Strategies for Total Quality in Radiation Therapy Introduction Sam Hancock

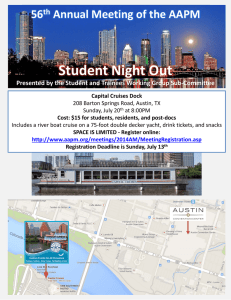

advertisement