April 2009 Nicholas J. G. Winter University of Virginia

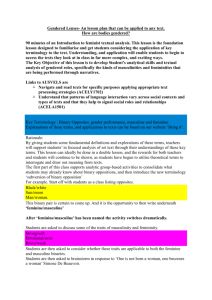

advertisement