Household Expenditure and the Income Tax Rebates of 2001

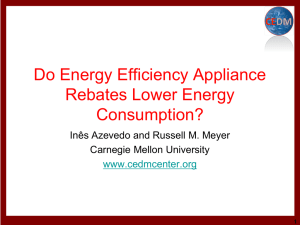

advertisement