Document 14261846

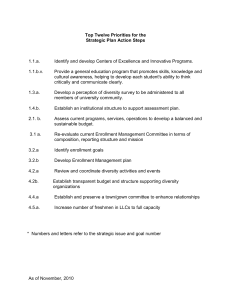

advertisement

2015 JEPPA VOL.5, ISSUE 7 THE RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN SCHOOL SIZE AND HIGH SCHOOL COMPLETION: A WISCONSIN STUDY David G. Buckman, Ph.D. DePaul University Henry Tran, Ph.D. University of South Carolina ABSTRACT The potential benefits of school size on student outcomes have been debated for decades, but research on the matter has been far from conclusive. This study seeks to contribute to school size research by examining the relationship between high schools’ size (enrollment) and their student on-time (i.e., graduates within four years) completion rates in public, non-charter high schools in the state of Wisconsin. This outcome is unique in that it is relatively unexamined and captures not only students who drop out but also those that are retained a grade. Results from our multiple regression analysis (OLS) support the argument that school enrollment is negatively related to high school on-time completion rates (b=-.0000146, p=.007), after controlling for a hosts of student demographic and school environmental factors. We interpret this result through Barker and Gump’s (1964) staffing theory to better understand the chain of the events that may have resulted in our finding. To contribute to scholarly discussions concerning the “optimal school” size for student outcomes, we found that a school with an enrollment size of 156.25 would yield the highest completion rates based on the data within our sample. 2015 JEPPA VOL.5, ISSUE 7 INTRODUCTION The potential influence of school size on student outcomes have been debated for decades. Some findings from past research has favored smaller schools as ideal for student learning as it relates to student academic achievement (Kuziemko, 2004; Lamdin, 1996; Lee and Smith, 1997), however, these results are far from conclusive (Michelson, 1972; Sanders, 1993). This study seeks to contribute to the knowledge base by examining the relationship between the size of high schools and their student completion rates, a relatively unexplored student success metric. Aligning with prior recommendations made by scholars of school size research (Bard, Gardner, & Wieland, 2006), many school districts across the United States have consolidated with one another to decrease per-pupil costs, taking advantage of economy of scale. Economy of scale refers to the cost advantages that organizations obtain because of characteristics such as size, output, or scale of operation, which as a result reduces cost per unit by distributing cost over more units of output (Panzar & Willig, 1977). By reducing the cost per unit, the consolidation of districts provide more resource opportunities for extra-curricular activities, increase student interaction, and offer more diverse curriculum (Smith & DeYoung, 1988) than smaller schools. While it is possible for school districts to merge without effecting high school size, often school districts consolidated to increase equity and efficiency of high schools (Haller, 1992) by increasing student enrollment. As a result of school district and school consolidation, school enrollment is eight times larger than it was one hundred years ago and the numbers of school districts have substantially decreased (Lowen, Haley, & Burnet, 2010). The consolidation of schools and school districts often occur to accommodate a larger student body, decrease the number of faculty, and increase variety of courses. This is because schools or school districts with dwindling enrollment that are incapable of financially sustaining the learning environment often consolidate to increase academic and financial stability through cumulative per-pupil expenditure. It is also important to note that declining enrollments of small schools and its associated decline in per student state funding have caused severe financial problems for many of these schools. Smaller schools with low enrollment may struggle to allocate funds necessary to support not only extracurricular activities, but also for the quality maintenance of the learning environment. Consequently, to maintain curricular quality (e.g., incorporation of technology, surplus of academic programs, and facilities), some school districts consolidate voluntarily to save programs and facilities (Bard, Gardener, & Wieland, 2006). Although school district consolidation may be the answer to some district financial issues, researchers have noted that large schools, as a result of district consolidation, have been associated with limited parental involvement in student learning, increased discipline problems, and elevated teacher/student conflicts (Dale & Allen, 1995). At smaller schools, teachers and school level administrators typically have more job responsibilities. Principals and teachers may find that due to the contextual complexity of small schools their roles may not be as bounded as those of larger schools (Clarke & Wildly, 2004). For example, teachers may be required to perform duties ideally performed by administrators and school administrators may have teaching responsibilities. School size and class size often increase concurrently (Alspaugh, 1994), therefore, to accommodate for increases in school size, teacher’s instructional practices are affected by the increased need to focus more time on classroom management and student discipline. Just as 2015 JEPPA VOL.5, ISSUE 7 teachers must accommodate to the increases in the student population, administrators at larger schools can also be distracted by an increased need to address student discipline at the expense of spending more time focusing on instructional leadership needs when compared to administrators at smaller schools. In fact, larger schools often require more assistant principals, in which one of the administrators may be responsible for discipline, while another for instructional leadership. In addition to the aforementioned issues, school size is also important because of its potential impact on student outcomes, such as high school completion. Student high school completion matters because of its predictive power for increased levels of human capital and success in adulthood for graduates (Lee & Burkam, 2003). Failing to complete high school has been found to be associated with much lower future earnings (Rumberger, 1987), more arrest (Thornberry, Moore, and Christianson, 1985), and increase tax payer costs (Bjerk, 2012). So while school districts throughout the U.S. continue to increase school size by consolidating for the purposes of cost efficiency and other district related benefits, we question what these mergers may mean for students’ high school completions. In the next section, we will review arguments that support the popularity of the espoused advantages of larger schools. We proceed by citing prior evidence that counter these arguments and highlight prior findings of the advantages of small schools. We then follow the review of literature with a potential explanation of how school size impacts high school completion through the theoretical perspective of the Staffing Theory (Barker & Gump, 1964). REVIEW OF LITERATURE Popular Large School Arguments Researchers argue that larger schools can increase savings by reducing redundancy and strengthening purchasing power (Lee & Smith, 1997). Gilbert (1999) discusses the price reduction benefit merchants offer consumers for purchasing items in large quantities. The increased number of students in a school allows for bulk purchases, resulting in lower per-pupil spending due to the reduced cost of supplies (Lee & Smith, 1997). Lee and Smith (1997) also argue that larger schools have more potential to differentiate instruction. For instance, at larger schools, teachers may be afforded more opportunities to individualize a student’s education based on their learning abilities because of the increased likelihood that there will be larger numbers of students with similar abilities. By having more students with similar learning attributes, the teacher can create small learning groups that better provide focused instruction. Other than the aforementioned motives described by Lee and Smith (1997), Tanner and West (2011) buttress the recommendation for larger schools by recognizing that larger schools provide not only quality education for students with emphasis on increased opportunities for academic success, but also provide a well-rounded education with possibilities for other forms of scholastic involvement. Arguments for larger schools could be made to address the need for more competitive sports teams, bands, and maintaining a cohesive relationship between the school and the community (Tanner & West, 2011). If a successful program is defined by “winning” performances, then ultimately, as the pool of candidates for a particular extracurricular activity increases, the potential quality of that particular program increases concurrently due to increased selective competition. Ideally, the more individuals available to choose from in a candidate pool, the pool becomes more competitive and the probability of 2015 JEPPA VOL.5, ISSUE 7 selecting a highly skilled individual increases. Therefore it is not abnormal that “one of the most frequently observed reasons for encouraging the construction of large high schools has been the perceived need to have a winning football team (Tanner & West, p. 18, 2011).” In a study conducted by Coladarci and Cobb (1996), they concluded that student achievement (as defined by composite standardized math and reading scores) was unrelated to school size, despite the fact that smaller schools have higher participation rates in extracurricular activities. This contributes to the evidence that debunks the argument for an indirect effect of school size on student achievement. Moreover, Friedkin and Necochea (1988) found positive effects of increased school size on student achievement, however, only in areas with high Socioeconomic Status (SES). Increased SES of the school can be associated to the increase in school system size, which produces opportunities for improved school system performances (Friedkin & Necochea, 1988). Their research also supports that these larger schools may not thrive in low SES environments due to low operations performance and financial constraints. Small School Rebuttal Large schools are able to allocate more funds than smaller schools within the school supplies area of their budget because of the savings associated with larger purchases, however, Lindahl and Cain (2012) found that the per-pupil expenditures of large schools do not differ from small schools. Conversely, their research found that large schools demand significantly more local effort in the form of taxes than medium or small schools. In agreement with Lindahl and Cain’s (2012) findings, Lee and Smith (1997) identify the costs of increased administrative staff, higher cost in material distribution, and increased cost in student transportation associated with large schools that collectively equipoise any savings. One argument for larger schools is the claim that it facilitates the opportunity to provide more diverse curriculum based on the increased potential for a large numbers of students with similar interests and abilities. In theory, large schools create programs to address a larger number of students’ individual needs, while small schools focus on core courses that may or may not meet their academic needs (Buzacott, 1982). For example, larger schools may offer a more diverse array of elective courses (e.g., forensic science, sculpting, advanced technology courses), while smaller courses may provide more emphasis on the core courses (e.g., math, reading and science). While the curriculum may be narrower at smaller schools, Lee and Smith (1997) find that they produce more positive social relationships among students and higher average achievement than present at larger schools by limiting students to the same curriculum regardless of interests, abilities, and social backgrounds. This can be seen as a positive attribute of small schooling because of the increased learning opportunities that can be provided through equitable distribution of students with different achievement levels within the same classes (Lee & Smith, 1997). Perhaps because of this, smaller schools have been found to be better suited to increase achievement in poor performing, low income student populations (Friedkin & Necochea, 1988). Optimal School Size As it can be determined from the arguments presented for both large schools and small schools, there is no consensus that one is more advantageous than the other. Although larger schools provided opportunities for financial savings through discounts on larger purchases for 2015 JEPPA VOL.5, ISSUE 7 administration (Lee & Smith, 1997; Gilbert, 1999), they also encounter negative attributes in the form of higher dropout rate, increased levels of school violence, and tardiness (Heaviside, Rowand, Williams, & Farris, 1998). Smaller schools have been associated with better social relationships, and increased levels of achievement in rural and impoverished areas (Lee & Smith, 1997; Raywid, 1997), however, smaller schools also lack variety and opportunities for student to participate in many different extracurricular activities (Tanner & West, 2011). Tanner and West (2011) recognized that smaller schools have fewer accounts of school violence than larger schools. In addition, Heaviside et al. (1998) found that schools exceeding 1,000 students sustained more discipline issues pertaining to tardiness, physical conflict, as well as alcohol and drug offenses. Smaller schools have been reported to have higher attendance rates, lower dropout rates, higher grade point averages, and higher levels of participation in extracurricular activities (Viadero, 2001). While larger schools are more capable of financially sustaining a highly functional educational environment rich in academic and extracurricular diversity (Tanner & West, 2011). To reap the benefits associated with both large and small schools, school districts may benefit from building from an ideal size for operations. The term “optimal school size” has been used often within school enrollment literature pertaining to benefits associated with accountability, school consolidation, and district costs (Lowen, Haley, & Burnett, 2010). Despite its common use, researchers have defined the term differently because optimal size is often defined as the size that best links the main predictor to the various outcomes studied within their research. In this study, we examine the issue of optimal size, defined as the number of students enrolled in a school that supports the highest graduation completion rate, controlling for a host of factors including student achievement (based off state standardized test scores) and school environment. Researchers have noted that high schools exceeding 1,000 students are at risk for issues related to academic and disciplinary issues (Heaviside et al., 1998). While optimal high school size has not been quantified often in school size literature, researchers have often referred to the optimal school size of 400 as reported by Howley (1994). Specifically, Howley suggests that a total student enrollment of 400 is the optimal school size capable of supporting student curricular needs. Our work adds to the literature by reporting a data-based suggestion of the optimal school size for high school completion rates. High School Dropout Lee and Burkam (2003) suggest that personal characteristics of individual students are the most common explanation for why students drop out of high school. Explanatory variables found in student dropout research often consist of (a) socioeconomic status, (b) inner city residency, and (c) academic status (Lee & Burkam, 2003). By framing research in this manner, Lee and Burkam (2003) allude that dropping out is identified as the result of a series of unwise choices made by students, which are influenced by their backgrounds and behaviors. Beyond the students’ personal backgrounds and behaviors, the structure of the school can also be a predictor of student of drop out. School enrollment, sector, and urban status have all been recognized as predictors associated with student dropout (Rumberg & Thomas, 2000). Within their research, they found that dropout rates were much higher in large, public, urban schools after controlling for school related demographics (i.e., resources, attendance, student composition). The influence of school size on student dropouts is an area that warrants further discussion. 2015 JEPPA VOL.5, ISSUE 7 School Size and Dropout Findings When reviewing school size research, researchers have provided evidence supporting school size having a veritable effect on high school dropout. While similar, on-time (four years) high school completion, which is the focus of our study, remains distinct because our focal group of four-year cohorts recognizes those who have dropped out of school as well as those enrolled but not completing on time. This expanded focal group has not been an area of emphasis by other scholars, but their research is worth reviewing to provide a foundation for this study. Cotton (1996) reviewed ten studies pertaining to school size and high school dropout rates, finding that in nine of the ten studies, smaller schools produced lower levels of high school dropout. Similarly, Gladden (1998) found higher levels of high school completion in smaller schools compared to larger schools. Further research found by Pittman and Haughwout (1987) report that schools with a graduating class of fewer than 667 students produced an average dropout rate of 6.4%, while schools with a graduating class exceeding 2091 students produced an average dropout rate of 12.1%. In this study, Barker and Gumps’s (1964) Staffing Theory was used as a theoretical framework to help us understand the relationship between high schools’ size and student completion. This theory addresses school human resources issues pertaining to staffing and how the environment or behavior setting based on staffing can impact student success. As such, our study addresses the school environment for a four-year period and uses this theory to explain how school related issues pertaining to school size can influence student outcomes (i.e., high school completion). THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK Staffing Theory Barker and Gump’s (1964) Staffing Theory recognizes the implications of a behavior setting (e.g., school environment) being either overstaffed or understaffed. A behavior setting is defined as an environment in which individuals can be seen as a unique and integral part of an organization, or anonymous and replaceable (Barker & Gump, 1964). Understaffing is recognized as a description of an environment whose organization is not equipped with the adequate labor force to address the behavioral environments goals (e.g., well-rounded education), while overstaffing occurs when there is a profusion of personnel available to promote the behavioral environments goals. In this particular study, we identify an overstaffed environment as a proxy for large schools given that larger schools are more likely to have a “profusion of personnel available” relative to smaller schools, while an understaffed environment serves as a proxy for small schools. However, the impact of each may have confounding effects on its members. Based on Barker & Gump’s (1964) theory, one could hypothesize that students at smaller schools are more likely to display the following behavioral consequences in comparison to larger high schools: 1) Greater effort. Greater individual effort can take the form of “harder” work or longer hours. The greater effort is directed both toward the primary goals of the setting and along the maintenance routes. When the assistant yearbook 2015 JEPPA VOL.5, ISSUE 7 editor leaves, with no one available for replacement, the editor proofreads all the galleys instead of half of them. 2) Working with more difficult and important tasks. There is, in most settings, a hierarchy of tasks with respect to difficulty and importance.The inexperienced sophomore has to take the lead role in the play when the experienced senior becomes ill. [Ultimately, these scenarios provide examples of how at smaller schools, individuals who may not be typically given the prospect to participate in certain experiences are provided opportunities to expand their abilities and gain new skills because of the availability or lack of participants]. (p. 24) When interpreting the examples provided by the researchers, one may conclude that due to the increased amount of work and responsibilities associated with an understaffed work force (i.e., small schools), there is also an elevated amount of social pressure and additional opportunities to become involved in the environmental setting. In smaller schools, individuals are likely to have increased opportunities to participate in leadership roles, in addition, they are likely to have less opportunity to remain anonymous in the crowd. This is true not only for the employees, such as faculty, who have increased opportunities to get to know (and care for) the students of the school on a more personal level, but also for students, who have increased opportunities to be known. This theory purports that as overstaffing in school system become potent (as a result of school size), the amount of individual responsibility decrease concurrently. In this scenario, employees, such as faculty, have less opportunity to get to know (and care for) the students and the students have fewer opportunities to be known. Staffing Theory (Baker & Gump, 1964) and the components associated to an understaffed school environment may be linked to support high school completion rates. The small school environment supports higher levels of pressure to succeed, greater involvement in the school setting, as well as more student responsibility. As such, because of the scarcity of students enrolled in the school, each individual become an essential and integral component of the student population. Also, with such high levels of visibility, foreseen signs of student drop-out and class failure may be more noticeable by school personnel who are already familiar with the students and preventive measures can be taken promptly. Based on the latter statement concerning this theory, we explore the relationship between school size and high school completion. PURPOSE As local and national government implement new school initiatives to expand school consolidations, it is important to recognize issues affecting student outcomes at the micro level. This study intends to offer current research in an area that warrants further investigation. Specifically, this study offers an empirical examination of the relationship between high school size and student success (e.g., on-time high school completion) in public, non-charter high schools in the state of Wisconsin. 2015 JEPPA VOL.5, ISSUE 7 ADVANCEMENTS This study advances the body of research concerning high school dropout (Lee & Burkam, 2003; Rumberg & Thomas, 2000) by first extending the outcome emphasis to high school completion and then accounting for unique variables (i.e., minimal school performance, percentage of drug arrest per county, principal retention, county wages, county educational attainment) that may be related to student completion, as well as commonly used controls frequently incorporated in prior student dropout research (i.e., SES, school performance, perpupil expenditure). The aforementioned studies both addressed predictors of student drop out, however, their research differs by only addressing individual and school level factors with emphasis on socioeconomic status (SES), minority concentration, and school achievement, ignoring school size, community demographics that may influence dropout (i.e., percentage of drug related arrest, community wages, community education level), or leadership stability (e.g., principal turnover) as potential predictors associated with high school completion. Unlike other related studies that focus on student dropout as an outcome, our study concerning student on-time high school completion utilizes the data of a four-year cohort from non-charter, public high schools and accounts for not only dropout, but also individuals who remain in school but not completing on-time. In doing so, we attempt to identify whether school size predicts high school students’ completion rates. Ultimately this study intends to address the following research question: 1) Is there a relationship between high schools’ enrollment (school size) and student completion rates? METHODOLOGY The population of interest for this study is all traditional (non-charter) public high schools in the states of Wisconsin (N=511), of which our sample contains 391. Patterns were examined for missing schools, which revealed that they were either state schools (i.e., correctional schools, school for the deaf/blind, and health services schools), extremely small schools (whereby individual students could be identified) and/or new schools without four years of data. School and district related variables were obtained from the Wisconsin Department of Public Instruction (WDPI), whereas county variables were obtained from the Bureau of Labor Statistics and the University of Wisconsin Population Health Institute. The dependent variable for this study is Wisconsin’s public high school “on-time” completion rates for a four year cohort. “On-time” refers to students who graduated high school within four years. Students who transferred to other schools were completely removed from the cohort. Therefore, those who do not complete are comprised of students who were retained (or held back) so are therefore still in the school or have dropped out. Because of the aggregated nature of the completion rate variable by time, the main predictor and all covariates were also averaged across four years. These variables included school’s enrollment, combination status (i.e., whether a school was a high school or middle/high school combination), percent of students scoring at minimal performance, percent of principals retained (i.e., 100% if the same principal remained at the same school for four years), percent of student suspensions, percent of students on free/reduced lunch, districts’ total per student education costs, county percent of drug arrests, percent of adults whose highest education attainment is less than a high school graduation, and total quarterly wage. Of the sample of 2015 JEPPA VOL.5, ISSUE 7 schools, 370 (94.63%) were non-combination high schools and 21 (5.37%) were combination schools (middle/high school). Further descriptive statistics for the remaining variables are provided in table 1. Table 1 DESCRIPTIVE STATISTICS (n=391) Variable Mean Std. Dev. Min Max Completion Rate (School %) .92 0.78 .29 1 School Enrollment 621.77 512.68 26.5 2260.75 Minimal Performance (School %) .17 .08 .03 .68 Drug Arrest (County %) .004 .002 .0004 .016 Districts’ Total Per Student Costs 2.74e+07 8.09e+07 10,493 5.51e+08 Principal Retention (County %) .87 .15 .5 1 County Total Quarterly Wage 9.35e+08 1.62e+09 5,792,104 6.06e+09 Less than high school (County %) .10 .03 .04 .18 Free/Reduced Lunch (School %) .33 .15 0 .86 Suspension (School %) .05 .05 0 .57 In order to examine the influence of school enrollment on high school completion rates, a regression analysis was employed. The clustering of data by school, county and district naturally suggests that a multilevel model may be appropriate. Consequently, we compared an ordinary least squares model (OLS) to a multilevel model that accounts for groupings. Results from the likelihood-ratio test suggests that accounting for clustering was not necessary, χ2 (df=2) =.0.0, p=1. As a result, our analyses proceeded with an OLS regression model. 2015 JEPPA VOL.5, ISSUE 7 RESULTS To address our primary research question, our findings suggest that school enrollment is negatively associated with high school “on-time” completion rates. Specifically we find that for every 1,000 students that are enrolled in a school, the completion rate drops by about 1.46% (b=.0000146, p=.007). In addition, the county percentage of drug related arrests, districts’ per student total education costs and schools’ percent of minimal performance were all found to be negatively related to “on-time” completion rates. However, of all the variables examined, standardized regression estimates indicate that the factor that has the largest relative association with completion rates is student performance. Specifically, schools with a larger share of lower performing students have lower completion rates. This finding is aligned with prior research (Deming, 2009). The second strongest predictor of high school completion was total education costs. Specifically, the cost of education was found to be negatively related to high school completion. This finding may be due to the fact that certain students who cost more to educate (e.g., students identified as English Language Learners, in Special Education, coming from impoverished backgrounds) also tend to have lower high school completion rates (Verstegen, 2011). The full results of the regression are displayed in table 2. Coefficients are reported with robust standard errors. These results are more conservative as the modified standard errors help address issues concerning the violation of regression assumptions (e.g., normality, heteroskedasticity). 2015 JEPPA VOL.5, ISSUE 7 Table 2 REGRESSION RESULTS FOR PREDICTORS OF HIGH SCHOOL COMPLETION RATES School Enrollment Minimal Performance (School %) Combination Schools Drug Arrest (County %) Total Education Cost Principal Retention (School %) County Total Quarterly Wages Adults without high school degree (County %) Students on Free/Reduced Lunch (School %) Suspensions (School %) Constant r2 n Robust standard errors in parentheses *** p<0.01, ** p<0.05 Completion Rate -1.46e-05*** (5.36e-06) -0.464*** (0.0959) -0.00376 (0.0107) -2.063** (0.979) -3.26e-10** (1.32e-10) -0.0111 (0.0154) 0 (0) 0.0693 (0.0728) -0.0414 (0.0263) 0.0369 (0.151) 1.038*** (0.0185) β -.096 -.490 -.011 -.064 -.336 -.021 .026 .026 -.079 .024 0.65 391 In an effort to contribute to the discussion concerning optimum school size, predicted outcomes were examined relative to each school enrollment size as found between the range of 26.5 to 2260.75 in our sample. According to the results of our study, the optimum school size found within the data set is 156.25 for non-combination (i.e., the majority) Wisconsin public high schools, which yielded a 100% completion rate. A scatterplot comparing high school enrollment to completion rates is displayed in figure 1, a trend line was superimposed onto the figure to highlight the negative relationship found between enrollment and completion rates. 2015 JEPPA VOL.5, ISSUE 7 High School Completion Rates Figure 1 SCATTER PLOT OF SCHOOL ENROLLMENT ON HIGH SCHOOL COMPLETION RATES 0.95 0.85 0.75 0.65 0.55 0.45 0.35 0 500 1000 1500 2000 2500 High School Enrollment CONCLUSION Our study found evidence to support the argument that school enrollment is negatively related to high school “on-time” completion rates. Interpreting this finding through Barker and Gump’s (1964) staffing theory suggests that students of smaller schools may benefit from the increased attention they are likely to receive from education professionals such as teachers and principals, given the difficulty for students to remain invisible at a smaller school relative to a larger school. In addition, the theory suggests that students at smaller schools will likely face increased pressure to be involved in the school community and succeed. While additional research is needed to validate the mechanism (e.g., pressure, increased student responsibility) by which school size is related to high school completion rates, this study does provide evidence to suggest that the two variables are statistically related. In addition to school enrollment, county of drug related arrests, districts’ per student total education costs, and schools’ percent of minimal performance were all found to be negatively related to “on-time” completion rates. According to our standardized regression estimates, of the variables examined, the factor that mattered most for high school completion rates is student performance. Specifically, a school with a larger percentage of low performers is more likely to have lower completion rates. The finding of the association between schools’ percentage of low performers relative to their students’ completion rates may be due to several reasons. For instance, lower performers may have less ability or confidence to meet completion requirements. Students who do not perform well in school may feel that they are mismatched for education or that they are unlikely able to finish. In addition, although student poverty and low education level of county residents are accounted for in our model, there may be other unaccounted for variables (e.g., educational aspiration of peer and family members) that may be related to both high schools with a large number of low performers and their completion rates. Therefore, schools with a larger share of low performing students may be more likely to drop out due to the influence of their peers that also have not completed high school. 2015 JEPPA VOL.5, ISSUE 7 LIMITATIONS While it is preferable to have individual panel level data, such data were not available. Consequently, we were not able to identify the exact number of students who dropped out as compared to those who were retained. Future studies should seek to follow the educational trajectory of individual students, controlling for factors that may impact the “on-time” completion rates of those students. Further depth can also be added to our findings by examining the same factors we explored on a five year completion cohort, which would capture those students who were retained a year. Furthermore, the data based optimum school size of 156.25 that was found in this study must be interpreted with caution. This number is based on averages generated from statistics, and does not account for specific contexts and circumstances for individual schools that may warrant larger or smaller school sizes. School leaders and policymakers must take into consideration many factors, including student population and financial implications when using the modification of school size to improve student outcomes. RECOMMENDATIONS Based on our findings, further exploration concerning the impact of school size on student performance is warranted. As previously noted, school size and student achievement has been inconclusive when determining whether small schools or large schools have a greater impact on student achievement (Coladarci & Cobb, 1996; Friedkin & Necochea, 1988; Lee & Smith, 1997). Issues such as student demographics, student and school wealth (SES), as well as participation in extracurricular activities have all been identified as issues noteworthy of exploration when linking school size to student performance. Because of the strength of the association between low performance and “on-time” school completion rates, arguments and findings for the importance of early childhood intervention and stronger academic preparation for students is supported (Deming, 2009). Past studies have found that students who are underprepared face academic problems (e.g., they are required to take remedial courses) at higher education institutions (Bettinger & Long, 2009). Our findings suggests that the under preparation may be more serious than initially thought as underprepared students may not even make it to college. This is likely true for both dropout students and for those who are retained a grade, because past research has suggested that the latter are more likely to become the former and both are less likely to enroll in post-secondary institutions (Goldenring & Davis, 2003). In sum, high school completion is important for many reasons. For instance, even from a communal economics perspective, high school graduates are more likely to earn higher salaries than non-graduates (Lee & Burkham, 2003) which results in higher taxes being contributed to address societal needs. Graduates are also less likely to be arrested (Thornberry, Moore and Christianson, 1985) which not only reduces taxpayer costs, but promotes a safer environment for our citizens. From the individual perspective, the benefits of high school completion can range from increased self-esteem to better life outcomes in general. The variables that we addressed in this study help uncover more factors that contribute to high school student success. By better understanding these, as well as other influential factors, we will be in a position to better help students cross that high school finish line. 2015 JEPPA VOL.5, ISSUE 7 REFERENCES Alspaugh, J. W. (1994). The relationship between school size, student teacher ratio and school efficiency. Education, 114(4), 593. Bard, J., Gardener, C., & Wieland, R. (n.d.). Rural school consolidation: History, research summary, conclusions, and recommendations. Rural Educator, 27(2), 40-48. Barker, R. G., & Gump, P. V. (1964). Big school, small school. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press. Bjerk, D. (2012). Re-examining the impact of dropping out on criminal labor outcomes in early adulthool. Economics of Education Review, 31, 110-122. Buzacott, J. A. (1982). Scale in production systems. Oxford: Pergamon Press. Clarke, S., & Wildy, H. (2004). Context Counts: Viewing small school leadership from the inside out. Journal of Educational Administration, 42(5), 555-572. Coladarci, T., & Cobb, C. D. (1996). Extracurricular participation, school size, and achievement and self-esteem among high school students: A national look. Journal of Research in Rural Education, 12(2), 92-103. Cotton, K. (1996). Affective and social benefits of small-scaled schooling. ERIC Digest. Dale, A., & Allen, J. (1995). The School Reform Handbook: How to improve your school. United States: Center of Education Reform. Deming, D. (2009). Early childhood intervention and life-cycle skill development: Evidence from head start. American Economic Journal, 1(3), 111-134 Friedkin, N. E., & Necochea, J. (1988). School system size and performance: A contingency perspective. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, 10(3), 237-249. doi:10.3102/01623737010003237 Gilbert, S. (1999). Supply chain benefits from advanced customer commitments. Journal of Operations Management, 18(1), 61-73. doi:10.1016/S0272-6963(99)00012-1 Gladden, R. (1998). The small school movement: A review of the literature. In M. Fine & J. I. Somerville (Authors), Small schools, big imaginations: A creative look at urban public (pp. 113-137). Chicago: Cross City Campaign for Urban School Reform. Goldenring, J.F., & Davis, J.M. (2003). Grade retention and enrollment in post-secondary education. Journal of School Psychology, 41(60), 401-411. Haller, E.J. (1992). High school size and student indiscipline: Another aspect of the school consolidation issue. Educatinal Evaluation and Policy Analysis, 14(2), 145-156. Heaviside, S., Rowand, C., Williams, C., & Farris, E. (1998). Violence and discipline problems in US public schools: 1996-1997. US Government Printing Office, Superintendent of Documents, Mail Stop: SSOP, Washington, DC. Howley, C. (1994). The academic effectiveness of small-scale schooling (an update). ERIC Digest. Kuziemko, I. (2006). Using shocks to school enrollment to estimate the effect of school size on student achievement. Economics of Education Review, 25(1), 63-75. doi:10.1016/j.econedurev.2004.10.003 Lamdin, D. J. (1995). Testing for the effect of school size on student achievement within a school district. Education Economics, 3(1), 33-42. doi:10.1080/09645299500000002 Lee, V. E., & Burkam, D. T. (2003). Dropping out of high school: The role of school organization and structure. American Educational Research Journal, 40(2), 353-393. 2015 JEPPA VOL.5, ISSUE 7 Lee, V. E., & Smith, J. B. (1997). High school size: Which works best and for whom? Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, 19(3), 205-227. doi:10.3102/01623737019003205 Lindahl, R. A., & Cain, P. M., Sr. (2012). A study of school size among Alabama's public high schools. International Journal of Education Policy & Leadership, 7(1), 1-27. Lowen, A., Haley, M. R., & Burnett, N. J. (2010). To Consolidate of not to consolidate, that is the question: Optimal school size and teacher incentive contracts. Academy of Educational Leadership Journal, 13(3), 1-14. Michelson, S. (1972). Equal school resource allocation. Journal of Human Resources, 7, 283306. Panzar, J.C., & Willig, R.D. (1977). Economies of scale in multi-output production. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 91, 481-493. Pittman, R. B., & Haughwout, P. (1987). Influence of high school size on dropout rate. Education Evaluation and Policy Analysis, 9(4), 337-343. Raywid, M. A. (1997). Small Schools: A reform that works. Educational Leadership, 55(4), 3439. Rumberger, R. W., & Thomas, S. L. (2000). The distribution of dropout and turnover rates among urban and suburban high schools. Sociology of Education, 73(1), 39-67. Rumberger, R. W. (1987). The impact of surplus schooling on productivity and earnings. Journal of Human Resources, 22(1), 24-50. Sanders, W. (1993). Expenditures and student achievement in Illinois. Journal of Public Economics, 52(3), 403-416. doi:10.1016/0047-2727(93)90043-S Smith, D., & DeYoung, A. (1988). Big school vs. small school: Conceptual, empirical, and political perspectives on the reemerging debate. Journal of Rural & Small Schools, 2(2), 2-11. Tanner, C. K., & West, D. (2011). Does school size effect students' academic outcomes. The ACEF Journal, 2(1), 17-40. Thornberry, T. P., Moore, M., & Christenson, R. L. (1985). The effect of dropping out of high school on subsequent criminal behavior. Criminology, 23(1), 3-18. Verstegen, D. A. (2011). Public education finance systems in the United States and funding policies for populations with special educational needs. Education Policy Analysis Archives, 19(21), 1-30. Viadero, D. (2001). Smaller is better: Studies show benefits of intimate settings but schools continue to grow. Education Week, 21(13), 28-29. 2015 JEPPA VOL.5, ISSUE 7 JEPPA www.jeppa.org The views expressed in this publication are not necessarily those of JEPPA’s Editorial Staff or Advisory Board. JEPPA is a free, open-access online journal. Copyright ©2015 (ISSN 2152-2804) Permission is hereby granted to copy any article provided that the Journal of Education Policy, Planning and Administration is credited and copies are not sold.