Home lessness BACKGROUND

advertisement

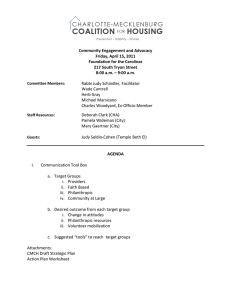

178-186 Homeslessness 12/29/11 2:25 AM Page 178 Home lessness BACKGROUND The plight of children, women, men, and families who are without residence continues to befuddle social workers in their recent ef forts, reaching back nearly three decades, to both serve people who are homeless and to find policy solutions. Indeed, scholars working in this area have suggested that the persistence of homelessness in the richest country in the world at the beginning of the 21st century is a consequence of massive policy failure (Stretch, 2004). Although sources disagree as to the exact strategies for determining the extent of the problem (Dworsky & Piliavin, 2002), on any given night, point prevalence estimates indicate that as many as 800,000 people are without shelter and are homeless in the United States. Furthermore, period prevalence estimates of the number of people who are homeless over a given year have been as high as 3.5 million (National Alliance to End Homelessness, 1999). Considerable literature has accumulated in social work and related professions covering a myriad of strategies for both better under standing and better serving people who are homeless (First Rife, & Toomey, 1999). Home lessness has been addressed broadly as a hous ing policy problem of largely political and eco nomic origins, and more narrowly it has been discussed as a mental health issue often related to deinstitutionalization. It has been studied as a domestic violence concern, a veterans issue, a disability issue, a welfare reform dilemma, a teenage runway or “throwaway” problem, and a transitional or temporary housing situation. It has been investigated as a migrant and immi grant problem, and a concern for people with communicable diseases. The problem for the consumer of this literature has been to decide exactly how a particular contribution fits into 178 SOCIAL WORK SPEAKS this vast pool of data, dimensions of practice, and policy recommendations. Fortunately, a variety of summary resources has recently be come available, both in the traditional published record (see for example, Levinson, 2004) and from more diffuse electronic sources (Table 1). No matter what the practice, policy or theo retical orientation of practitioners, researchers, and policy advocates, it is routinely recognized that the persistence of homelessness is evi dence that poverty and the lack of affordable housing in the United States still persist and are likely to remain critical policy issues for this next century. Homelessness is a complex problem that cannot be ameliorated until the shortcomings of past policies are recognized and the causes and consequences of persistent poverty combined with a lack of affordable housing are a matter of public record. The plight of people who are homeless must be bet ter understood from the perspectives of those who suffer, and it can be seen in 1. people with psychiatric disorders who lack the social networks, health care, and other program supports to live independently in the community (North, Fyrich, Pollio, & Spitz nagel, 2004; Wong, 2002); 2. individuals with physical disabilities, whose mobility limitations compound service inaccessibility (Pardeck & Rollinson, 2002); 3. women and children who are victims of domestic violence fleeing abusive domiciles (Bufkin & Bray, 1998; Danis, 2003); 4. asthmatic children in shelters who are not receiving adequate medical attention (Holden, Wade, Mitchell, Ewart, & Islam, 1998; McLean et al., 2004; Stretch & Kreuger, 1990); + 178-186 Homeslessness 12/29/11 2:25 AM Page 179 Table 1. Sources of Information on Homelessness in the United States Site URL National Coalition for the Homeless National Alliance to End Homelessness National Law Center on Homelessness & Poverty National Health Care for the Homeless Council National Coalition for Homeless Veterans National Low Income Housing Coalition National Resource Center on Homelessness and Mental Illness HUD Homelessness Website www.nationalhomeless.org www.endhomelessness.org www.nlchp.org/ www.nhchc.org/ www.nchv.org/ www.nlihc.org www.nrchmi.saml-isa.gov/ www.hud.gov/homeless/ 5. individuals currently employed either full- or part-time, with too little income to afford adequate housing (Hutchison, Searight, & Stretch, 1986; Johnson, 1999), or food (Big gerstaff, Morris, & Nichols-Casebolt, 2002); + 6. single mothers unable to work because of child care responsibilities or the lack of skills to meet the demands of a rapidly changing economy (Fogel, 1997; Johnson & Kreuger, 1989; North & Smith, 1993; Rivera, 2003); 7. runaway youths who are without access to adequate services (Baker, McKay, Lynn, Schlange, & Auville, 2003; Thompson, Safyer, & Pollio, 2001); 8. rural families who have been forced to abandon family farms or small towns due to economic crises in regional, national, and global markets (Coodfellow, 1999); 9. men, many of whom are veterans, who have only the life of the street for economic and social supports (Benda, 2002); 10. people with chemical dependencies, who are unable to maintain a stable residence (Bride & Real, 2003); 11. refugees, asylees, and migrants who have no place to turn to (Kobli, 2003); 12. individuals and families excluded be cause of their criminal history (Center for Law and Policy, 2003) 13. those displaced by disasters, whether natural, human-made or both (Zakour, 2000). Past and Prologue Throughout U.S. history policy on homelessness has tended to mirror societal responses to the conditions of the poorest of the poor popu lation. At the beginning of the 20th century, policy focused on either homeless men or dependent children in need of care. Men were often immigrants and lived in boarding houses during the winter months until seasonal jobs resumed. Those who were classified as tran sients were given aid through such practices as “passing on,” the forerunner to the “bus ther apy” of today (Menzies & Webster, 1987). Inter ventions by the Charity Organization Society, the settlement house movement, and faithbased groups focused on encouraging moral treatment for worthy poor people and work for unworthy poor people. During the Creat Depression, policy focused on families with children standing in soup lines and newly caught in the web of abject poverty. These new poor populations joined together with the transients and older beggars of the 1930s. Policy efforts were numerous and focused on structural causes rather than the personal deficits of poor people. In the 1950s the focus shifted to skid row, downtown areas populated by single adult men in cheap single room hotels. Policymak ing focused on the housing crisis through new construction and loan programs; however, after urban renewal, residents were displaced and when they could no longer pay rent, they turned to the only available temporary services HOMELESSNESS 179 + 178-1 86 Homeslessness 12/29111 2:25 AM Page 180 provided by organizations such as the Salva tion Army. From the mid-1960s to the early 1970s, the War on Poverty and the Great Society began to illuminate what had been a private problem and helped the nation to see that it required a public response. Welfare programs provided economic opportunity for poor people, but fed eral policy initiatives failed to give adequate attention to extreme poverty and the growing crisis in low-income housing (Blasi, 1994). The scope of the crisis in affordable housing was not well recognized or completely understood. It was generally assumed that homelessness had diminished or could be eliminated through other reform efforts. The Past 25 Years Beginning in the early 1980s, homelessness exploded as a social issue providing a sharp contrast to the values of opportunity for all. Before the public rediscovery of homelessness in the 1980s (Segal & Baumohl, 1980), it was widely assumed that homelessness was a social problem found either in Third World countries (now more accurately described as “dedevel oped nations,” Crotty [2001]), or in an earlier and less enlightened era in the United States. However, by the mid-1980s, rising housing costs, changes in labor markets, deinstitution alization of people with psychological or devel opmental disabilities (Bachrach, 1996; Fisk, Rowe, Laub, Calvocoressi, & DeMino, 2000; Segal & Baumhol, 1985), inadequate response to the needs of veterans, and related social forces cried out for greater response in the form of public policy. As this population grew, the estimated number of shelter accommodations rose from 275,000 beds in 1988 to almost 608,000 in 1996 (Blau & Abramovitz, 2004). As U.S. communities began to face the chal lenge of increasing numbers of people who were homeless in shelters or living in public spaces in the 1980s, research efforts in social work and related disciplines began to better document the nature and scope of the problem. Charitable organizations such as the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation funded health care for the homeless coalitions around the nation. Fundraising for these new public—private part180 SOCIAL WORK SPEAKS nerships and media focus increased national attention to homelessness as an ever-present problem. Debates about the numbers, charac teristics, causes, and consequences revolved around the definition of the problem as a per sonal crisis in the lives of individuals and fam ilies who were unable to afford housing or to benefit from job opportunities in the emerg ing postindustrial economy. Media coverage focused on the plight of people who were home less, and old myths about personal responsibil ity, worthy and unworthy poor people, and work continued to be perpetuated by conserv ative policy shapers and others as a part of the public debate. Advocacy groups were formed and focused on the need for affordable hous ing. Faith-based organizations set up commu nity kitchens and other services; missions, pub lic shelters, and local action groups grew in numbers and zeal. After passage of the Stewart B. McKinney Homeless Assistance Act of 1987 (P.L. 100-77), initiatives and grant-in-aid structures began to emerge. In addition to emergency shelter care, local efforts in service delivery began to include transitional housing, outreach, and case man agement, particularly to people with mental disabilities who were homeless. However, the crisis of homelessness continued to grow, par ticularly among people of color (Kreuger & Stretch, 1987), women with children; people living in overcrowded and poorly maintained housing, people with psychiatric disabilities (Segal, Silverman, & Temkin, 1995), and other families who were unable to close the gap between affordable housing and total family income (Stretch & Kreuger, 1989). Scholars such as Jahiel (1992) have identified a number of reasons for the growth of shelterbased services during the 1980s and 1990s, in cluding their obvious preferable value to sleep ing in harsh or dangerous conditions under bridges or in cardboard shacks. Shelters have been seen as providing emergency living quar ters for low-income families who suffer from loss of residence as a result of random and un predictable events such as fires and natural or human-made disasters. Critics have pointed out that shelters also developed partially in response to more predictable political or eco nomic pressures (Kreuger & Stretch, 1995). For + 178-186 Homeslessness 12129/11 2:25 AM Page 181 + example, condemnations that arose from the demolition of low-cost housing because of gen trification also contributed to the growth of shelters. All too often, affordable housing was replaced by shopping malls and entertainment complexes. Shelters offer safe haven for vic tims of domestic and street violence, ad they provide security as stopping off points for tran sients who otherwise would be stranded. Shel ters have been seen as a mechanism for ob taining access to improved housing through residential placement networks and public subsidies such as vouchers for Section 8 assis tance. Finally, shelters may provide alterna tive support for law enforcement officers who respond to requests from sometimes hostile city audiences to arrest people who are home less. Shelters provide care for people who real istically need a place to live rather than more extreme alternatives such as hospitalization or punitive incarceration. Evaluation studies have assessed both shorter-term outcomes (Glisson, Thyer, & Fischer, 2001) and longer-term effec tiveness (Stretch & Kreuger, 1993) of shelter services, with mixed conclusions. In 1994 the federal government published the first federal plan to break the cycle of homelessness, entitled Priority: Home! (U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Develop ment [HUD), 1994). The plan stated that “for the most part, homelessness relief efforts remain locked in an ‘emergency register” (p. 18). Homelessness is divided into two broad cate gories of problems: crisis poverty and chronic disability. The plan called for efforts to “rein vent the approach” because the “current ap proach is plainly not working and must be changed” (HUD, p. 4). A number of factors place people at risk of homelessness, including alcoholism; drug abuse; low education and illiteracy; sexual exploitation; chronic mental disability, developmental disabilities, or mild mental retardation; and HIV/AIDS. Our soci ety systematically and traditionally viewed those labeled as “worthy” poor people in these situations as “unworthy” poor people. On August 22, 1996, President Clinton ended “welfare as we know it” by signing the Per sonal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Reconciliation Act. This act ended the existing income maintenance system known as Aid to Families with Dependent Children, the Job Opportunities and Basic Skill Training Pro gram, and Emergency Assistance. These pro grams were replaced by the new federal block grant program known as Temporary Assis tance for Needy Families (TANF). Analysis by Sard (2001) of these changes in welfare spend ing indicates that some progress has been made in accommodating homelessness in TANF ad ministration. However, consistent cuts in pub lic expenditures for housing have been noted in the fact that HUD’s budget has decreased from approximately $85 billion in 1978 to just $29.4 billion in 2002, in inflation-adjusted terms (Blau & Abramovitz, 2004). Lessons from the Past After a century of shifting definitions of the problem, political denial, and policy neglect, the core of the homelessness problem clearly is extreme poverty and lack of affordable hous ing. Policies on homelessness, with only a few exceptions, have emphasized the alleviation of individual need and have underestimated the influence of systemic factors that would be sig nificant in reversing or preventing the underly ing conditions of homelessness (Jones & Crook, 2001). Past policy failures (Johnson, Kreuger, & Stretch, 1989) together with reductions in pub lic assistance, housing, health care, economic opportunity, education, nutrition, and affirma tive action do not offer much hope that society is capable of learning from either past mistakes or accomplishments. Too often policy-making processes at the federal, state, and local levels have been lim ited to local emergency measures, such as var ious health care for the homeless coalitions that began in the 1980s, rather than addressing the long-term structural and preventive dimensions of severe poverty and homelessness. Recurring themes of individual rather than communal responsibility and labels such as “bag ladies,” “panhandlers,” “handouts,” “hobos,” and “tran sients” have been the focus of public attention. Somewhat analogous to blaming each individ ual drop of rain for causing one to get wet, rather than responding to the larger weather system (structural foundations), policymakers have tended to rely on compartmentalized HOMELESSNESS 181 + 178-186 Homeslessness 12/29/1 I 2:25 AM Page 182 + solutions. Critics have pointed out that too often people who are homeless are substance dependent, illegal immigrants, or psychiatric outpatients, whose conditions would seem to justify narrower problem-focused solutions. But according to Blau and Abramovitz (2004), when homelessness is seen through the lens of an inadequate supply of affordable housing, who other than people in extreme situations are likely to be left after competition for scarce low-cost housing has run its course? However, valuable lessons are there to be learned. First, the scope of emergency mea sures during the Depression Era had a measur able effect in alleviating suffering and extreme poverty. Second, long-term structural mea sures such as social security and the indexing of these benefits, Medicare, and services to elderly citizens have been effective in protect ing some low-income older Americans from the risks of homelessness. Third, the failure to adequately respond to the needs of individuals who were homeless in the 1980s and 1990s led to an even greater crisis in the 21st century. The new chronic homelessness is recognized as a more multifaceted and entrenched problem than in earlier decades, one exacerbated by new at-risk populations, including those with communicable diseases. And far too often, communities have responded with more puni tive efforts to criminalize homelessness, rather than to work to prevent it (“Illegal to be home less,” 2003). ISSUE STATEMENT After three decades of disjointed efforts to address the crisis of homelessness in the United States, it remains a significant issue. The rea sons for this are primarily systemic, and home lessness and poverty are inextricably linked. Being poor means living on the verge of being an accident, an illness, a paycheck, a violent event, or a condemnation away from living on the streets. Being poor means having limited resources to cover the necessities of housing, nutrition, child care, health care, and education. Affordable housing, which absorbs a large pro portion of income for people who are poor, is too often abandoned when economic resources are insufficient to meet basic needs. The cost 182 SOC/AL WORK SPEAKS and difficulty of trying to find low-income housing once a domicile has been lost can pre sent tremendous obstacles, and cogent policies not supported by adequate resources exacer bate this problem. Studies indicate that whereas there were 6.5 million low-cost housing units for 6.2 million renters in 1970, by 1995 there were only 6.1 million low-cost units for 10.5 mil lion renters (Blau & Abramovitz, 2004). Policy making in relation to the problem of homelessness illustrates a drastic reshaping of the federal social welfare agenda in the United States during the past 25 years, but no single legislative answer has solved or significantly reduced homelessness (Burt, 2000). The dilemma of how to achieve this goal in a time of massive federal budget deficits, narrowly focused pol icy agendas, and the recent trend toward crim inalization of people who are homeless, merits our attention. In keeping with an empower ment perspective, social workers can and must join with people who are homeless to make sig nificant changes in their lives and in the social structures that surround them. POLICY STATEMENT To adequately address the problem of both shorter duration and chronic homelessness in the United States, policies should range from strengthening the capacities of the many peo ple who are homeless who are system victims, to changing social and economic conditions that foster extreme poverty and increase the risk of homelessness. NASW advocates the fol lowing as supportive and long-term solutions to the problem of homelessness: 1. The goal of an affordable and adequate home and a suitable living environment for everyone in the United States (Housing Act of 1949) should be vigorously pursued (HUD, 2004). 2. Social workers need to be actively in volved side by side with people who are home less (see, for example, Busch-Ceertsema, 2002) in national, state, and local coalitions to net work with and create advocacy groups; to identify significant problems in localities and create linkages to address and alleviate these + 178-1 86 Homeslessness 12/29/11 2:25 AM Page 183 problems; and to encourage state and local communities to use mainstream programs in building a continuum of care that integrates housing, income maintenance, and supportive services. 3. Federal, state, and local housing subsi dies should be available as an entitlement for all households with new emphasis on advo cacy for McKinney-Vento Homeless Assistance Programs; HOPWA (Housing Opportunities for Persons with AIDS); Section 811 for Persons with Disabilities; and programs for the Educa tion for Homeless Children and Youth (EHCY). 4. The complex patchwork of housing assistance programs (Mulroy & Ewalt, 1996) for low-income families should be organized into a more efficient and coordinated system that targets very poor people and households at highest risk of homelessness. 5. Efforts to encourage state and local com munities to use mainstream programs in build ing a continuum of care that integrates hous ing, income maintenance, and supportive services should be strengthened. 6. Education, job training, and related sup port services should be expanded to serve as key elements in the prevention of homelessness. Studies show that only 11 percent of peo ple who are homeless receive SSI benefits, whereas almost 40 percent experience mental health problems, and 46 percent report having at least one chronic health condition (Intera gency Council on Homelessness, 1999). 7. Homeless children need to be identified as a special population. They require proper nutrition, adequate clothing and hygiene, and continuous, appropriate education (including a space to study). Services to homeless children should be provided with an overall goal of stopping the cycle of homelessness, 8. Treatment and supportive services for special populations should be expanded and be focused on innovative approaches. 9. Federal, state, and local proposals to cut expenditures and restructure social welfare programs should be studied to determine their impact on homelessness. 10, The lack of bipartisan effort and consen sus on policy goals to end mass homelessness continues and is a major stumbling block to federal leadership in agenda setting and ap propriations. Political action strategies are needed to reverse this trend. 11. Support for a living wage to help pre vent homelessness should be widespread. Short-term program and policy changes are needed to cope with fiscal crises and the dis jointed community system of emergency ser vices for individuals and families who are homeless. Fiscal and programmatic recommen dations contained in new ventures, including the development of a National Housing Trust Fund and the Bringing America Home Act (www. bringingamericahome.org), merit our attention. State and local communities as well as nonprofit and public agencies should rethink the place of shelter care within a larger contin uum of services for special at-risk populations faced with crisis poverty and homelessness. Shelters have become an institutional response, but their presence should not be viewed as a policy solution (Kreuger, Stretch, Hodges, & Word, 2002). Social workers should be actively involved, in the company of people who are homeless, in the development of continuity of services for children and families. School social workers should work as advocates for the needs of children who are members of families who are homeless (Markward & Biros, 2001). Excessive rent and other housing burdens on poor people in urban and rural communities must be alleviated. State and local resources, including voluntary efforts, must be mobilized to develop creative solutions and stopgap mea sures for protecting people who are precari ously housed. Misconceptions about the causes of homelessness and severe poverty have con tributed to the lack of public support for efforts to alleviate homelessness. Social workers in partnership with elected officials and others must lead the fight in the interests of people who are homeless. The impact of homelessness on women and people of color in U.S. society is an important national issue and for the social work profession that must be translated into more effective efforts at coalition building. HOMELESSNESS I 63 t 178-I 86 Homeslessness 12/29/11 2:25 AM Page 184 Although more demands are being placed on shelters and emergency services to help people who are homeless, mainstream pro grams for housing assistance, public assis tance, and health care have been drastically cut to fund other political priorities. As programs are paralyzed by too many funding reductions, poverty becomes more severe and homelessness emerges as a growing and chronic reality for the poorest population. After three decades of disjointed efforts to address the crisis of homelessness in the United States, gaps in federal and state policies and inadequate funding are producing more homeless individuals. The impact of homelessness necessitates immediate action on the part of the social work profession. REFERENCES + Bachrach, L. (1996). Deinstitutionalization: Promises, problems and prospects. Jn J. Knudsen & C. Thomicrotf (Eds.), Mental health service evaluation (pp. 3—18). New York: Cambridge University Press. Baker, A., McKay, M., Lynn, C., Schlange, H., & Auville, A. (2003). Recidivism at a shelter for adolescents: First-time versus repeat runaways. Social Work Research, 27, 84—93. Benda, B. (2002). Test of a structural equation model of comorbidity among homeless and domiciled military veterans. Journal of Social Service Research, 29(1), 1—35. Biggerstaff, M., Morris, P., & Nichols-Casebolt, A. (2002). Living on the edge: Examination of people attending food pantries and soup kitchens. Social Work, 47, 267—277. Blasi, C. (1994). Ideological and political barri ers to understanding homelessness. Ameri can Behavioral Scientist, 37, 563—586. Blau, J., & Abramovitz, M. (2004). The dynamics of social welfare policy. New York: Oxford University Press. Bride, B., & Real, E. (2003). Project Assist: A modified therapeutic community for home less women living with HIV/AIDS and chemical dependency. Health & Social Work, 28, 166—168. The Bringing America Home Act, H.R. 2897, 108 Cong., 1st Sess. (2004). Retrieved July 184 SOCIAL WORK SPEAKS 20, 2004, from www.bringingamericahome .org Bufkin, J., & Bray, J. (1998). Domestic violence, criminal justice responses and homelessness: Finding the connection and address ing the problem. Journal of Social Distress and the Homeless, 7, 227—240. Burt, M. (2000). What will it take to end homelessness? Retrieved April 11, 2004, from www .urban.org/url.cfm?ID=310305 Busch-Ceertsema, V. (2002). When homeless people are allowed to decide by themselves. Rehousing homeless people in Cermany. European Journal of Social Work, 5(1), 5—19. Center for Law and Policy. (2003). One strike and you’re out: Low-income families barred from housing because of criminal records (fact sheet). Washington, DC: Center for Law and Policy. Crotty, R. (2001). When histories collide: The development and impact of individualistic capi talism. Walnut Creek, CA: AltaMira Press. Danis, F. (2003). The criminalization of domes tic violence: What social workers need to know. Social Work, 48, 237—246. Dworsky,A., & Piliavin, I. (2002). Homeless spell exits and returns: Substantive and method ological elaborations on recent studies. Social Service Review, 74, 193—213. First, R. J., Rife, J. C., & Toomey, B. C. (1999). Homeless families. In R. L. Edwards (Ed.in-Chief), Encyclopedia of social work (19th ed., Vol. 2, pp. 1330—1337). Washington, DC: NASW Press. Fisk, D., Rowe, M., Laub, D., Calvocoressi, L., & DeMino, K. (2000). Homeless persons with mental illness and their families: Emerging issues from clinical work. Paini lies in Society, 81, 351—359. Fogel, S. (1997). Moving along: An exploratory study of homeless women with children using a transitional housing program. Jour nal of Sociology and Social Welfare, 24(3), 113— 133. Clisson, C., Thyer, B., & Fischer, R. (2001). Serv ing the homeless: Evaluating the effective ness of homeless shelter services. Journal of Sociology and Social Welfare, 27(4), 89—97. Coodfellow, M. (1999). Rural homeless shelters: A comparative analysis. Journal of Social Distress and the Homeless, 8(1), 21—35. + 178-I 86 F-tomes?essness 12/29/Il 2:25 AM Page 185 + Holden, B,, Wade, S. L., Mitchell, H., Ewart, C., & Islam, S. (1998). Caretaker expectations and the management of pediatric asthma in the inner city: A scale development study. Social Work Research, 22, 51—59. Hutchison, W. J., Searight, P., & Stretch, J. J. (1986). Multidimensional networking: A response to the needs of homeless families. Social Work, 32, 427—430. Illegal to be homeless: The criminalization of homelessness in the United States. (2003, August). Washington, DC: National Coali tion for the Homeless and the National Law Center for Homelessness and Poverty. Interagency Council on Homelessness. (1999). Homelessness: Programs and the people they serve—Findings from a National Survey of Homeless Providers and Clients. Washington, DC: National Law Center for Homelessness and Poverty. Jahiel, R. (Ed.). (1992). Homelessness: A preven Hon-oriented approach. Baltimore: Johns Hop kins University Press. Johnson, A. (1999). Working and nonworking women: Onset of homelessness within the context of their lives. Affilia, 24, 42—77. Johnson, A., & Kreuger, L. (1989). Toward a bet ter understanding of homeless women [Briefly Stated]. Social Work, 34, 537—540. Johnson, A., Kreuger, L., & Stretch. J. (1989). A court-ordered consent decree for the home less: Process, conflict and control. Journal of Sociology and Social Welfare, 26(3), 29—42. Jones, J., & Crook, W. (2001). Homelessness and the social welfare system: The Briar Patch revisited? Journal of Family Social Work, 6(3), 35—51. Kohli, R. (2003). Child and family social work with asylum seekers and refugees. Child and Family Social Work, 8(3). Kreuger, L., & Stretch, J. (1987, June 7). Ethnic differentials among homeless families seeking shelter. Paper presented at the Minority Issues Conference of the National Associa tion of Social Workers, Washington, DC. Kreuger, L., & Stretch, J. (1995, April). Prevent ing homelessness: An empirical study of why shelter services don’t work. Paper presented at the annual meeting of the Society for Social Work and Research, Washington, DC. Kreuger, L., Stretch, J., Hodges, J., & Word, D. (2002). Are governmental policies solving the problem of homelessness? In C. Breme, H. Karger, & J. Midgley (Eds.), Controversial issues in social policy (Vol. 2, pp. 57—64). Boston: Allyn & Bacon. Levinson, D. (2004). Encyclopedia of homelessness (Vol. 2). Newbury Park, CA: Sage Publica tions. Markward, M., & Biros, E. (2001). McKinney revisited: Implications for school social work. Children & Schools, 23, 182—187. McLean, D., Bowen, S., Drezner, K., Rowe, R., Sherman, P., Schroeder, S., Redlener, K., & Redlener, 1. (2004). Undercounting and undertreating the underserved. Archives of Pediatric Adolescent Medicine, 158, 244—249. Menzies, R., & Webster, C. (1987). Where they go and what they do: The longitudinal careers of forensic patients in the medicole gal complex. Canadian Journal of Criminol ogy, 29, 275—293. Mulroy, F. A., & Ewalt, P. L. (1996). Affordable housing: A basic need and a social issue [Editorial]. Social Work, 41, 245—249. National Alliance to End Homelessness. (1999). Homeless ness: Programs and the people they serve—Findings of the National Survey of Homeless Assistance Providers and Clients [Highlights]. Washington, DC: Interagency Council on the Homeless. North, C., Fyrich, K., Pollio, D., & Spitznagel, F. (2004). Are rates of psychiatric disorders in the homeless population changing? Ameri can Journal of Public Health, 94, 103—108. North, C. S., & Smith, E. M. (1993). A compari son of homeless men and women: Different populations, different needs. Community Mental Health Journal, 29, 423—431. Pardeck, J., & Rollinson, P. (2002). An explo ration of violence among homeless women with emotional disabilities: Implications for practice and policy. Journal of Social Work in Disability and Rehabilitation, 2(4), 63—73. Rivera, L. (2003). Changing women: An ethno graphic study of homeless mothers and popular education. Journal of Sociology and Social Welfare, 30(2), 31—51. Sard, B. (2001, April). Using TANF funds for housing—related benefits to prevent homelessHOMELESSNESS 185 + 178-1 86 Homeslessness 12/29/li 2:25 AM Page 186 ness. Center on Budget and Policy Priori ties. Retrieved April 23, 2004, from http:// www.cbpp.org/4-3-01TANF.htm Segal, S. P., & Baumohl, J. (1980). Engaging the disengaged: Proposals on madness and vagrancy. Social Work, 25, 358—365. Segal, S., & Baumohl, J. (1985). The community living room. Social Casework, 66, 111—116. Segal, S., Silverman, C., & Temkin, T. (1995). Characteristics and service use of long-term members of self-help agencies for mental health clients. Psycluatric Services, 46, 269—. 274. Stewart B. McKinley Homeless Assistance Act of 1987, P.L. 100-77, 101 Stat. 482. Stretch, J. (2004, April). Opening plenary. Mis souri Association for Social Welfare Con ference on Homelessness, Jefferson City. Stretch, J., & Kreuger, L. (1989, August). Impact study on outcomes of services to homeless fain ilies: The results of a public—private partnership. Paper presented to the National Associa tion for Welfare Research and Statistics, Kalispell, MT. Stretch, J., & Kreuger, L. (1990). The twig is bent: An empirical study of homeless chil dren. Health Progress, 1(2), 14—19. Stretch, J., & Kreuger, L. (1993). Five-year cohort study of homeless families: A joint policy research venture. Journal of Sociology and Social Welfare, 19(1), 73—88. Thompson, S. J., Safyer, A. W., & Pollio., D. E. (2001). Differences and predictors of family reunification among subgroups of runaway youths using shelter services. Social Work Research, 25, 163—172. U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Devel opment. (1994). Priority home! (HUD-1454CPD[1J). Washington, DC: Author. Wong, Y. I. (2002). Tracking change in psycho logical distress among homeless adults: An examination of the effect of housing status. Health & Social Work, 27, 262—273. Zakour, M. J. (Ed.). (2000). Disaster and traumatic stress research and intervention: Tulane studies in social welfare. New Orleans: Tulane Uni versity Press. + Policy statement approved by f/ic NASW Delegate Assembly, August 2005. This policij supersedes the policy statement on Home less ness approved by the Delegate Assembly in 1996 and referred by tIme 2002 Delegate Assembly to the 2005 Delegate Assenthly for revision. For further information, contact (lie National Association of social Wom-kers, 750 First Street, NE, Suite 700, Washington, DC 20002-4241. Telephone: 202-408-8600 or 800-638-8799; e-mail: press@naswdc.org 186 SOCIAL WORK SPEAKS