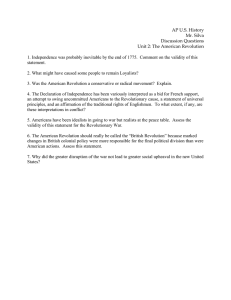

Social Science Docket

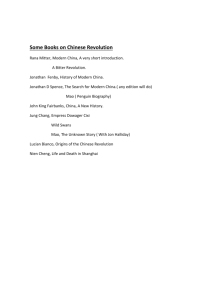

advertisement