La Follette School of Public Affairs

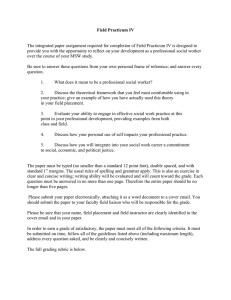

advertisement