BASIC COMPUTER LITERACY TRAINING TO INCREASE COMFORT LEVELS WITH COMPUTERS

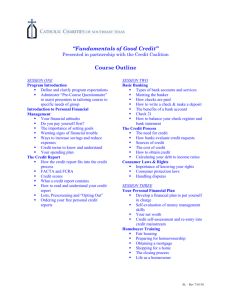

advertisement