history to suit tastes. • The modern image of the medieval is more influenced by the romance than by any other medieval genre, and the standard image of the medieval invokes knights, distressed damsels, dragons, and other romantic tropes. • During the early 13th century romances were increasingly written as prose. • In later romances, there is a tendency to emphasize themes of courtly love, such as faithfulness in adversity. • Later, "romance" moved from the magical and fantastic to somewhat eerie “Gothic” adventure narratives. Tragedy: • Tragedy is a drama of a serious and dignified character that typically describes the development of a conflict between the protagonist and a superior force (such as destiny, circumstance, or society) and reaches a sorrowful or disastrous conclusion. • Tragedy can be distinguished into three periods, each with a characteristic emphasis and style: Attica, in Greece, in the 5th century BC; Elizabethan and Jacobean England (1558 – 1625); and 17th-century France. • The idea of tragedy also found embodiment in other literary forms, especially the novel. Satire: • In satire, vices and shortcomings of certain characters or a community are held up to ridicule, ideally with the intent of shaming individuals, and society itself, into improvement. • Although satire is usually meant to be funny, its greater purpose is constructive social criticism, using wit as a weapon. A common feature of satire is strong irony or sarcasm, but parody, burlesque, exaggeration, juxtaposition, comparison and analogy, are all frequently used in satirical speech and writing.