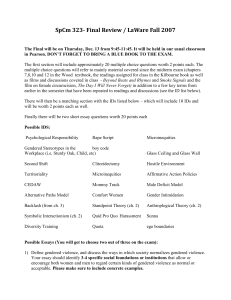

Masculine Republicans and Feminine Democrats: of the Political Parties

advertisement