eJournal of Tax Research 5

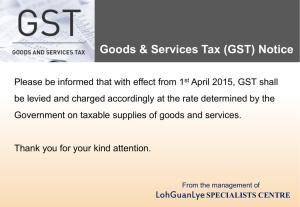

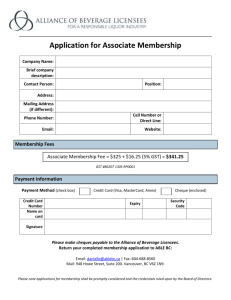

advertisement