PERSPECTIVES ON SOCIAL WORK FALL 2015 VOLUME 11 ISSUE #2

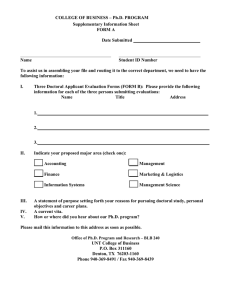

advertisement