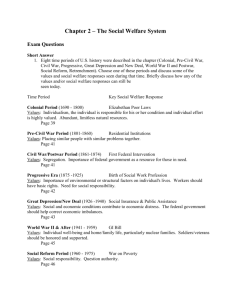

Perspectives on Social Work

advertisement