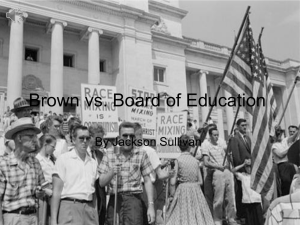

Fifty Years After the “Brown” Decision It is Time to... “What did the Civil Rights Movement Accomplish?”

advertisement