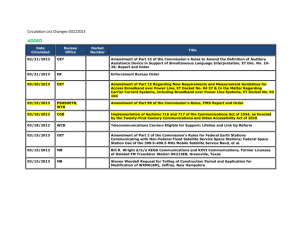

Social Science Docket

advertisement