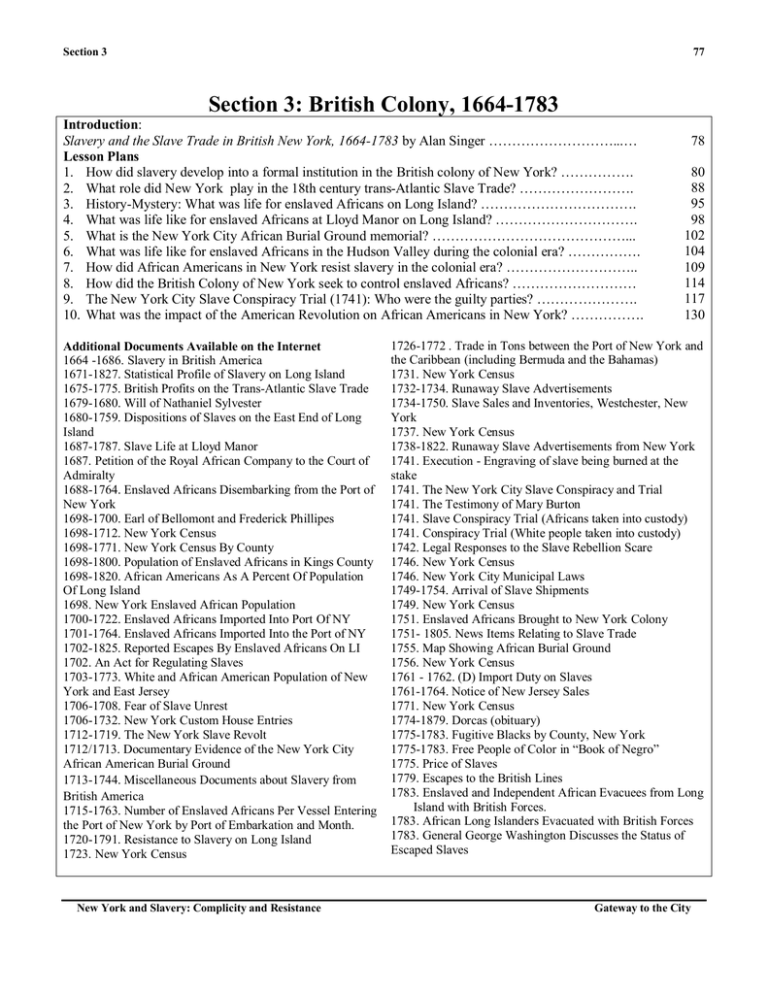

Section 3: British Colony, 1664-1783

advertisement