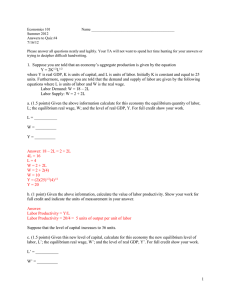

La Follette School of Public Affairs Current Account Balances,

advertisement