H A R T N E L L ... BOARD DEVELOPMENT DATE/TIME/PLACE

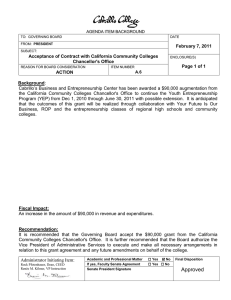

advertisement